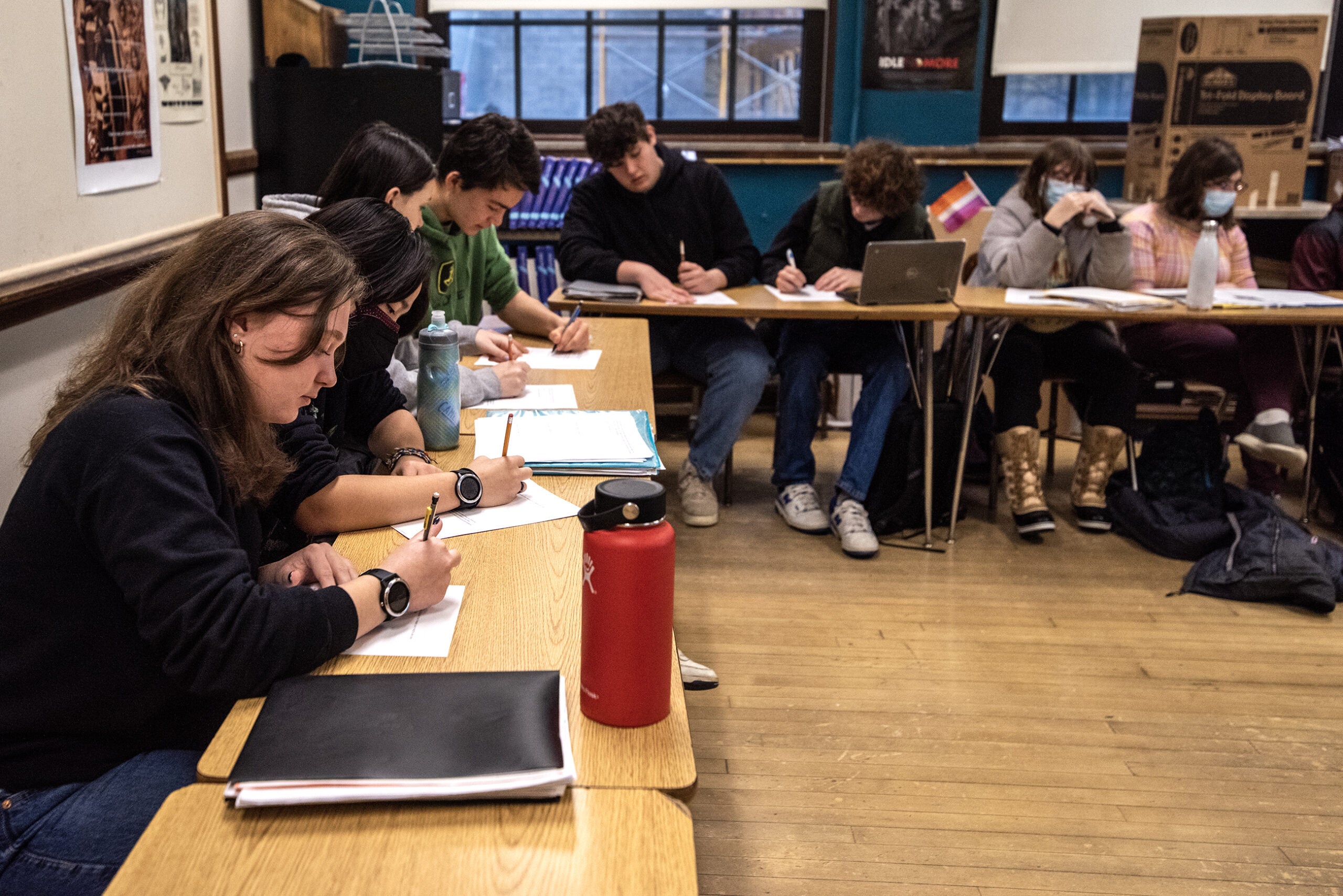

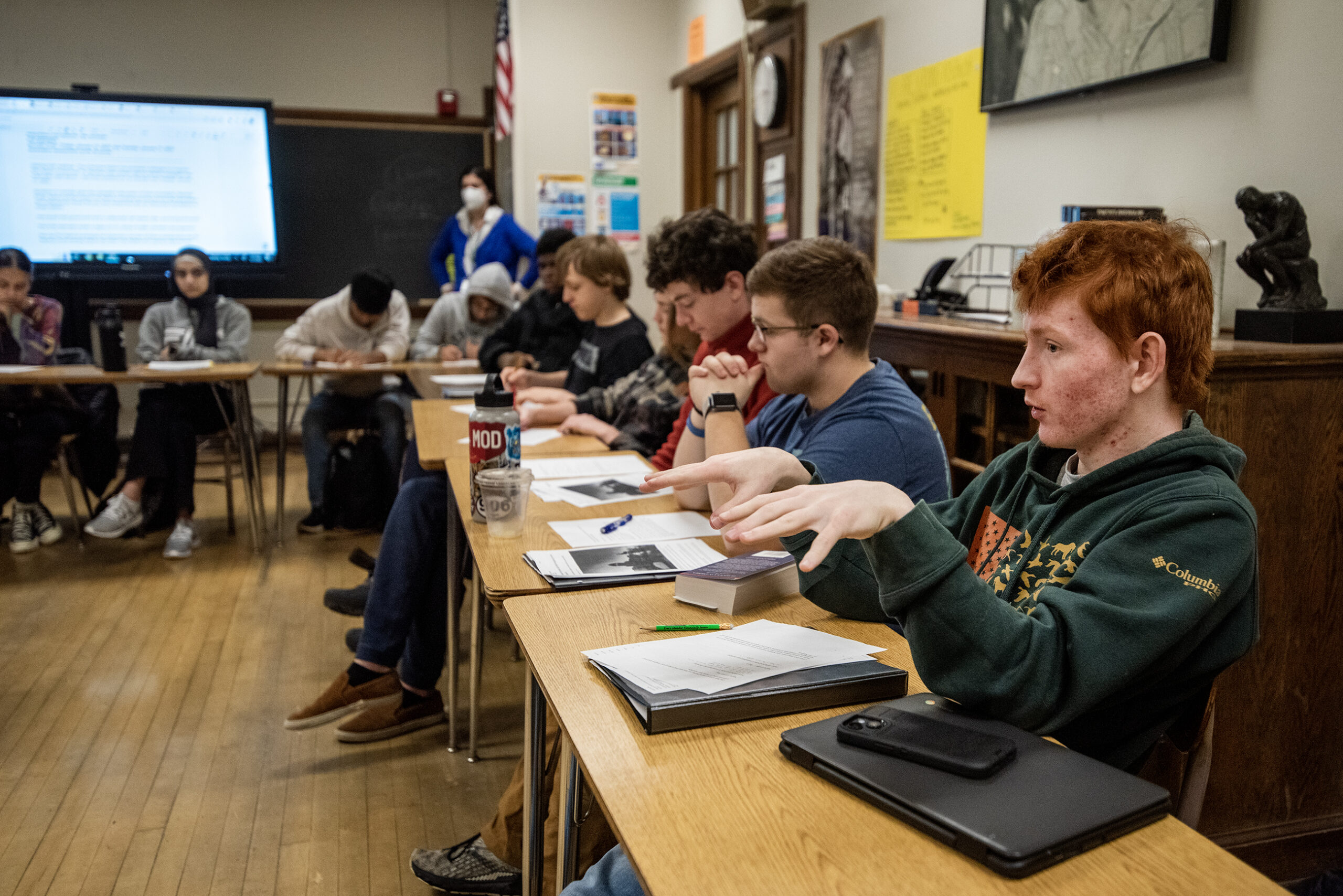

On a Tuesday morning in January, Carrie Bohman, a social studies teacher at Madison West High School, posed questions to her students in their Wisconsin First Nations class.

“How was the reservation system a legacy of the U.S. policies of settler colonialism and expansion?” she asked, and, “How can tribal sovereignty be maintained?”

Bohman asked her students to prepare for a socratic seminar by bringing questions and reading news articles about Native American reservations and representation in Congress.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

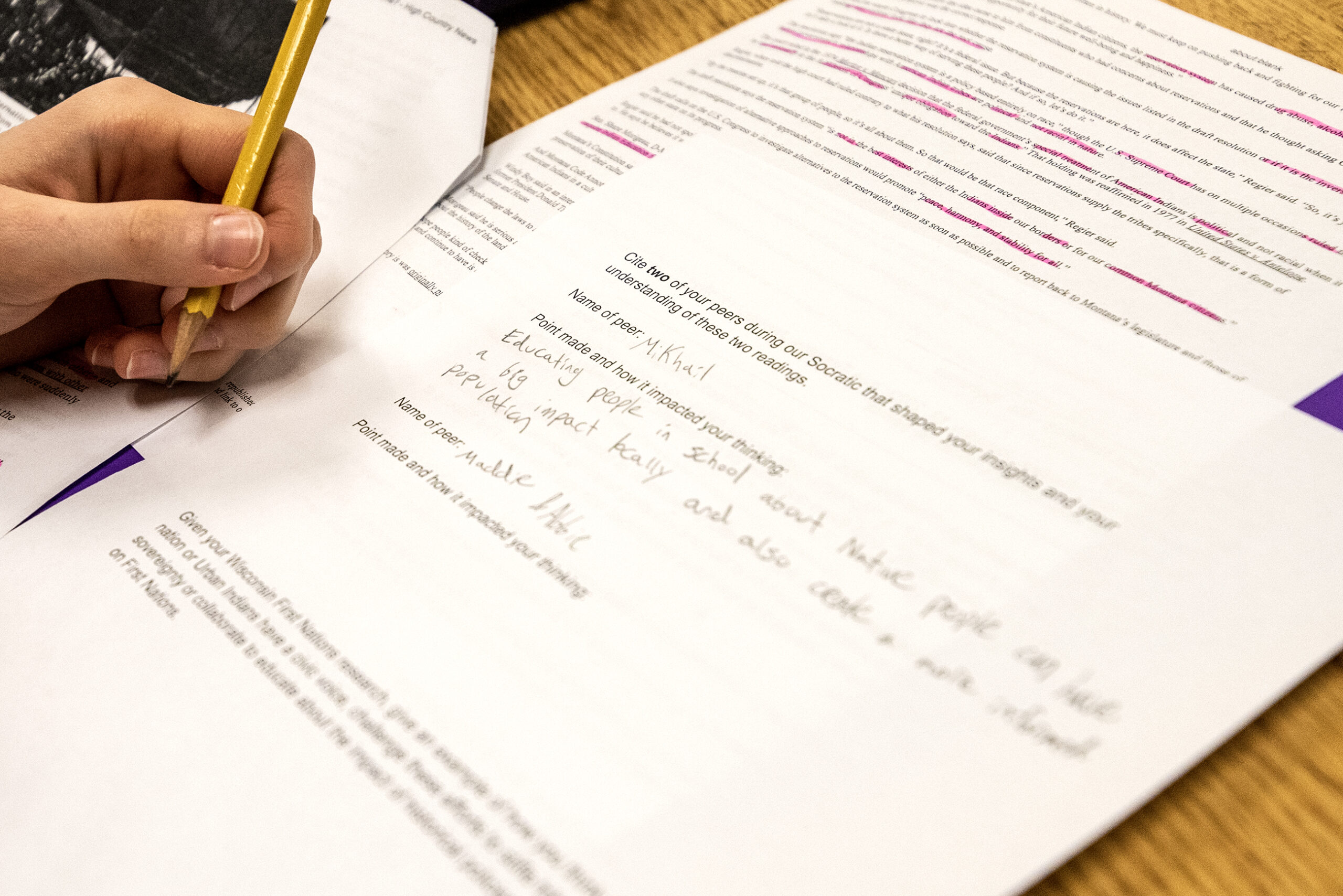

First came Abby O’Callaghan: “Given the legacy of the federal government and its involvement in the dispossession of Native peoples, how can we move forward? What can be done at the local and state levels to ensure that there’s a real change in policy?”

Later came Mikhail Shevelenko: “How can we learn from misconceptions of Native laws by the U.S. government and how can we prevent misconceptions in the future?”

Classes like Bohman’s, where students dive into the history of Wisconsin’s First Nations, are of interest to Maria Novotny. She started thinking about her education when she left Wisconsin to get her master’s degree and doctorate in Michigan, where she received mentorship from Indigenous scholars.

Conversations with her Indigenous colleagues got her curious about how Wisconsin teaches Indigenous history. She wrote into Wisconsin Public Radio’s WHYsconsin asking how educators are teaching curriculum about tribes and Indigenous people in the state.

Bohman’s classroom is just one example of how some Wisconsin teachers are connecting Indigenous histories and cultures with current issues and events — and much of the work traces back to a state law passed in 1989 called Act 31.

The law, also called American Indian Studies in Wisconsin, mandates public school districts and public and private universities and colleges provide instruction on the histories, cultures and sovereignty of tribal nations in Wisconsin. It went into effect in 1991.

The legislation came as a response to racist violence in northern Wisconsin in the 1980s and early 1990s. Members of the Ojibwe tribe were spearfishing on ceded territory. They were met by armed anglers and protestors at public boat landings, blocking them from exercising a right the Wisconsin Ojibwe people reserved.

Some anti-treaty protesters argued spearfishing would hurt the tourism economy, while others falsely claimed they would deplete the fisheries. Many shouted racist slurs.

Ojibwe retain the rights to fish, hunt and gather through federal treaties signed in 1837, 1842, and 1854. But those were ignored by the state and led to legal battles that lasted decades. The treaties were ultimately recognized by the federal courts in the 1983 Voigt decision.

Spearfishing protestors stand by a fake gravestone they placed at Lake Nokomis in northern Wisconsin, where members of the Ojibwe tribe were spearfishing in May 1989. Allen Fredrickson/AP Photo

Members of the Ojibwe tribe spearfish in Butternut Lake in northern Wisconsin in May 1989. Protestors on the shorelines attempt to block them from exercising a treaty right. Allen Fredrickson/AP Photo

The violence and racism against the Ojibwe people was deeper than a misunderstanding over fishing and treaty rights, and was considered the last straw, said J P Leary, who is of Cherokee descent and served as the American Indian Studies consultant at the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction from 1996 to 2011.

”Generations of Wisconsin people were not provided meaningful opportunities to learn about the history, culture and tribal sovereignty of their Native neighbors. And that, at one particular time, had explosive, violent consequences,” said Leary, who is now an associate professor of First Nations studies, history and humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay and the author of the book, “The Story of Act 31: How Native History Came to Wisconsin Classrooms.”

State leaders saw the gap in education and knowledge surrounding Native history and rights and knew they had to do something.

Act 31 aims to correct previous curriculum policy decisions that misrepresented or failed to represent Native people, Leary said.

“The real policy problem that Act 31 is addressing is the lack of meaningful opportunities to learn accurate, authentic information about the federally recognized tribes and bands in Wisconsin,” he said.

Teaching requires learning and, in some cases, unlearning

David O’Connor, whose Ojibwe name is Bwaakoningwiid, is now the DPI’s American Indian Studies consultant, a job born out of Act 31 and one he has held since 2012.

O’Connor works with educators on integrating the histories, cultures and tribal sovereignty of the Indigenous nations of Wisconsin into curriculum to help schools meet this mandate. He leads full-day trainings with school districts, hosts webinars, works with different CESA regions and presents at local, regional, state and national conferences.

He also works with individual teachers to create action plans with short- and long-term goals through the Wisconsin American Indian Studies Summer Institute.

O’Connor practices what he calls “the four Is”: Inform, include, integrate and infuse. Through training opportunities, educators go from introducing resources about Native American history in Wisconsin to speaking more fluidly about individual nations and sharing information without fear of making mistakes.

He offers educators resources on topics such as treaty rights, Indigenous languages, festivities, food and tribal sovereignty, among others.

“They just run with it and learn from it. I always call that growth mindset versus a fixed mindset: Understanding that your practice can continually grow over time, rather than just sticking with the status quo,” O’Connor said.

Still, incorporating the content can sometimes be overwhelming for educators. Nationally, there are 574 federally recognized tribal nations. Wisconsin is home to 11 federally recognized tribes.

O’Connor said it’s best when educators can focus lessons on individual nations because they have different histories, cultures, tribal governments, constitutions, traditions, values and customs. And he emphasized that teaching Native history throughout the academic year is better than limiting it to one holiday or one month.

He also advises educators to weave in contemporary voices of Indigenous peoples and nations. When he asks educators to name three famous Native Americans today, they often falter and name historical figures rather than First Nations people today.

“Representation matters,” O’Connor said.

Students learn directly from tribal members and communities

Since the law was passed more than 30 years ago, Wisconsin educators have been working to integrate this history more deeply into their lessons.

Jeff Ryan is a social studies teacher at Prescott High School, southwest of River Falls along the Minnesota-Wisconsin border. He said he looks to Native people for their trust in him and willingness to share their knowledge.

Since 2000, Ryan, who is white, has taken nearly 400 students on four-day trips to the Lac du Flambeau reservation in north-central Wisconsin to learn about the history, culture, government and community. They talk with tribal elders, do craft work and tour cultural sites.

“To gain a full understanding of the experience, whether it be the history or the contemporary issues connected Native people, you have to access and talk with Native people,” he said.

In class, Ryan dismantles stereotypes and explains certain words are no longer used because they’re slurs.

“We talk about how words change, meanings of words change, times change,” he said.

He also tells students on their first day of class that there are more than 500 tribal nations in the United States. Then, Ryan asks students what that means.

“It means that there’s 500 ways of thinking, 500 ways of talking, 500 ways of living, 500 ways of being — that’s about as diverse as it gets,” he said, adding, “it’s an impossible thing to talk about First Nations history in a trimester.”

Digging deeper to teach Wisconsin’s Native history

Act 31 requires the subject matter to be taught at least three times in grades K-12, but because Wisconsin is a local-control state, it’s up to school boards and administrators to adopt standards and create and implement curriculum.

In the early 1990s, statewide conferences helped teachers learn about the history of Indigenous peoples and nations of Wisconsin, and DPI’s American Indian Studies Program hosted sessions across the state, including at the Wisconsin Council for Social Studies.

The agency also republished materials and shared them with every district in the state. The goal was to help get resources to as many educators as possible.

Over time, educators expressed a need to have resources in one place to help support teaching and learning, said Alyssa Tsagong, PBS Wisconsin’s chief curiosity officer.

To fulfill this need, PBS Wisconsin Education worked with tribal leaders, UW-Madison’s School of Education and the DPI to create WisconsinFirstNations.org. Launched in 2017, the website offers a wide range of resources, including books, videos, maps and lesson plans — and materials continue to be added.

Some educators find it difficult when they encounter the content for the first time, O’Connor said, and it can present challenges as they unpack, unlearn and relearn information.

He said he wants colleagues across the state to “get into spaces where they can dig deeper and have an opportunity to really challenge themselves to become more knowledgeable about the subject.”

Some critics say Act 31 has no teeth, but Leary said forcing compliance is not a solution.

“If we define the problem as, ‘they’re not providing instruction,’ then the solution to that problem is to help them build capacity so that they can provide instruction,” Leary said.

Leary said some districts are not meeting the Act 31 mandate, something he blames on a lack of understanding, capacity and political will.

And even today, he said, some teachers still face pushback for teaching the content.

“We just need those school board members and those school administrators to stand up and tell their teachers, ‘This is the right thing to do. It’s the required thing to do. We’re going to provide you with the resources to do it, to do it well. And we’re going to protect you when the backlash comes,’” he said.

A 2014 survey found that of the school administrators that responded, “a large majority” of their schools and districts include instruction required by Act 31 but also signaled a need for more instructional materials and professional development.

‘Respect their history’

Back in Bohman’s classroom at Madison West High School, students continued discussing issues related to tribal sovereignty — after the bell rang.

Mikhail, 16, said he’s a first-generation immigrant from Russia. He identifies as caucasian, but the specifics of his race are not fully known because he’s adopted. He said he’s always believed in protecting Indigenous rights, but understanding their history and relationship with the U.S. government puts it all in perspective.

“Now I know why we need to respect their history … why we have to uphold these promises that we’ve given in the past to these nations — because they have helped us so much in the founding of our nation and upkeep of it,” he said.

Abby, 17, said she identifies as white but is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation, which shapes her worldview. She said she had a fairly strong understanding of Indigenous history, but the class gave her a deeper understanding of Wisconsin’s Indigenous nations and their role in current affairs.

To her, the conversations help move the needle forward.

“I think they’re really critical to understand the history of our nation and more specifically, Wisconsin, and then how we can move forward to repair those relationships, and reaffirm the sovereignty of those nations,” she said.

This story was inspired by a question shared with WHYsconsin. Submit your question below or at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it.