With ice cover on the Great Lakes at a near-record low, the port of Duluth-Superior recently saw the latest departure of a cargo-carrying freighter in nearly 50 years.

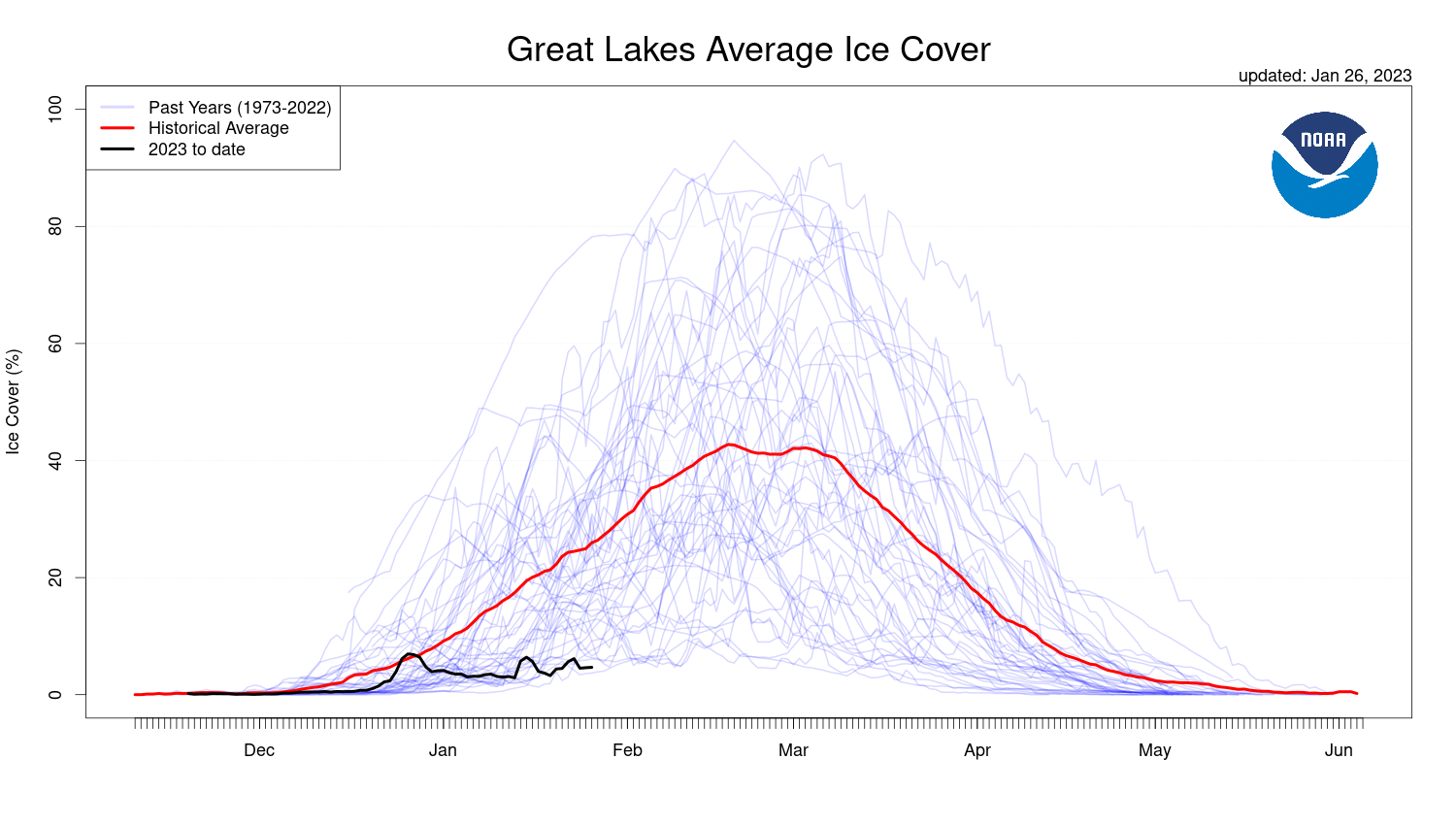

As of Thursday, ice covered only about 5 percent of the Great Lakes. This year is the fifth-lowest year for average ice cover on the lakes since the start of the season, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab. Through Jan. 25, the five years with the lowest ice at the start of the season have all taken place within the last two decades. The lowest average ice cover on the lakes for the start of the season was in 2021 at 1.4 percent.

With open water across the lakes, the lake freighter Saginaw left Superior at 4:20 p.m. on Jan. 21, with a load of iron ore cargo bound for the Algoma Steel facility in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The Duluth Seaway Port Authority said records indicate the shipment is the latest departure since Jan. 25, 1975.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“Late season shipments like this aren’t unprecedented, but they aren’t common either,” said Jayson Hron, the port authority’s spokesperson.

Shipments are rare after the Soo Locks close in mid-January, which typically signifies the end of the shipping season on the Great Lakes. The locks, which allow transit to the lower lakes, closed on Jan. 16 this year.

Hron said the late transit boosted the port’s iron ore shipments in January to roughly 970,000 tons, which is the largest for the month since the port authority began electronic record-keeping in 2003. Even so, the port ended the season with about 19 million tons of iron ore shipments — down about 2.3 percent from the five-season average. Overall, the port handled 30.4 million tons of cargo for the season, which is down 7 percent from the five-year average.

Researchers say the Great Lakes are seeing more years with very low ice coverage. Jay Austin, a professor with the Large Lakes Observatory at the University of Minnesota in Duluth, recently told Wisconsin Public Radio’s “Central Time” that the lakes had only one low-ice year from 1973 until 1998.

“Since 1998, we’ve had nine, and we’re on target for 10. (There is) very little ice-year this year,” Austin said. “And so, those sorts of events are becoming more and more common.”

The long-term average of maximum ice cover on the lakes each year since 1973 is roughly 53 percent, according to NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab. Data shows maximum ice cover on the Great Lakes is decreasing at a rate of about 5 percent each decade. Lake Superior has seen even greater ice loss at a rate of around 8 percent each decade.

Researchers have previously found climate change is causing lakes around the world to heat up faster than the oceans. A 2015 study by more than 60 scientists found ice-covered lakes like Lake Superior are warming more rapidly than those without ice cover.

“The Great Lakes are right at the top of the list as far as warming rates over the last 40 years,” Austin said.

Reduced ice cover prompted researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Superior to study how that may affect the shipping industry on the Great Lakes. Daniel Rust, associate professor of transportation and logistics management at UW-Superior, said a combination of ice loss and another lock at Sault Ste. Marie could mean a longer or even year-round shipping season.

“There was a period in the late ’70s, we had about five years of year-round operation of the Soo Locks and the upper Great Lakes didn’t shut down all winter,” Rust said. “That was during very cold winters, not in the era of climate change. So, it’s possible.”

Despite that, Rust said they found no direct effect between reduced ice cover and more cargo moving through the Soo Locks, which sees between 70 and 80 million tons of cargo each year.

“The market forces really dictate the volume of commodities traveling through the Soo,” Rust said.

With variation in ice cover each year, Rust noted that uncertainty is a major factor in whether the supply chain would shift to moving more commodities by water.

In Duluth-Superior, Hron said the port saw near or slightly above average shipments during low ice years in 2016 and 2017. Even so, the port topped 33.5 million tons in 2019 despite heavier ice on the lakes early that year.

“If there’s heavy ice at the beginning of the year, it might just mean that they have to pick up the pace a little bit when the ice clears,” Hron said.

While less lake ice may ease movement, UW-Superior researchers said that may only be true in the open lakes while harbors and ports may be more difficult to clear. In a warming scenario, Rust said they found there may be a need for more icebreakers due to the way ice moves and refreezes once it’s broken, which can make it more difficult to clear again. Congress recently authorized funding for another Great Lakes icebreaker.

Less lake ice means warmer water temperatures

Less ice on the lakes affects more than just shipping. Great Lakes researchers have found it also results in more lake-effect snow and increased wave activity.

Hilary Dugan, assistant professor at UW-Madison’s Center for Limnology, told WPR’s “Central Time” that lake ice and snow can also reduce the effects of light penetrating the water. That may make it easier for algal blooms to form.

“Less lake ice means different water temperatures, it means more sunlight, again, for photosynthesis, it means potentially stirring up nutrients from the bottom of the lake,” Dugan said. “So there’s lots of ways that ice could directly impact algae blooms.”

Dugan said less lake ice could also affect fish spawning because wind could stir up open water and disturb spawning in areas along the shoreline. That could stress species like whitefish in Lake Superior.

Meanwhile, Austin with the University of Minnesota in Duluth said less ice can lead to warmer water temperatures in the summer. In 2007, he and another researcher found that Lake Superior’s summer water temperature had increased by about 5 degrees Fahrenheit from 1979 to 2006.

Great Lakes researchers say projections vary on peak ice cover, but the lakes are expected to be at or below average maximum ice cover for the winter. James Kessler, physical scientist with NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab, said that could change.

“Right now, it’s still quite early in the season,” Kessler said.

Kessler noted peak ice cover typically doesn’t occur on the lakes until mid-February to early March. Last year, roughly a quarter of the lakes were covered in ice at this time, but ice cover peaked late on Lake Superior at about 80 percent in mid-March. Even so, Austin said the lakes are running out of time to form ice.

“It could still happen,” Austin said. “But, from the sort of medium- to long-term forecasts that I’ve seen, the likelihood of that is getting smaller and smaller over time.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.