Registered nurse and Oshkosh native Mackenzie Summerville and her fiance spent more than a year looking for their first home.

In August, the couple finally had an accepted offer — after placing nine offers, many of which were above asking price, on different homes. They moved into their new home in Weyauwega, about a 35-minute commute from her job, last month.

“It was super frustrating,” Summerville said. “You get shut down so many times that you just legitimately think you’re never gonna find a house.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Many in Wisconsin have experienced similar frustrations in recent years.

From Madison to the Fox Valley, Wisconsin has a housing shortage. But it isn’t just a quality-of-life issue, it’s a workforce issue.

Wisconsin has a shortage of more than 120,000 rental units, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. And many municipalities are short on owner-occupied housing as well.

The city of Green Bay alone needs between 3,000 and 7,000 rental units, and between 4,000 and 9,000 owner-occupied units by 2040 to meet demand, according to a 2020 study.

Many communities in Wisconsin are in a similar situation. In fact, a 2019 study from the Wisconsin Realtors Association, titled “Falling Behind,” found the state had a severe workforce housing shortage.

Communities across the state are trying to attract workers in a tight labor market, but housing has made that challenging.

“That’s difficult to do when there’s no housing to actually let them live here,” said Jon Turke, vice president of government affairs for the Fox Cities Chamber of Commerce. “And the housing that is here is higher-end or just out of their price point.”

Wisconsin economists say the state didn’t build enough homes after the Great Recession, which — coupled with demographic challenges and a surge in demand — has caused the shortage and created a seller’s market.

While the Federal Reserve’s recent moves to raise interest rates will slow home buying, it is expected to increase rent costs. Experts say solving the housing shortage will require a multifaceted approach.

What’s causing the shortage?

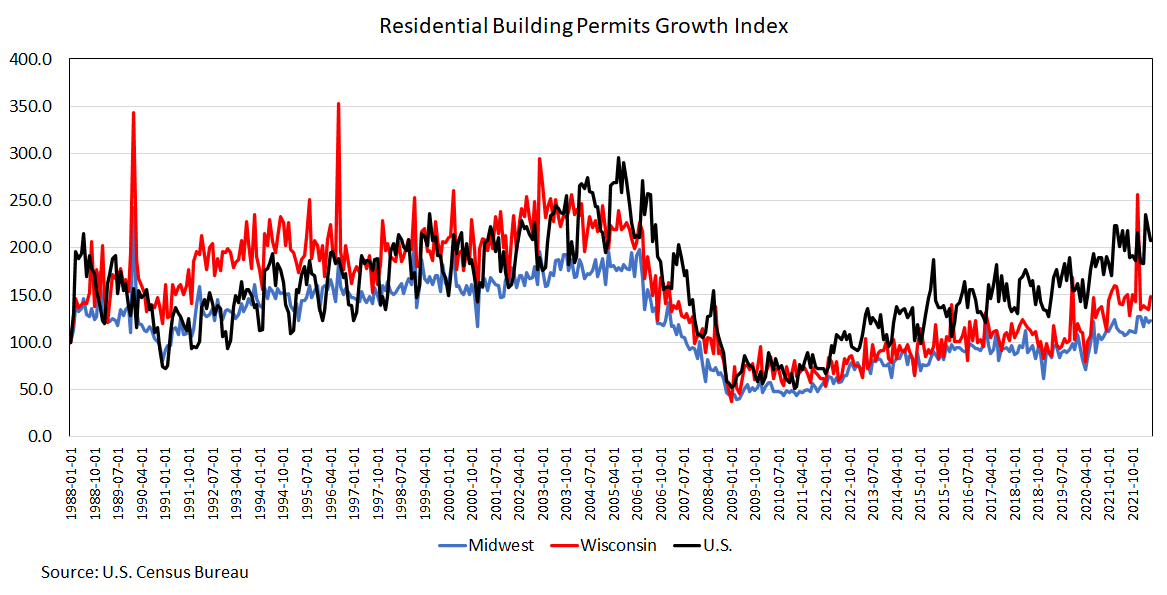

Wisconsin saw a record 30,000 single family home building permits authorized in 2004. By 2017, the number of permits authorized was less than 12,500, according to the Falling Behind report.

Prior to the Great Recession, University of Wisconsin-Madison applied economics professor and community development specialist Steven Deller said there was a typical “flow” of new houses being developed.

Construction of new housing “plummeted” after the housing bubble burst in 2008 and never came back, Deller said.

He said many of the developers in the starter home market were crushed during the Great Recession, banks have become hesitant to make loans for starter home developments and the cost of building materials continues to rise.

“The economics are just not in favor of building those starter homes,” he said. “And that’s where a lot of communities are really struggling because the developers that they do have that are interested are saying, ‘I just can’t make it pencil out.’”

On top of the lack of construction, demographics are playing a role in the housing shortage, according to Wisconsin Realtors Association economic analyst and Marquette University economics professor David Clark.

He said baby boomers are living independently longer than previous generations at a time when millennials are trying to purchase their first homes.

“As a consequence, we still have more potential buyers out there than there are sellers,” Clark said.

That means the housing market is a “seller’s market,” where home sellers have more leverage than buyers in negotiating price, he said.

How is housing a workforce issue?

Before the pandemic, many municipalities were struggling to find workers, according to Deller, who works with communities across the state through UW-Extension.

One of the common issues among communities struggling to find workers was housing. Deller said homes were either too expensive for prospective workers or they were too old and inadequate.

“There’s a lot of communities across Wisconsin that have been struggling to try to address that issue,” he said.

Wisconsin Economic Development Corp. CEO Missy Hughes said housing is critical to allowing people to fully participate in the economy — along with reliable transportation and child care.

“When you apply for a job, you have to write down your address,” Hughes said. “So if you are unhoused, or you’re in temporary housing, then that creates a challenge for even getting a job.”

Clark said housing can be a more acute workforce issue in communities with a higher cost of living and a lack of supply.

“If you have a shortage of housing, that drives up the cost of housing and makes it difficult for new workers to afford it,” he said. “Or it may make it so that if they (workers) want to take a job, they have to live a greater distance away from their place of work.”

The workforce housing situation could be further complicated by the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes.

Clark said raising interest rates will slow demand for home buying, but not for rent.

“If you have a shortage in the existing home market, that will move people who form households into rental housing,” he said. “That’s going to increase demand for rental housing, which will then put upward pressure on those prices.”

What can be done?

Experts say solving the housing shortage requires new construction, zoning reform, upgrading existing housing and demographic shifts.

Earlier this year, the League of Wisconsin Municipalities partnered with several statewide groups to release a toolkit for municipalities that includes zoning reforms to help promote affordable housing.

The toolkit includes recommendations to allow for narrow lots, accessory dwelling units, multi-family developments in commercial districts and duplexes in more residential zoning districts.

“If you have areas that, you know, a builder might say, ‘Hey, this would be a great place to develop,’ but it can’t be rezoned for that purpose, you’re going to continue to exacerbate the problem,” Clark said.

Additionally, Deller said addressing building codes could improve the starter home market by forcing existing housing stock to be upgraded.

“The problem is a lot of communities don’t have the political will to do anything to enforce that,” he said.

The housing market also may loosen as more baby boomers move out of owner occupied housing, Clark said.

“Father time is progressing, so the supply side will ultimately increase over time,” he said. “And more homes will find their way onto the market and fewer buyers will be competing for those homes. Ultimately, we will move back to something closer to a balanced market.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.