Wisconsin environmental regulators can once again move forward with setting health-based standards for PFAS in groundwater — a source of drinking water for one third of state residents who rely on private wells.

The Wisconsin Natural Resources Board voted unanimously Wednesday to allow the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to begin crafting regulations for the so-called forever chemicals in groundwater. The board approved drinking water and surface water standards for PFAS in February, but it failed to pass limits on the chemicals in groundwater.

Following the board’s decision in February, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released new health advisory levels for four PFAS in June, two of which are at least a thousand times lower than the recommendations set in 2016. The DNR is proposing to set groundwater standards for those four substances. They include the chemicals PFOA, PFOS, GenX and PFBS.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The agency will consider recommendations from the EPA and the Wisconsin Department of Health Services’ proposed standard of 20 parts per trillion while crafting limits. The agency notes it may ask state health officials to revise recommended health standards based on new federal guidelines.

“This would really be setting a public health standard for groundwater, so we have a marker that people can look at and determine if the water is safe for human consumption or not,” Jim Zellmer, the DNR’s deputy administrator of the environmental management division, said.

While supporting development of regulations, the board’s chair Greg Kazmierski questioned whether the state is overselling the effectiveness of groundwater standards to address PFAS pollution.

“I don’t think we should be overselling that as soon as this passes, PFAS is going to go away because it’s not,” Kazmierski said. “At this point, it’s a much bigger problem. There’s legacy chemicals out there.”

Fred Prehn, the board’s former chair, said developing standards is another key to solving the problem. He said fixes include prevention of PFAS discharges and treatment of wells, which he said will likely prove extremely costly for communities. He added the science on PFAS is still evolving.

“Anybody who thinks this board just buried their head, and they didn’t want to deal with it was wrong,” Prehn said. “This is the first step to do it the right way.”

Regulators and health experts have raised concerns about the class of thousands of synthetic chemicals because they’ve been linked to serious health issues, including kidney and testicular cancers, thyroid disease and reduced response to vaccines. PFAS, or perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, don’t break down easily in the environment.

The proposal has garnered support from the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin, Wisconsin Conservation Voters and the River Alliance of Wisconsin. Residents of PFAS-contaminated communities have also been pushing regulators to restart the process to protect public health.

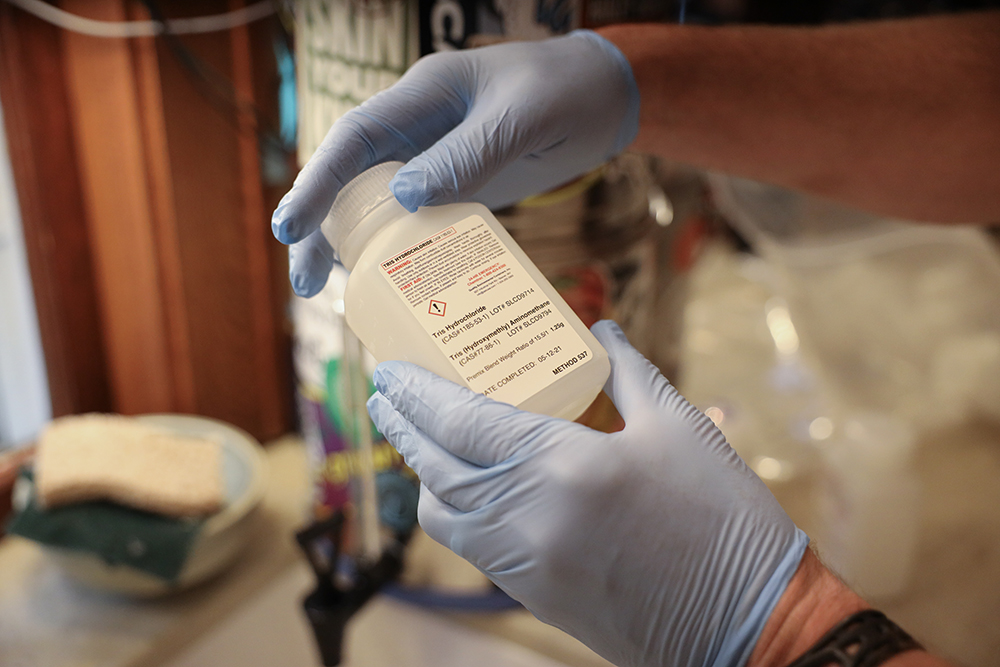

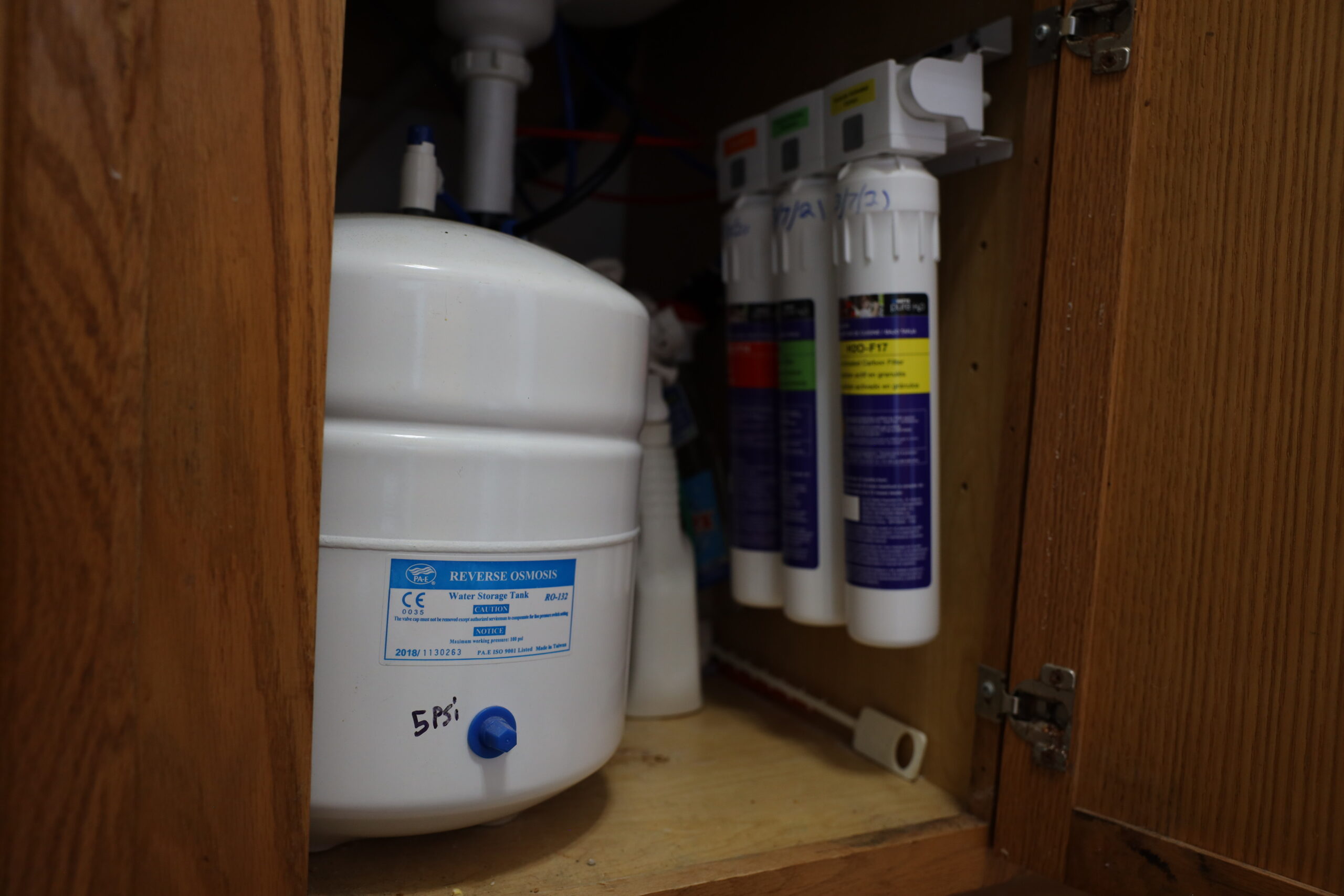

Town of Peshtigo resident Jeff Lamont said he’s been living on bottled water for drinking and cooking for five years after PFAS stemming from Tyco Fire Products’ fire training facility in Marinette polluted private wells.

“Frankly, at the age I’m getting, it’s getting very difficult to haul 5 gallon containers of water up and down from my basement for this purpose,” Lamont said. “PFAS exposure is a threat to human health and our state’s abundant natural resources even at very low levels.”

Lamont said concentrations in his well are about 140 parts per trillion. He noted that’s twice the state’s drinking water standard of 70 parts per trillion, seven times higher than DHS’ recommended standard and thousands of times higher than the EPA’s health advisories.

Town of Campbell Supervisor Lee Donahue said most wells tested in her community of 4,300 residents have detected PFAS, and many are using bottled water for cooking and brushing their teeth.

“At a recent holiday event, the second child to sit on Santa’s lap in our community asked for safe water,” Donahue said. “Think about that. Not a toy, not a bicycle. He asked for safe water.”

Even so, industry groups have repeatedly opposed the agency’s attempts to regulate the chemicals, calling on the DNR to halt work on groundwater standards.

Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce, the Wisconsin Paper Council and the Midwest Food Products Association argue there’s no clear consensus on limits for PFAS in groundwater. The coalition of groups noted state health officials’ recommendations are significantly higher than the EPA’s recently released advisory levels, and they said it doesn’t consider the state’s recently enacted PFAS standards in drinking water.

“There is no mention or acknowledgment that the state’s current drinking water standard will be considered when setting this groundwater standard,” the groups wrote in comments to the DNR.

The groups are once again urging state regulators to wait until the EPA adopts standards for PFAS in drinking water. The federal agency is expected to propose thresholds yet this year. The federal government does not oversee limits on chemicals in groundwater.

The coalition also targeted the DNR for not releasing an anticipated economic impact of the proposed standards until regulation is developed. The agency previously estimated groundwater standards for PFOA and PFOS would cost around $2.6 million each year, which critics called a vast underestimate. The DNR has maintained the state could see around $100 million in avoided health costs each year by regulating the chemicals.

Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce has mounted legal challenges over the DNR’s authority to regulate PFAS, including its ability to order cleanup under the state’s spills law. The lack of a standard thus far has complicated the DNR’s ability to force polluters to clean up PFAS contamination, according to John Robinson, a former DNR employee and co-chair of the emerging contaminants work group for Wisconsin’s Green Fire.

The DNR expects to hold one public hearing in 2024 after the EPA finalizes drinking water standards for the forever chemicals. The agency has more than two years to craft standards, and any regulation is subject to approval from the state Legislature and Gov. Tony Evers. PFAS have been detected in more than 50 communities across Wisconsin while the DNR is actively investigating almost double that many sites for contamination.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.