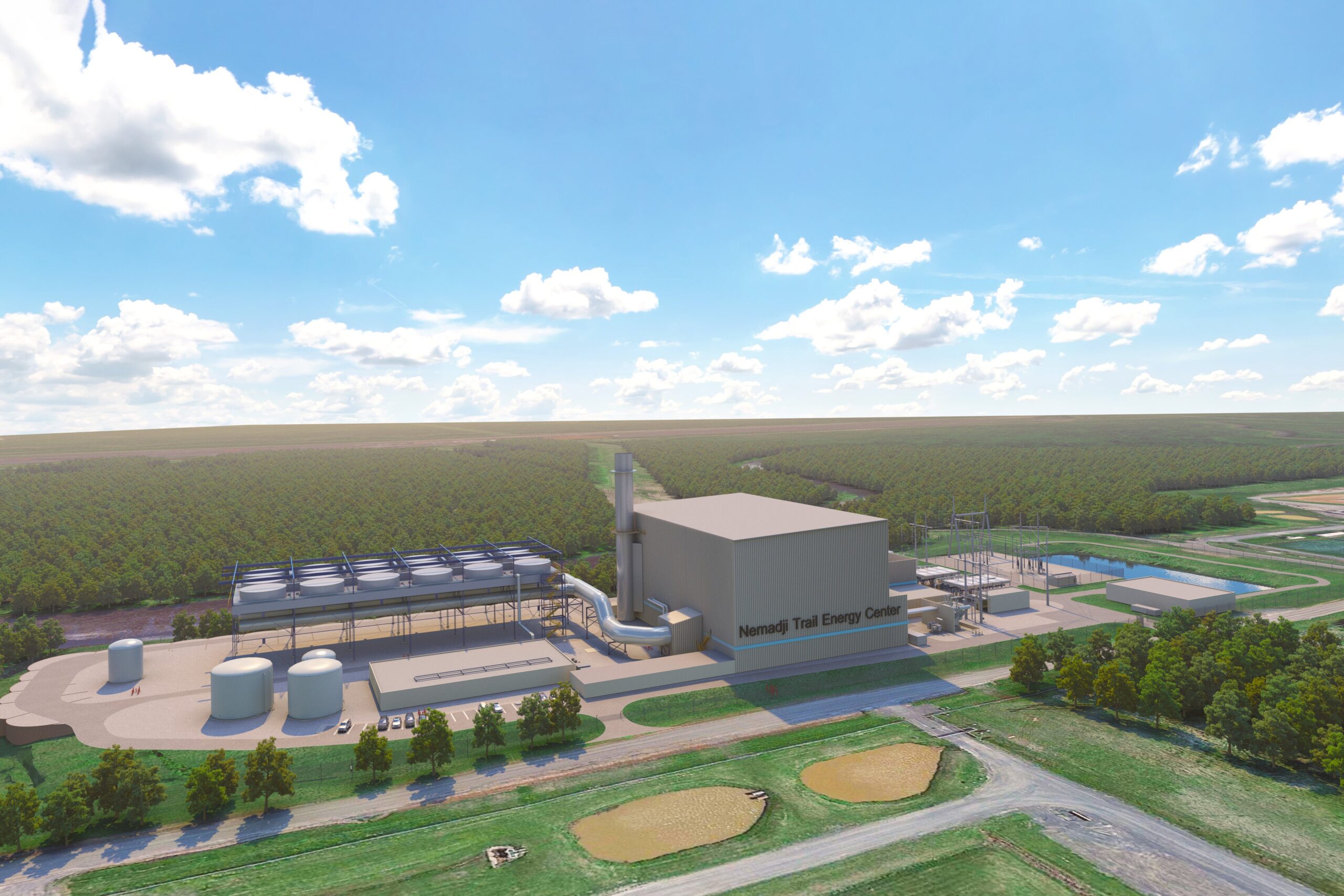

Utilities say a proposed 625-megawatt power plant in Superior will cut carbon emissions by about 1 million tons each year. But it will do so not by using renewable energy, but by burning natural gas.

That has made the proposed Nemadji Trail Energy Center the subject of a yearslong battle, as environmental groups and others have objected to utilities’ claims that natural gas remains a necessary part of the Midwest regional electric grid. The fight is an example of the complexity around the transition to clean energy. Utilities say fossil fuel-burning plants remain necessary because renewables like wind and solar energy aren’t always available to meet the demand for power.

But for many environmentalists, the creation of a massive new natural gas plant is a step backward.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Now, after years of debate, a federal agency is set to issue its finding on whether the project poses significant environmental effects as one of the plant’s owners seeks a loan to finance it. Utilities hope to finally break ground next spring, but environmental groups have already been calling for a more thorough review under a full environmental impact statement.

In September, a small group of residents gathered at the Superior Public Library to weigh in against the proposal as the Rural Utilities Service wraps up its latest environmental review of the plant. Residents like 23-year-old Kate Haga are worried about the project’s effects on climate change. The plant’s owners note natural gas produces half the carbon emissions of coal plants. But Haga highlighted that natural gas production releases methane, and those emissions have more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over the span of two decades.

“If they’re more potent, it’s going to just speed up climate change rather than do what it’s marketed to be, which is to be this bridge where we’re addressing climate change,” Haga said.

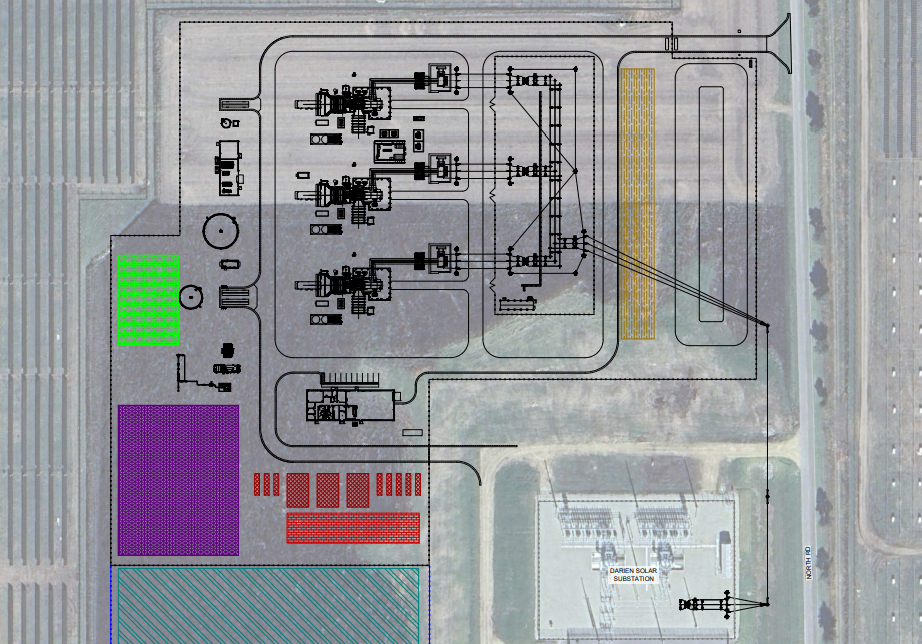

Utilities have been trying since 2017 to build the roughly $700 million natural gas plant in Superior. La Crosse-based Dairyland Power Cooperative, Duluth-based Minnesota Power, and North Dakota-based Basin Electric Cooperative would own the plant. Dairyland is seeking a loan from the Rural Utilities Service to pay for half the project’s cost.

Part of what has made the debate over the project so contentious is that environmentalists, regulators and the utilities do not agree on the underlying data that forms the utilities’ claims about the project’s environmental effects and whether it’s necessary to the electric grid.

In a setback for the utilities last year, the Environmental Protection Agency said the Rural Utilities Service failed to fully analyze the project’s effects on climate change. Federal environmental regulators say the agency’s review did not include estimates of greenhouse gas emissions associated with extracting gas and potential leaks. The EPA also found the plant’s projected 2.7 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions could bring around $2 billion in climate damages through 2040.

In its latest analysis, the Rural Utilities Service found the plant would still cut carbon emissions by 770,000 tons each year even with methane leaks compared to keeping coal plants online longer. The agency’s interim estimates show the project could bring $4.8 billion in climate damages through 2050, but the agency also said it would save around $2.2 billion by replacing dirtier coal plants on the regional grid.

But environmental groups contend the agency’s findings contain errors and relied on lower, outdated rates of methane leakage to gauge the plant’s emissions. They argue the project’s annual carbon emissions are closer to 3.4 million tons over the next century and 4.8 million tons over a 20-year span.

In comments on the revised analysis, EPA staff said it appears the Rural Utilities Service incorrectly calculated climate damages for the proposed plant, which the EPA estimated were around $2.8 billion. Federal environmental regulators also said staff couldn’t replicate the agency’s estimates on climate damages that would be avoided by building the facility.

Opponents like Haga point to scientists who say drastic cuts in emissions are necessary to keep temperatures from rising above 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) under the Paris climate accord. Haga said she would like to see more focus on renewable energy.

But the plant’s owners say there’s an increasing risk that the grid won’t meet demand for power as utilities retire coal and add wind and solar.

“A reliable natural gas facility helps ensure that we can maintain that reliability,” said John Carr, Dairyland’s vice president for strategic growth. “When wind and solar aren’t quite enough to meet demand, it’s there to ensure that that system is still reliable and affordable.”

Indigenous and environmental groups have mounted legal challenges in Minnesota and Wisconsin against utility regulators who approved the project. Courts in both states have upheld the regulators’ decisions thus far.

The Public Service Commission of Wisconsin declined to comment on the Superior gas plant, citing pending litigation. Even so, the commission’s energy regulation division administrator, Kristy Nieto, said it’s bound by laws enacted by the Republican-controlled Legislature when considering new projects. The commission weighs the need, costs, environmental effects and what’s technically feasible. Nieto said the existing fleet, including natural gas, will “play a critical role” in supporting renewable energy until technologies like battery storage are more readily available.

Activists say utilities need to move away from gas — not just coal

Technology around renewable energy is evolving daily, said Jadine Sonoda, campaign coordinator for Sierra Club Wisconsin. She and other advocates argue wind and solar could be paired with battery storage to meet demand. They’ve highlighted that other utilities in Wisconsin are doing just that.

“If we’re trying to invest in a clean future and a future that’s sustainable and healthy, especially for the local community, then we need to be only investing in this clean energy and not simultaneously investing in the gas plant,” Sonoda said.

She noted the Rural Utilities Service is providing billions of dollars for rural electric cooperatives to shift to clean energy under the roughly $370 billion Inflation Reduction Act. Dairyland Power has applied for federal funding from the agency to build 1,700 megawatts of new wind and solar at a dozen sites in Wisconsin, Iowa and North Dakota.

Even so, the cooperative maintains the Superior gas plant is key to their clean energy transition, saying challenges remain with the cost and duration of battery storage.

Scientists have said the world needs to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 to avoid the worst effects of climate change. Energy expert Greg Nemet, a public policy professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison, said any new natural gas plants would guarantee fossil fuel emissions beyond that date, or they would need to be shut down early.

“We’re going to be saddled with a lot of debt, and ratepayers are going to have to pay a lot for all these natural gas plants that we don’t use anymore,” Nemet said. “They’re going to have a pretty short lifetime.”

Dairyland Power said the plant would have a lifespan of at least 30 years, keeping it in operation beyond 2050. Even so, the cooperative maintains that building the Superior gas plant will help Wisconsin meet Gov. Tony Evers’ goal of carbon-free electricity by 2050. Utilities say they’re confident the plant could pivot to alternative fuels like hydrogen as soon as they’re commercially available.

Regional grid operator says projects like the Superior plant are needed

As federal regulators review the proposal, the operator of the Midwest regional grid said it supports projects like the Superior gas plant that can reliably meet demand. Last year, the Midcontinent Independent System Operator, or MISO, expressed concerns about an energy shortfall facing the region. MISO said it’s imperative resources that can dispatch energy when needed like the proposed Superior plant “be recognized for the regional reliability value provided to the region’s customers.”

This year, MISO said the region has adequate supply due in part to delayed plant closures, lower demand and more generation that was brought online in the last year.

Karen Clay, a professor of economics and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University, said natural gas plants are being built in part because of the rapid shift away from coal plants.

If a gas plant isn’t built, she said it could cost more to import natural gas from elsewhere. Beyond their goals to cut carbon emissions, utilities are also finding coal plants are more expensive to operate than renewables.

“The ones they plan to take offline are usually old and require maintenance and things like that, so that can be one issue,” Clay said. “Another issue is that at least some of these plants may be more highly polluting.”

Minnesota Power said it’s closed seven of its nine coal plants. It plans to shutter the last two by 2035, as well as add 700 megawatts of renewable energy.

“We have commitments to cease coal operations on our system. We have commitments to increase renewable energy and storage on our system. But those were all based on the premise that (the Superior gas plant) is coming online and providing really needed reliability support,” said Jennifer Cady, vice president of regulatory and legislative affairs for Minnesota Power.

Dairyland Power closed its Genoa coal plant in southwestern Wisconsin two years ago. The cooperative says it needs new capacity to replace recent retirements and meet growing demand. Superior Mayor Jim Paine is skeptical of Dairyland’s claims after the cooperative bought the 503-megawatt RockGen natural gas plant near Madison in 2021.

“With the acquisition of the RockGen plant outside of Madison, they are already exceeding their own projected demand,” Paine said.

Paine pointed to a filing with the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission that shows Dairyland’s forecasted load and capability would ensure there’s enough power to meet peak demand even without the Superior gas plant over the next 15 years.

Dairyland argued RockGen was acquired to ensure reliability when it retired its Genoa coal plant. The plant “has been serving the grid for 20 years — it is not a new resource,” Dairyland spokesperson Katie Thomson said in a statement.

As decision nears, some local leaders withdraw support

In addition to the debate about what role the plant would play in the transition to renewable energy, the project has also been the subject of more local concerns. Advocates say the massive construction project would fuel jobs and inject millions into the local economy. Meanwhile, some local leaders have withdrawn their support for the project over concerns that it’s placed too near to a burial site.

Utilities also say the new plant will bring a $1 billion economic impact over two decades and create 350 jobs during construction.

Kyle Bukovich, president of the Northern Wisconsin Building and Construction Trades Council, said it’s not a short-lived project for their members. The trade group signed a letter of intent to enter into a labor agreement with utilities in August.

“The estimated labor costs alone for this project is upwards of $300 million, and a vast portion of that will stay within the communities of Superior, Duluth and the surrounding areas,” Bukovich said. “It’s projects like this that put our members to work for a number of years of steady employment.”

In recent weeks, some city leaders in Superior have changed their position on the plant, saying they will oppose local permits for the project. They have voiced concerns with the plant’s contribution to noise and pollution.

They also highlight that the utilities’ preferred site is on the banks of the Nemadji River just hundreds of feet away from St. Francis and Nemadji cemeteries. More than 100 years ago, the remains of ancestors with the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa were buried in a mass grave at St. Francis Cemetery. That followed their removal from Wisconsin Point to make way for an ore dock that was never built.

Lake Superior Chippewa tribes, including Fond du Lac, urged federal regulators to examine the effects of the project on those graves, as well as climate effects on Indigenous populations. The Rural Utilities Service said in its most recent environmental review that no direct effects to tribes are anticipated, and the cemetery won’t be disturbed. In a subsequent letter, Red Cliff Tribal Vice Chair Rich Peterson wrote that the review failed to account for the fact the mass grave has already been eroded by the Nemadji River.

Jenny Van Sickle is a Superior City Council member and an Alaskan Native of Tlingit and Athabascan heritage. She pulled her support for the project, saying the site is a “nonstarter.” She said city leaders look back in horror at the removal of remains from Wisconsin Point.

“But in real time, we are seeing how clear-eyed, compassionate people can end up making decisions that can harm a community,” Van Sickle said.

Superior City Council member Mark Johnson said he’s also unhappy with the location, but he still supports the project. He acknowledged that Superior has had a sordid history with industry failing to be good stewards of the land.

“I would hope that in 2023, that time has passed and that the industries know better. When they know better, they do better,” Johnson said. “Where I see the past being concerning for some of these industries, I don’t necessarily feel like those same mistakes will be made again here.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.