If you’re driving north along Highway 53 between Spooner and Trego, you’ll see a long line of railcars parked on tracks on your right. The string of railcars seems like it will never end.

Some have graffiti and look weathered. Others appear new. Some railcars are round and others look like a box.

Mary Kay Lovejoy passes these railcars on the way to her cabin in Bayfield County. And she has always wondered why they’re parked here.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I always wondered, do these move? Are they just here in storage? And then I got curious, well, are they related to the frac sand mining? Why are they there all the time?” she said.

Lovejoy tried to answer her questions on her own.

“Sometimes I would try to pick out an identifying characteristic of a car, like a number or some graffiti that was painted on it. And I’d think, ‘OK, next time I come by, I’m going to remember that and see if it’s the same cars or if it’s different cars,’” she said. “But, of course, then I would never write down what I picked out so then I couldn’t remember.”

The mystery prompted her to ask Wisconsin Public Radio’s WHYsconsin for help.

Most of the railcars parked for miles and miles in Trego are used to haul frac sand and have been sitting for one to three years.

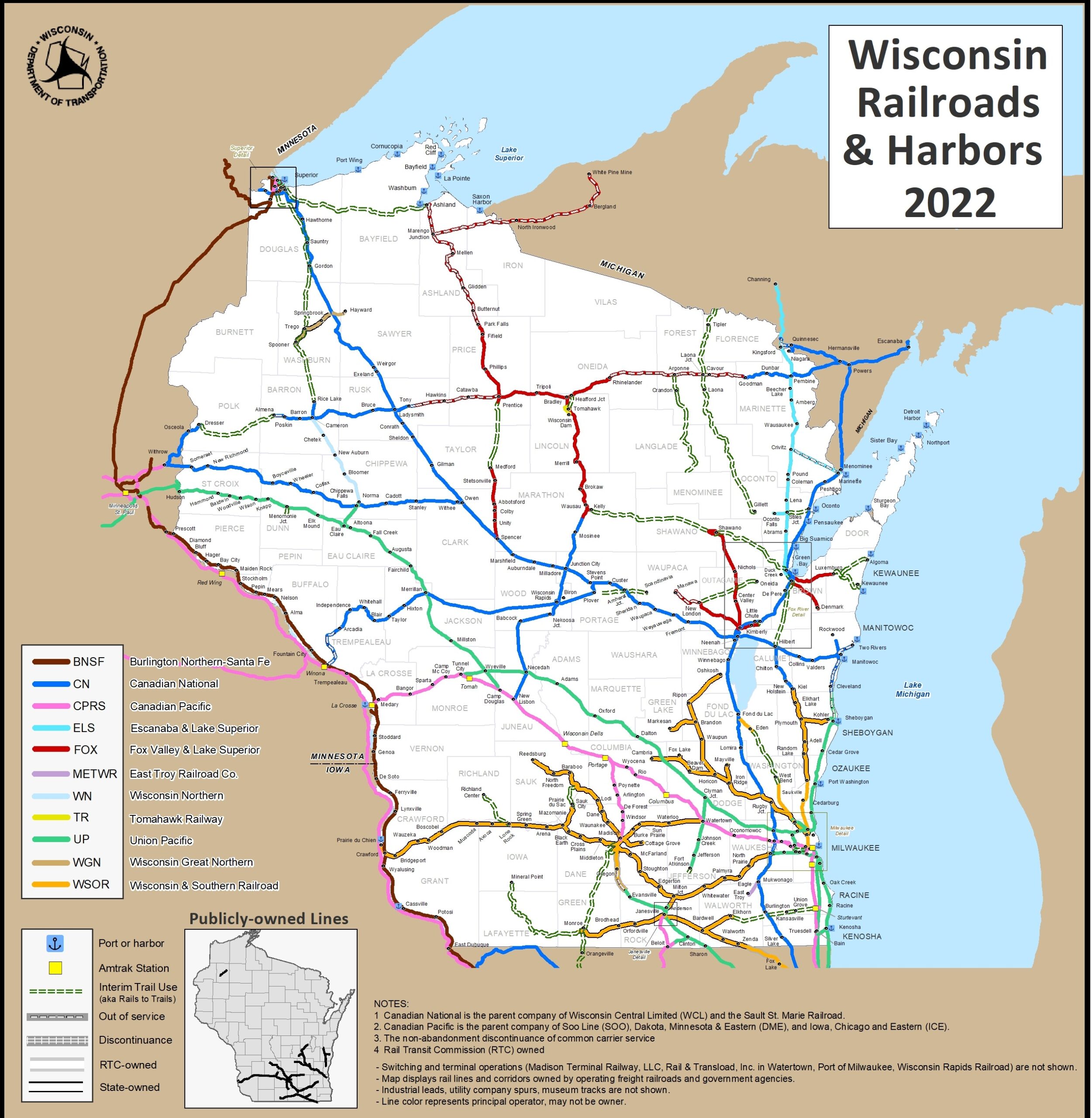

That’s according to Greg Vreeland, general manager of the Wisconsin Great Northern Railroad, a company that operates on the tracks where the mysterious railcars are parked.

Vreeland said a couple things determine if a railcar is moving from place to place: the global economy and markets and what commodities are in demand.

“At various points of the year, railroad cars of specific types become surplus to the needs of the shipping community and when there are extra cars that need a place to park, the railroads and the owners of the cars work with the small, what they call shortline railroads, to use extra pieces of track that are not being used for another purpose to store the cars on,” he said.

Vreeland leases 26 miles of tracks from the state of Wisconsin and Canadian National Railway. Some of the rail is used for his business’ scenic train rides. The railcars Lovejoy was curious about? They are parked on another portion of these leased tracks.

Vreeland said there are close to 500 railcars from various companies around the world parked on a six-mile portion of the tracks.

“The frac sand market is currently depressed,” Vreeland said. “So there’s not the need for the number of cars that there was a few years ago. So consequently, there are a few hundred frac sand cars currently parked.”

Railcars are expensive to build, and their lifespan is decades long. When they aren’t being used they are parked somewhere because it’s more economical to store them until they’re needed rather than scrap them.

“If everything is right in the world, they won’t sit at all,” Vreeland said. “They’ll have just the amount of cars that they need for the business that’s available. But there are these fluctuations in the market. There are just certain times (of) the year when certain cars need to be parked. Oftentimes that’s only for one or two months, and then they’ll be right back to being used. But occasionally, like with this frac sand downturn, there will be a situation where there’s just too many cars and some of them need to be parked for a long period of time.”

Companies try to place railcars near where they’ll be used, but Vreeland said storage can be hard to find when there’s an economic downturn. Vreeland has a car all the way from Mexico. It hauls sand and landed on his tracks 18 months ago.

“When we have a recession or a downturn, a lot of cars need to be stored,” he said. “Unfortunately, storage becomes very, very short supply and then cars, wherever they can find a place, they get stuck. Oftentimes it’s a thousand miles away from where they’re going to be needed, but that’s all they could find the day they needed to store them.”

The economy also drives how often a railcar is pulled from the string.

“You can go for a year without getting a call and then get six calls in a week,” he said.

“It’s so related to the global financial (market), it’s so far beyond northern Wisconsin. It’s a big-time-world-event kind of thing. You know, they decide … they’re going to open up the drilling in North America again and frac sand could be really big two months from now. You just never know. And if that happens, I mean, the phone will just ring off the hook. It’s like, ‘We need our cars back. We need our cars back.’ And then you’re moving about as quickly as you can possibly move about. And then six months later, the same cars might be coming back again. You just don’t know.”

During the 2008 financial crisis and later housing market fallout, tens of thousands of railcars were parked on upwards of 80 miles of tracks in Montana and hundreds were parked in Washington state.

When Vreeland’s staff does pull a car, it can be time consuming. He said if a railcar is deep within the 500-car string, an engine is used to pull cars out — about 80 at a time — until the car called up for use is reached.

For now, the railcars will sit here, waiting for the day they’re needed to move goods from place to place.

This story was inspired by a question shared with WHYsconsin. Submit your question below or at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it.