Dani Gillespie was born and raised in China. Now she lives over 6,000 miles away, on Washington Island with her husband, island native Michael Gillespie.

They’re two of the 700 year-round residents who live on the island, which is about 4.5 miles off the northern tip of Door County. It’s one of the most remote places in Wisconsin, only accessible by ferry.

Over the years, Dani has discovered that living on Washington Island comes with some challenges. One big one? Connecting with her family back home.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“My internet freezes quite often and (my family members) were laughing at me” on video calls home, she said. “They said, ‘I thought you were living in America.’”

Michael Gillespie described his family’s internet service — which they also need for their two children to complete school assignments — as “spotty at best.” Sometimes, it takes hours for him to upload PDF documents needed for his job as a plumber.

And the family is not alone.

For years, many of the visitors and residents of the 35-square-mile island had to suffer through slow internet speeds and sometimes no internet service at all. But that’s all changing now, due to a $7 million, multi-year project to bring a new fiber optic network to every home and business on the island.

It’s part of a push happening across Wisconsin to connect those in sparsely populated areas with high-speed internet. That includes a $28 million project to connect thousands of rural residents and farmers in Richland, Dane, Iowa, Juneau and Sauk Counties to reliable internet, and an initiative to switch 1,500 Washington County residents from a slower DSL service to a high-speed service.

When the Washington Island project is over, the island will have some of the fastest speeds in Door County.

The need for high-speed internet access for rural communities across the state has been well documented. Ever since 2013, the Wisconsin Public Service Commission has worked to provide grants to expand access across the state through the broadband expansion grant program. But it could be several more years until their work is done.

A recent Federal Communications Commission report revealed that around 22 percent of rural residents in Wisconsin are living without access to adequate internet service.

To Robert Cornell, it doesn’t get any more rural than Washington Island. Cornell is the manager of the Washington Island Electric Cooperative and the driving force behind the project. He grew up on the island. He boasts that he graduated in the top 10 in his high school.

“We had 12 in my graduating class,” Cornell said with a chuckle.

On a sunny September day, Cornell drove his large black pickup truck from the ferry to the heart of the island. It’s a trip he’s made hundreds of times, and he enjoys reviewing the progress of the project.

“I can go down the road and say, ‘He has it, he has it, they have it, they have it, they have it. We’ve got them connected, and everybody on this road is connected,’” Cornell said about the project. “Very few people have turned it down.”

Across Wisconsin, there are still around 246,000 homes and businesses that lack access to internet speeds of 25/3 Mbps. That means a download speed of 25 megabits per second and an upload speed of 3 megabits per second, which is considered fast enough for basic video streaming.

There are an additional 217,000 locations that lack access to 100/20 Mbps, according to the Wisconsin Public Service Commission. That higher rate is more likely to support video calls, online games and other staples of internet use. This year the Federal Communications Commission has proposed setting 100/20 Mbps as the new minimum standard for broadband access.

Even though the state last year received $1 billion through the federal Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program, known as BEAD, Wisconsin Public Service Commission chair Rebecca Valcq said that after Republican state lawmakers denied a $750 million proposal from Gov. Tony Evers for expanding broadband access, it could be several more years until those homes get better internet access.

“We know it’s going to take more than the BEAD allocation to get everybody to 100 by 20 (Mbps) by 2030, but we are confident that we’re going to make incredible progress by 2030,” Valcq said.

Washington Island efforts to expand broadband began after a critical cable failed

On June 15, 2018, the 23,000-foot “submarine cable” that brings electricity from the mainland to Washington Island failed after several years of damage from ice shoves. The backup generators on the island quickly kicked in as leaders scrambled to fix the problem before the winter.

Officials decided to replace the old cable and in doing so, place a new fiber optic cable, complete with thin glass filaments, on the submarine cable that would bring the faster internet speeds to the island.

“The island had a few seconds of incredibly bad luck that we’ve now turned into a pretty good thing,” Cornell said.

Before the $7 million project began, many residents on the island only had internet access through DSL, or satellite signal providers like Starlink. Cornell said DSL service was unreliable and often up and down all day.

Joel Asher, network and telecom engineer for Quantum Technologies, also said Starlink became less reliable as time went on.

“As more and more people got on it (Starlink), the slower it became,” Asher said.

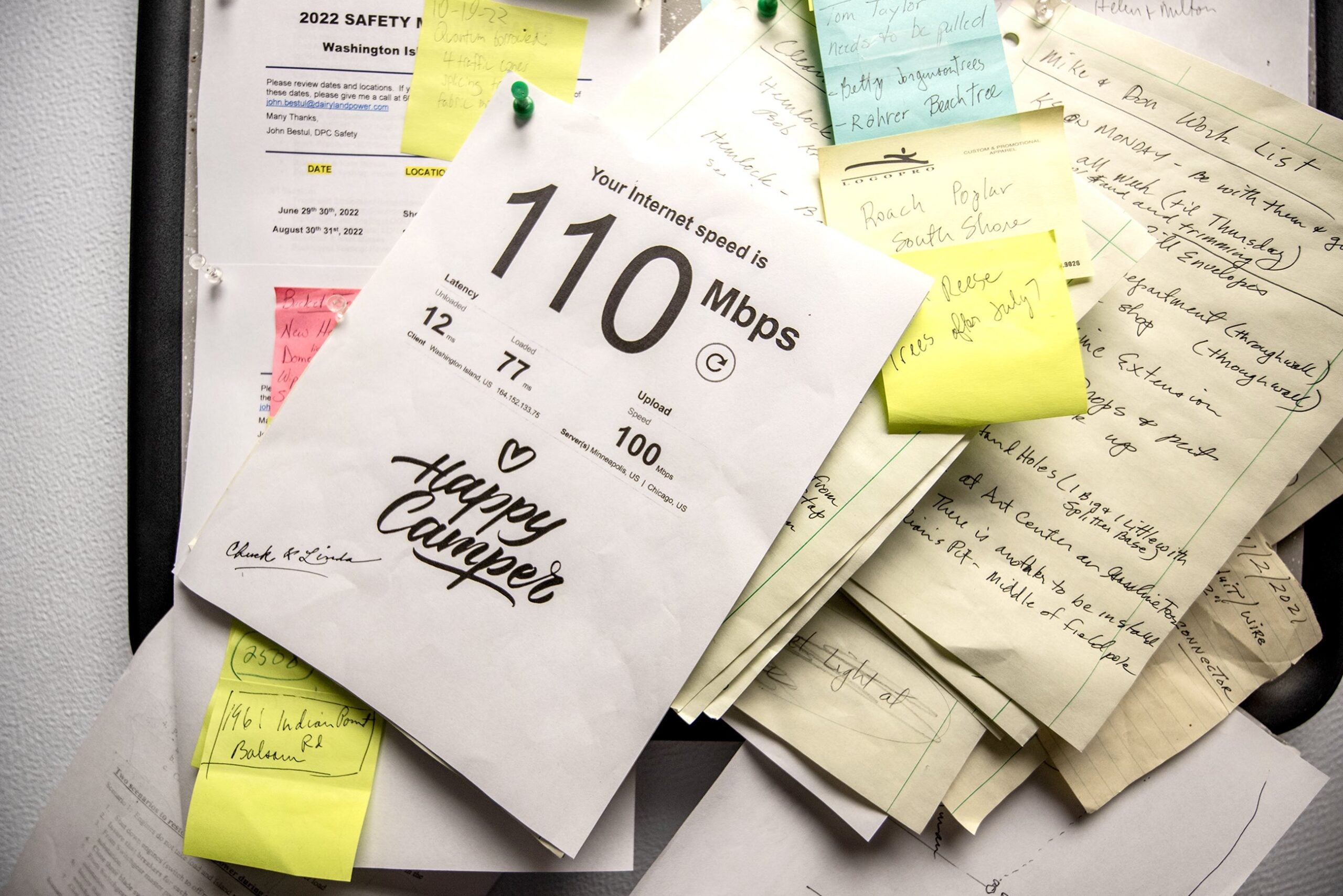

But the new service? Cornell said it’s a “night and day” difference.

In the last few years, private internet service providers have come and gone on the island.

“You’re only really served if you’re in control of your own destiny,” Cornell said.

For business owners Courtney and Eric Dejardin, who own the busy general store Mann’s Mercantile, the new service means more dollars in their pockets. The couple said their old service could be out for two to three days at a time. That’s a problem when a majority of their customers use credit cards.

“When you’ve got a business like this where you have mass customers walking in your door from open until close, and if you don’t have any internet service, you don’t have any money coming in,” Eric said.

The spotty service also threw a wrench in the operations of the Washington Island Ferry, which operates every day of the year — transporting people, mail, vehicles, cargo and essential supplies to and from the island.

Ferry director Hoyt Purinton, who is also a Washington Island Electric Cooperative board member, said the service would become oversaturated at times throughout the day. To him, internet data is as “important as cash flow.”

“If you don’t have it, you can be literally and figuratively dead in the water,” Purinton said.

Faster speeds come from fiber optic cable

With the new service, downloading a 2-hour long high definition movie takes around 38 seconds if you have a 1,000 megabyte per second fiber connection. With a cable connection, that would take nearly 7 minutes. A DSL connection could take nearly 30 minutes, according to Quantum Technologies.

The main difference is the material used to transmit data, as fiber optic cables use thin glass filaments, or fibers, to transmit data via high-frequency wavelengths of light. Cable and DSL internet use copper wire to transmit data, an older technology. Quantum said signal strength remains consistent regardless of distance with fiber, which isn’t the case for copper wire.

Simply put, copper wire has limited bandwidth.

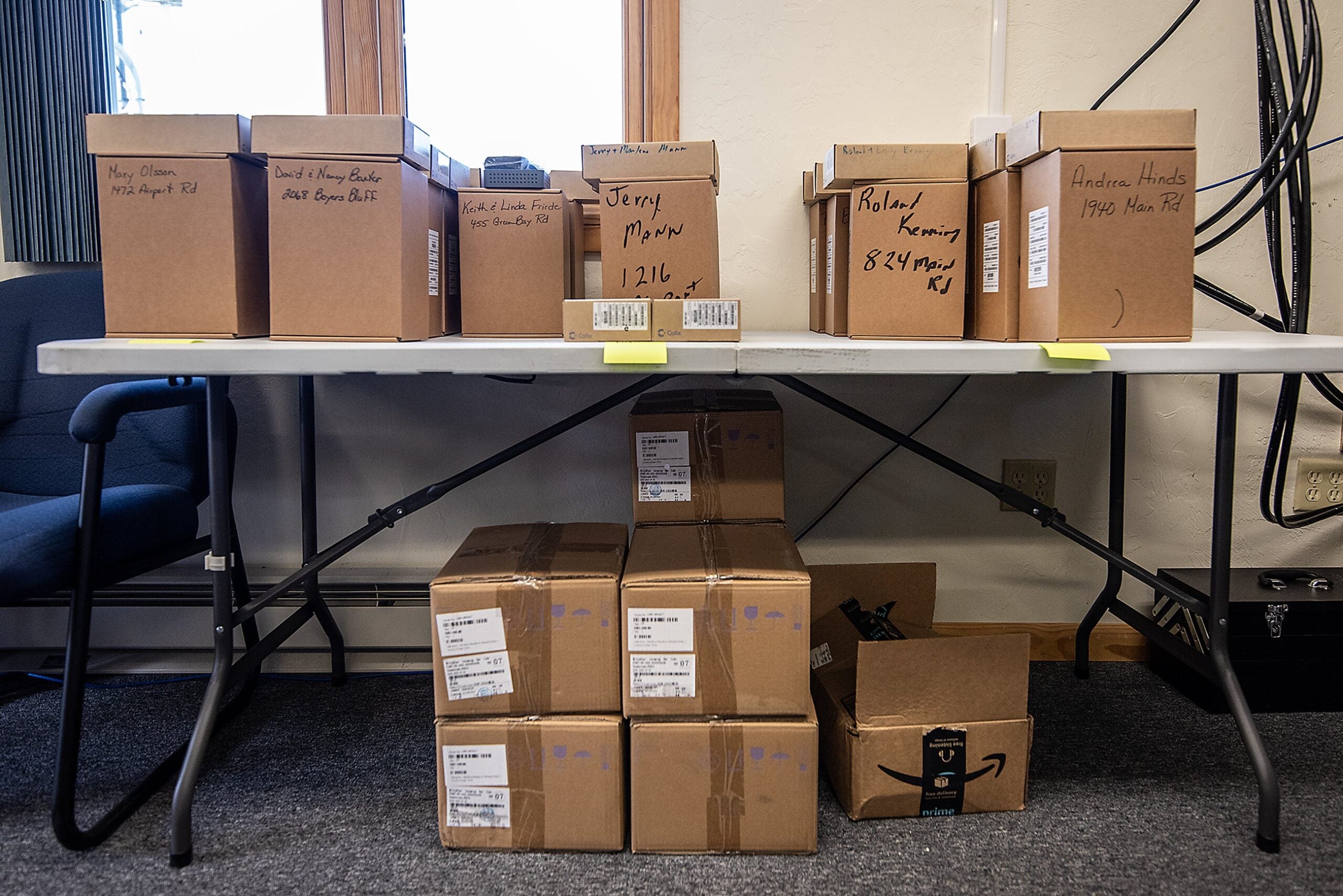

So far, more than 200 homes and locations across the island have the newer service. Cornell said the work began at “anchor institutions” on the island — including the school, police department, fire department and ferry office.

He expects around 80 to 90 percent of the island to get the service. It costs customers $59 a month for download speeds of 100 megabytes per second, while one gigabyte per second speeds costs $89 a month.

Around 50 percent of the project is being funded through grants while the Washington Island Electric Cooperative is paying for the rest. Cornell said the island received a $2.5 million grant from the Wisconsin Public Service Commission for the work. Because of that, Cornell said the island didn’t receive any of the BEAD program money.

“But that money is vital for the rest of rural Wisconsin,” Cornell said.

It’s not just island residents who are clamoring for faster speeds. Rural residents in all parts of the state also lack access to internet service that supports even low-resolution streaming video.

The Wisconsin Broadband Office estimates there are still around 650,000 residents without access to the infrastructure needed to bring 25/3 Mbps broadband into their homes or business.The state estimates another 650,000 people can’t afford broadband.

Brian and Renee Schaal own a 400-cow dairy farm in Burlington. They met with U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo in August, ahead of a visit from Vice President Kamala Harris. Simply put, Brian Schaal told Raimondo fast internet speeds are essential for his farm, as it relies on a radio frequency identification tag, or RFID tag, to help identify where cows are and which cow is which.

“But in order for that to work, we need the internet to upload that to the cloud and send it back every day,” Schaal said during the meeting.

The farm also relies on access to the internet for weather forecasts, which helps with crop management. But sometimes if the internet is spotty, he can’t even access an accurate forecast.

“So much of what we do is so weather-dependent, and when you have no service … you can’t see a forecast,” he said. “Sometimes, weather can shift and we can’t access the information.”

The Wisconsin Public Service Commission established its broadband office in 2009. Since 2013, the grant program has sent out around $300 million dollars to more than 400 projects across the state. When the grant period closes, a panel reviews applications and makes sure the project, which has to be a public-private partnership, is eligible for state funds. Valcq said the purpose of the grants is to fill in the gaps the private market left out.

The PSC estimates it would cost about $1.8 billion to bring higher broadband speeds to the entire state. Its leaders indicated that the state could have hit that benchmark with the federal funding and the state funds Evers proposed in his 2023-25 biennial budget.

But the rejection of the governor’s proposal was a blow to the work of the commission, Valcq said.

“We were very comfortable with saying that BEAD plus the governor’s proposal would have gotten everybody in Wisconsin to 100 by 2030,” Valcq said.

Now it’s unclear how long it could take to get everyone connected. Even so, Vaclq said she and the commission are working to procure more funds from the state in the coming years, to get the state “across the finish line.”

“The fact that the state broadband program does not have (state) funding as we sit here today leaves a little bit of uncertainty about where those additional dollars are going to come from,” Valcq said.

On top of that, there could also be additional hurdles in the coming years, as technology becomes more and more complex. Valcq said 25/3 Mbps speeds may have been able to do the job for many in the past, but the coronavirus pandemic demonstrated that speed wasn’t sufficient.

“As technology evolves, the need for future proof solutions to bring broadband to each and every home and business will only grow,” Valcq said.

Valcq also said fiber optic networks like the one on Washington Island may not always be the best solution for everyone.

“We have to be careful because as we sit right now, fiber isn’t a practical solution for some parts of our state,” Valcq said. “You can’t run fiber through a cranberry bog.”

For father and son Richard and Sean Clancy, the Washington Island broadband expansion project has brought them closer together. Sean moved from Chicago to the island to live with his father. The faster internet speeds mean he can work from home now.

“Now that they’ve got high speed, it means I can do everything,” Sean Clancy said. “Before, when you’re doing video conferencing and stuff like that, you’ll get the spinning wheel of death. Now you don’t get that.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.