More than half of Wisconsin schools restrained or isolated students to control their behavior during the last school year, according to data released by the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI) this week.

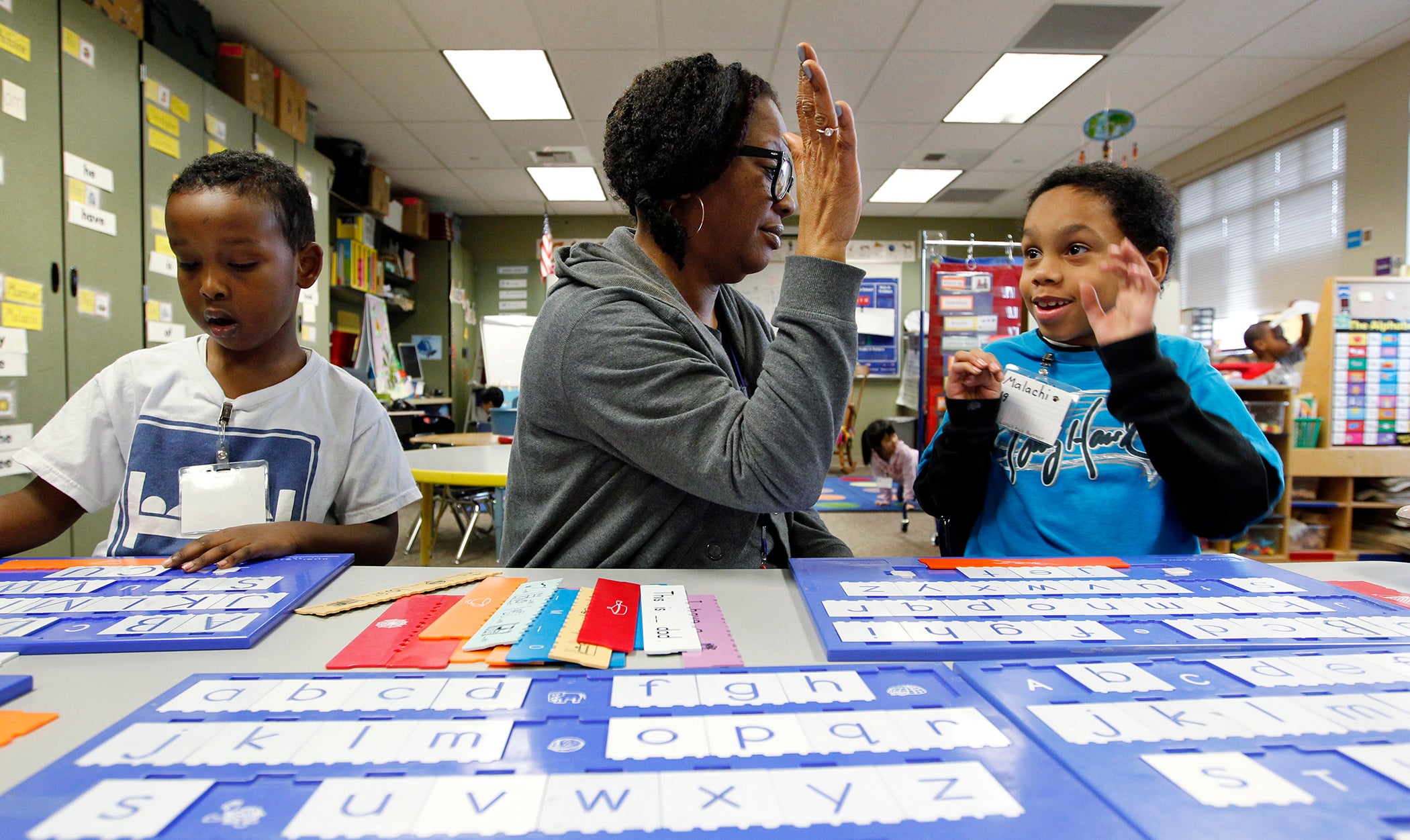

The data, which was collected because of changes to the state law on restraint and seclusion, also shows that elementary school students and students with disabilities were more likely to be restrained or secluded. The 30 schools that reported the most seclusion incidents were all elementary schools.

Joanne Juhnke, advocacy specialist in special education with Disability Rights Wisconsin, said the practices are more common for lower grades because of the students’ size and the “relative ease of physically overwhelming” smaller children. However, it comes with a particular cost to elementary school-aged kids.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“These are happening with young children, children with whom this is an impressionable time, and can cause emotional harm, to be physically overpowered or shut in a blank little room that they’re prevented from getting out of,” she said.

State law defines restraint as a restriction that immobilizes or reduces the ability of students to freely move their torso, arms, legs or head; and seclusion as the involuntary confinement of students apart from other students in a room or area that they are physically prevented from leaving. It’s meant to be used as a last resort, and to manage a crisis rather than as a disciplinary measure, said Barb Van Haren, assistant state superintendent for the Division for Learning Supports at DPI.

“The (state law) actually prohibits the use in general, and making sure that the only time it is used is when the behavior is a clear, present and imminent risk to the physical safety of students — the students (being restrained or secluded) themselves, other students, or other staff.”

Some of the schools with the highest numbers of seclusion incidents also reported using the tactics on a large share of their students with disabilities in the 2019-2020 school year.

At Butte des Morts Elementary in Menasha, 20 of the 217 students who were secluded and 20 of the 256 who were restrained were students with disabilities — nearly a quarter of the school’s 81 total students with disabilities.

Sheboygan’s Jackson Elementary, similarly, reported using seclusion on 19 out of 79 students with disabilities, and restraint on 13. In total, it restrained 72 students and secluded 144.

In Milwaukee, home to the state’s largest school district, 52 students were secluded and 331 were restrained, including those at Milwaukee Public Schools, public charter schools, and voucher students at private schools who also had to report to DPI. Students with disabilities made up 71 percent of those secluded and 57 percent of those restrained.

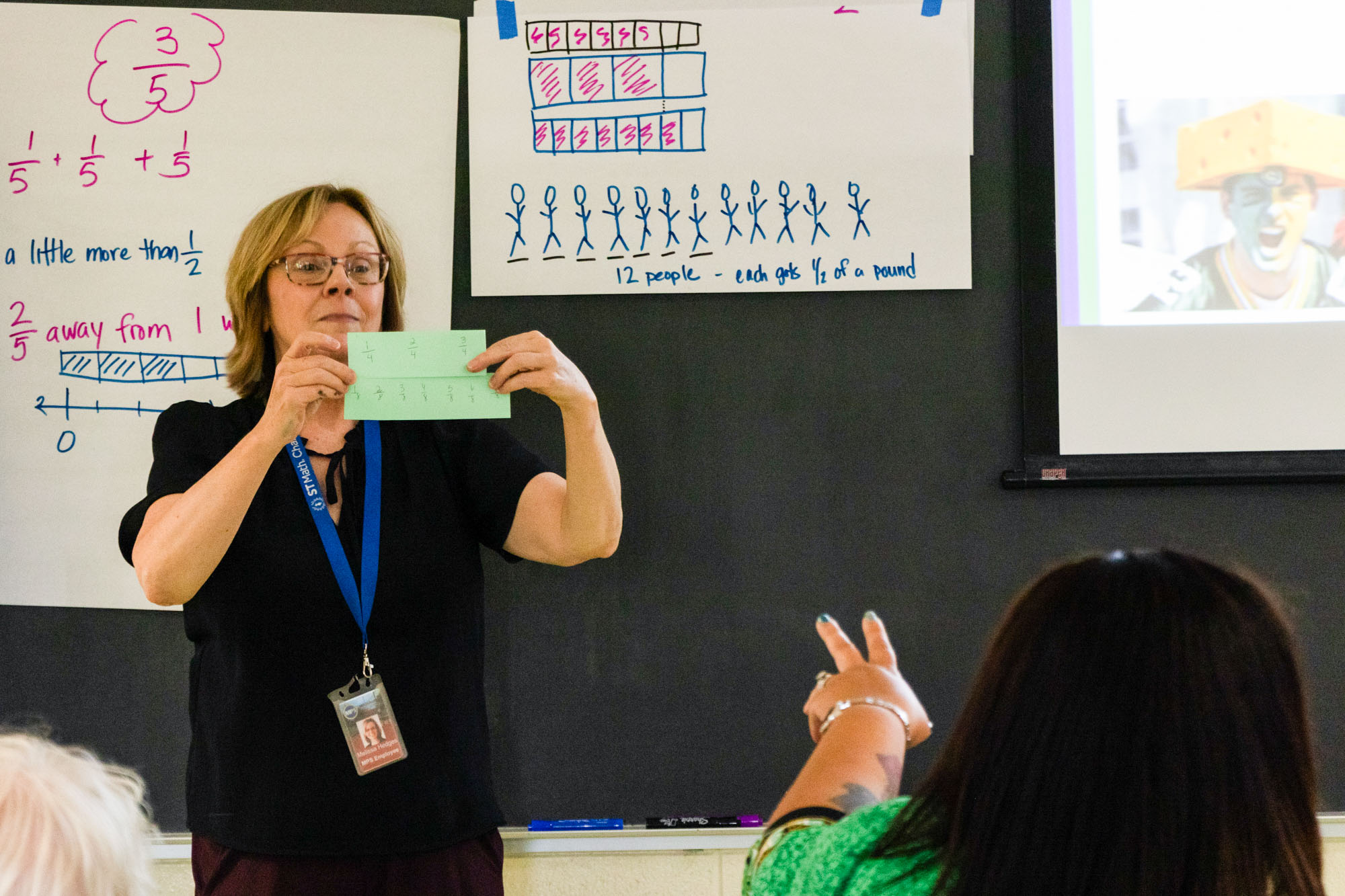

Van Haren works with schools to develop alternatives to restraint or seclusion. She said schools that have adopted a “trauma informed” model tend to do better at reducing the use of those last-resort measures.

“I really think a mental health framework and an approach of trauma-informed care is essential,” she said. “We need to be able to recognize (trauma) and address it.”

This is the first year schools have had to report the number of seclusion and restraint incidents to the state agency. Previously, schools have sent that data to their school boards, but Juhnke is hopeful the statewide view will push schools that have higher rates toward resources and alternatives.

“Even just the data is a huge step forward so families can see what is going on in their districts; so districts can see what is going on in other schools, what is going on in other districts; and so organizations can see where are the trouble spots, and where is more assistance needed,” Juhnke said.

There are no federal laws outlining seclusion and restraint policies in schools, though the last decade has also seen repeated attempts to pass laws at the national level. In Wisconsin, a coalition has been pushing for changes to the state’s policies on restraint and seclusion for years. Juhnke’s organization, as well as the child advocacy groups Wisconsin FACETS and Wisconsin Family Ties, asked for changes that would get incident reports into families’ hands, prompt debriefing meetings and reassessments of students’ individualized education plans after restraint or seclusion was used, and require schools to submit their data to DPI, all of which made it into the changes signed into law in March 2020.

The group still sees work to do, though — Juhnke said she wants to see the data broken out by how often law enforcement officers are doing the restraining. She also wants private and charter schools that take public school students through the Milwaukee, Racine and statewide voucher programs to have to submit seclusion and restraint data for all their voucher students, not just the ones on the special needs scholarship program. Ultimately, Juhnke said, she’d like to see schools do away with seclusion altogether.

“How do you get a child who is so out of control that they are a physical danger into a seclusion room?” she said. “You have to physically overpower that child to get them into the seclusion room — why is the seclusion room necessary, if you’re already going to be using restraints?”

Even under last year’s changes, the data reported to DPI is limited — it’s only broken out by disability status; not by race, gender, age or any other demographic distinction.

“Disproportionately, we know our students of color are often overrepresented in discipline numbers as well, and although we haven’t collected that data in terms of seclusion and restraint, we know that from suspensions and expulsions,” said Van Haren.

The data reported this year is also an incomplete picture. Because schools shut down in March, the 2019-2020 data only reflects part of the year. The current school year isn’t likely to add much clarity, as many school districts haven’t been holding classes inside school buildings, which will make it impossible for them to compare that kind of disciplinary data to schools that are in person.

Looking forward, though, Van Haren said she does have some concerns that children coming out of the pandemic will be carrying more trauma, which could escalate into staff restraining or secluding students if they don’t understand why students are acting out or how to help de-escalate those situations.

“Having school social workers, school counselors, school psychologists, et cetera; having good training of staff around trauma-sensitive schools and around mental health, I think is imperative,” she said.

As in so many cases, Juhnke notes, it comes down to an ounce of prevention being worth a pound of cure — keeping class sizes small enough that teachers aren’t overwhelmed, funding individualized help for students who need it, using planning meetings for students with individualized education plans and other specialized learning plans to identify what might set students off and game out how to handle the situation if they act out.

“There are all of these planning opportunities for how to think about, what are the barriers? How do we teach these students to self-regulate? What triggers do we need to avoid?” she said. “When you have the commitment on the part of the school, and you have the resources, those are the best approaches.”

Correction: This story was updated to clarify Milwaukee schools data.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.