When schools shut down in the spring of 2020 and most districts switched to virtual learning, families quickly learned that there was a difference between having internet access and having internet that was strong enough to support learning online.

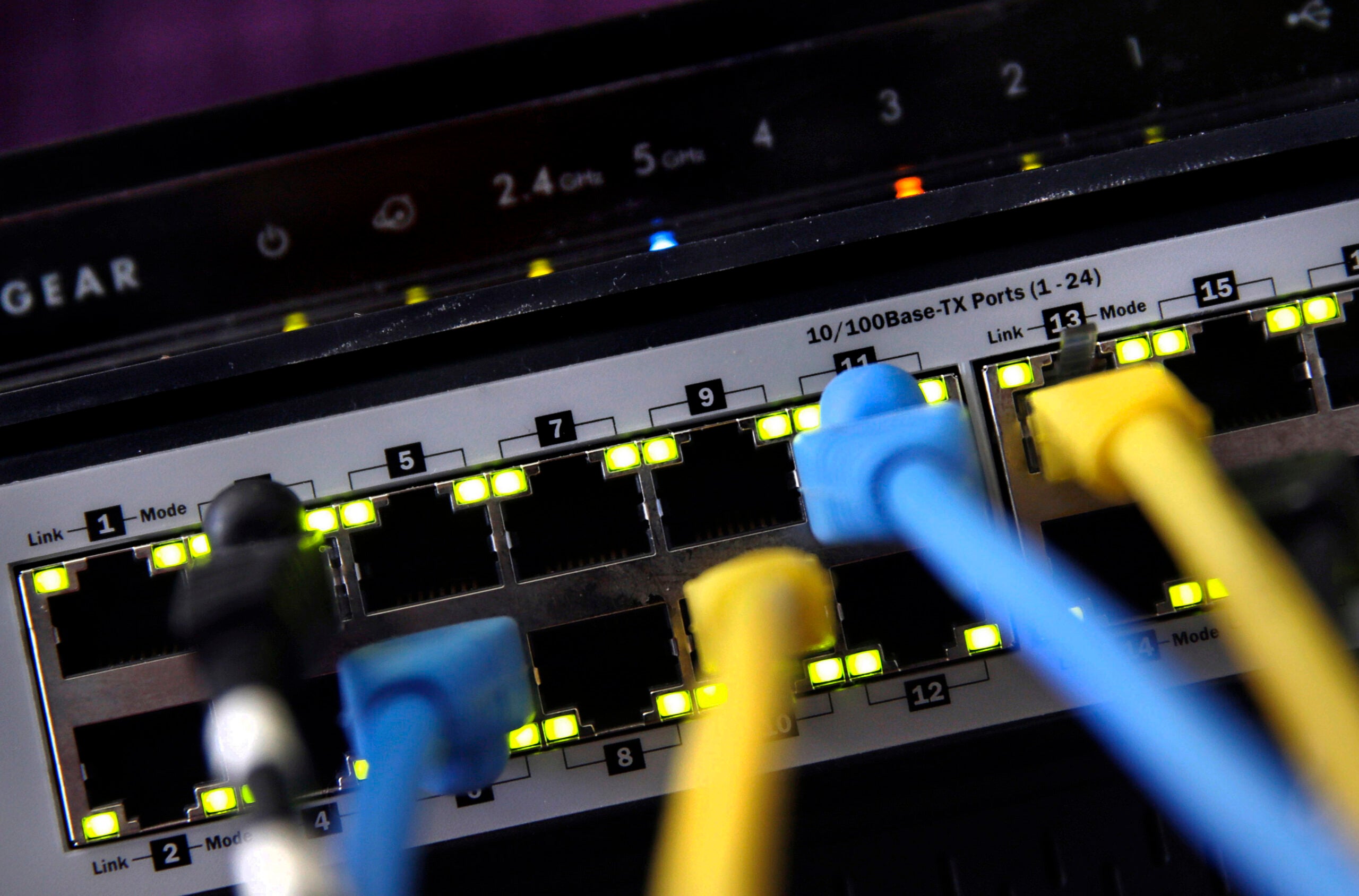

Although the Federal Communications Commission defines broadband access as having 25 megabits per second in download speeds and 3 megabits per second in upload speeds, when students were signing in to video lessons through Zoom or Google Classroom, that upload speed wasn’t cutting it — especially if multiple siblings were Zooming at once, or a parent was also trying to work from home.

Kurt Kiefer, assistant superintendent in the division of libraries and technology at the state Department of Public Instruction, said school districts were able to quickly bring the percentage of students with no broadband access at home down from about 15 percent in the fall of 2019 to less than 5 percent by the start of this school year, mostly through school-issued internet hotspots and directing lower-income families toward free internet packages from internet service providers.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Then DPI started asking families if they could stream a video for learning purposes on their student’s primary learning device — whether that was a Chromebook, a phone, an iPad or something similar. They found that about 25 percent of families couldn’t reliably do so.

“There’s about 30,000 students whose parents are saying, ‘Nope, flat-out nope, I can’t do it,’” Kiefer said. “And then another probably 160,000 to 165,000 saying, ‘Yeah, but it’s not consistent in any way.’”

Between January and May, DPI had families run speed tests of their home internet, and mapped their upload and download speeds.

That gap between simple broadband access and adequate broadband speed to learn from home became quickly apparent to Mark Holzman, superintendent of the Manitowoc School District. Manitowoc students had Chromebooks early on — students in grades six and up had already been issued their own devices, and the district was able to get devices from school buildings to its students in grades first through fifth.

“We learned pretty quickly that what we thought was Wi-Fi, or was robust Wi-Fi in our homes, was not, especially when we had multiple people trying to access the same site,” he said. “Parents used to using their phone as a hotspot were not going to handle the bandwidth of virtual learning.”

Manitowoc, like districts all around the state, started buying up portable Wi-Fi hotspots as quickly as they became available and distributed them to families who didn’t have strong broadband at home.

Statewide, Kiefer said about 13,000 to 15,000 students are currently using a cellular hotspot provided by their school district.

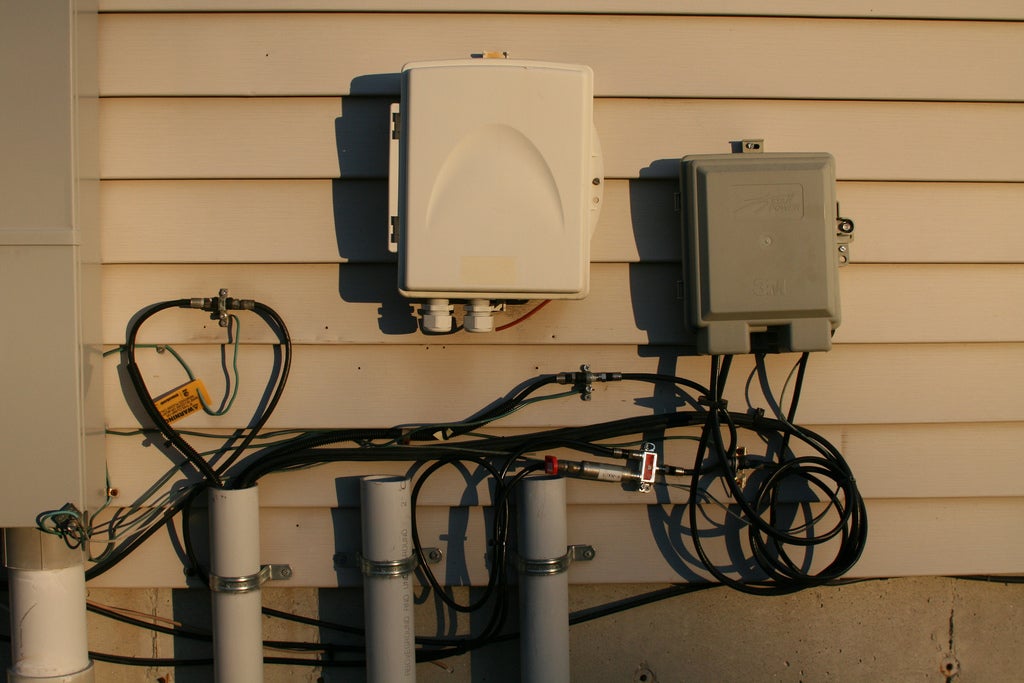

In Northland Pines, a rural district in northern Wisconsin that covers a large geographic area, cellular hotspots could only get students so far.

“Unfortunately, a lot of our area up here, not only do we lack broadband, we lack cell service,” said Northland Pines Superintendent Scott Foster. “So that isn’t some end-all, be-all solution, either.”

Northland Pines offered in-person instruction five days a week starting in the fall, in part because it was the only way to reliably reach all of its students. Foster said about 10-15 percent of the district’s families don’t have any cell or internet service, and about 60 to 75 percent could use a higher quality, more reliable internet option.

Foster said the district, the county, local businesses and state agencies have been working to build out fiber internet in the district. They’ve also been in talks to send up a drone that would supply Wi-Fi to the area.

“We also found that there are some that have access, but don’t have the financial means,” said Foster. “It’s kind of a multi-spur approach — you have to assist families to help get it, then to have it, you have to make sure they can afford it, and then the creativity comes in, like the drone.”

Paul Fischer, superintendent of the western Wisconsin Alma Center-Humbird-Merillan district, has been working with the county government to put out requests for information from local service providers, and write grant proposals for state-level broadband funding programs.

“Statewide, we keep hearing about broadband expansion, and all these millions of dollars put into it, but what you don’t realize, and what I learned very quickly, is it’s so much more than this magical snap your fingers and there it is,” he said. “There’s so much that has to be done just to get these areas so that they can receive service.”

In a survey of his district, Fischer said about 87 percent of students were experiencing some kind of interruptions in their internet service.

Despite all the barriers, including multi-thousand-dollar price tags to lay fiber cables far enough to reach some families in rural areas, Fischer said it’s been easy to find partners within the county who want to get involved — in part because they see how better internet access helps not only students, but also could help people working from home and even make it easier for law enforcement and emergency services to respond to people currently living in cellular or internet dead zones.

“This pandemic, if it’s taught us one thing, is that working from home or remotely is going to be much increased over the years,” he said. “We just have to have that access and availability of internet to make it work properly.”

Kiefer, at DPI, said the families who still don’t have internet access are fairly evenly split between families who don’t have access, and families who can’t afford internet. Still, he’s optimistic that Wisconsin can close the remaining gap of families with no or inadequate internet.

“We did this almost a hundred years ago, with electricity,” he said. “We can do it again.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.