A federal moratorium on evictions is set to expire Saturday, and that’s left many renters in Wisconsin wondering what comes next. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention instituted the moratorium in September, and it’s been extended four times since then. In the CDC’s most recent extension in June, the agency said in a statement it was “intended to be the final extension of the moratorium.”

WPR has received multiple questions about the moratorium and protections for renters through its WHYsconsin project. In a recent conversation on WPR’s “Central Time,” Kurt Paulsen, University of Wisconsin-Madison urban planning professor, spoke to host J. Carlisle Larsen about how the end of the moratorium will impact renters and landlords in the state.

What does the end of the moratorium mean for renters in Wisconsin?

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“There’s no way to sugarcoat it, it’s going to be bad,” said Paulsen. He explained that the eviction moratorium barred landlords from evicting tenants who were unable to pay their rent during the pandemic, but that renters are still ultimately on the hook for all the rent they missed when the moratorium expires.

“Thousands and thousands of renters have been unable to pay the rent because of unemployment or COVID-related financial hardships, and eventually the rent comes due,” Paulsen said.

After the moratorium expires Saturday, a wave of evictions could take place. Paulsen said in tight rental markets, some landlords may be less flexible with renters who are unable to cover rent with the expectation that they’d easily be able to find another renter to take their place.

But, he noted, many landlords don’t prefer eviction because it means they’ll lose rental income. In areas with weaker rental demand, landlords may be more willing to work out an agreement with their tenants on back-rent or reduced rent.

What assistance is out there if I’m struggling to pay rent?

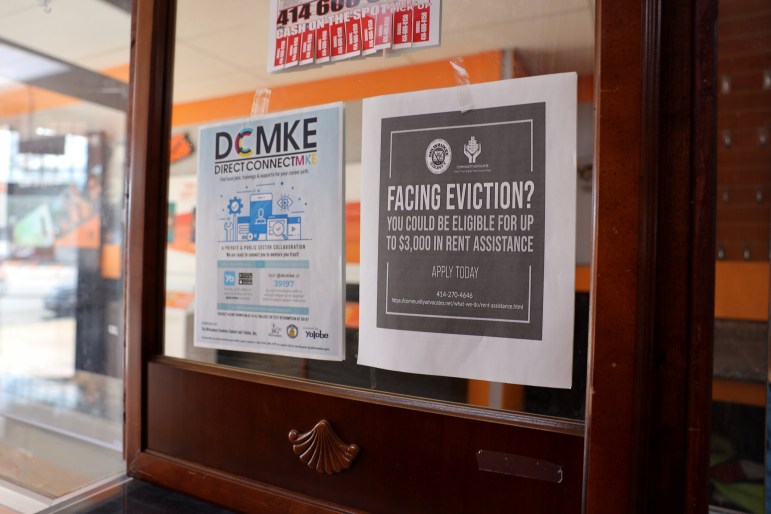

The good news, Paulsen said, is there are millions of dollars in emergency rental assistance available to help people unable to pay rent, including people who may not typically qualify for rental assistance.

That rental assistance can cover expenses like back-rent that may have piled up during the pandemic, utilities, moving costs, security deposits and rent going forward.

“People need to realize, you can get up to 12 months worth of rent — both back-rent and then future rent — if you are eligible,” Paulsen said. “So for many households that could be the difference between an eviction and homelessness, and being able to stay in their home or at the very least to kind of ‘clear the deck’ from the COVID-related loss.”

Information about signing up for rental assistance in Wisconsin can be found through the Wisconsin Community Action Program, a nonprofit that administers the program with the state Department of Administration. For a list of organizations by region that can help with rental assistance, see the bottom of this story or this map.

And, Paulsen said, tenants aren’t the only ones who can apply for the aid. Landlords are also allowed to apply on a tenant’s behalf.

But some who have applied for the aid have dealt with long wait times to get their applications processed, according to reporting by WPR and Wisconsin Watch, leaving some fearing they could be on the brink of homelessness as they wait for their aid to come through. Local aid groups involved in disbursing the aid have blamed the backlog on a large influx of inquiries about the program.

Are there other protections against evictions in Wisconsin?

The short answer is no, Paulsen said.

“There is no statewide eviction moratorium right now,” Paulsen said. “There was in the early days of the pandemic but that’s been overturned by the courts. And so the only real protection for renters to remain in their homes is the emergency rental assistance that is available.”

Paulsen also pointed out that many renters’ lease agreements have likely expired throughout the pandemic, meaning some are operating on month-to-month leases. For renters in that position, he said, landlords are under no obligation to renew that lease.

“There is no specific law that would protect a tenant who is unable to pay the rent after Saturday,” he said.

How much can a landlord increase rent?

There are no restrictions on the amount of rent a landlord can charge in Wisconsin, Paulsen said. He noted that that extends to the local-level as well, where counties, cities and towns are all prohibited from regulating rent.

“We say that the only thing that limits a landlord’s ability to raise the rent is the market itself,” Paulsen said. “Obviously if a landlord tries to raise the rent too high and tenants cannot afford to pay, they won’t get any tenants.”

But Paulsen points out that that can vary significantly depending on the quality and quantity or available rental housing stock where you live.

“We have areas of the state where rental markets are very tight — Madison, downtown Milwaukee, for example,” Paulsen said.

How does the eviction process work?

The only legal way a tenant can be evicted, Paulsen said, is when a court issues an order to the local sheriff to remove a person from their home. Paulsen laid out the process for an eviction as follows:

First — If a tenant is behind on the rent, the landlord would first have to give them a written notice that they are in violation of the lease. Generally this will be a five-day “cure notice,” which Paulsen said means that a person has five days to pay the rent (this notice can at times be a 14-day notice, depending on specific circumstances). If you pay the rent that’s owed within that five days, you have the right to stay, he said. Paulsen points out that, at this stage, the notice is simply a written notice from your landlord, not a court document.

Next — If the tenant has not paid the rent due within the five-day period, the landlord would file an eviction request in the small claims court of the local county circuit court. Following that, the renter is served with a notice telling them when to appear in court for their eviction hearing. Paulsen said, in between this period and the actual eviction hearing there are three things a tenant should do:

- Seek the help of a housing attorney (Paulsen recommends Legal Action of Wisconsin, or see this statewide list from Madison’s Tenant Resource Center)

- Apply for emergency rental assistance (see “What assistance is out there if I’m struggling to pay rent?” section above for details on how to apply)

- Document everything you do and get everything related to the eviction in writing

After that — A court hearing for an eviction generally happens about 25 days after a landlord files an eviction petition. Paulsen cautions that the courts will likely be backlogged with eviction cases, and it’s not clear how long that backlog will be. But, he said, if a tenant doesn’t show up for their court date, they are evicted. If the tenant does appear in court, it is only at the end of the hearing that a judge can issue a “writ of restitution,” which is an order to the sheriff to remove you from the home.

Where can I rent after being evicted?

Paulsen notes that once a renter has been evicted, that eviction stays on their record between two and 10 years. For that reason, renting with an eviction on your record can be a challenge. Paulsen said landlords might be less likely to rent to you, you may experience limits on where you can rent, or you may have to pay more for a lower-quality home.

Local housing nonprofits in your area may be able to provide some options for places that will rent to people with a past eviction. The list of local organizations doling out emergency rental assistance around the state is a good starting place, but other rental advocacy organizations exist on the local level, like Madison’s Tenant Resource Center.

Paulsen stressed that the best thing a renter can do is avoid an eviction by applying for emergency rental assistance, getting advice from a housing attorney and working out an agreement with your landlord.

“You can negotiate a deal with your landlord — maybe a payment plan, maybe a partial payment plan — and maybe you still move out, but that’s not an eviction, and it’s not going to show up on your record.”