Reading instruction for Wisconsin’s youngest students will be revamped under a new law signed into law by Gov. Tony Evers on Wednesday.

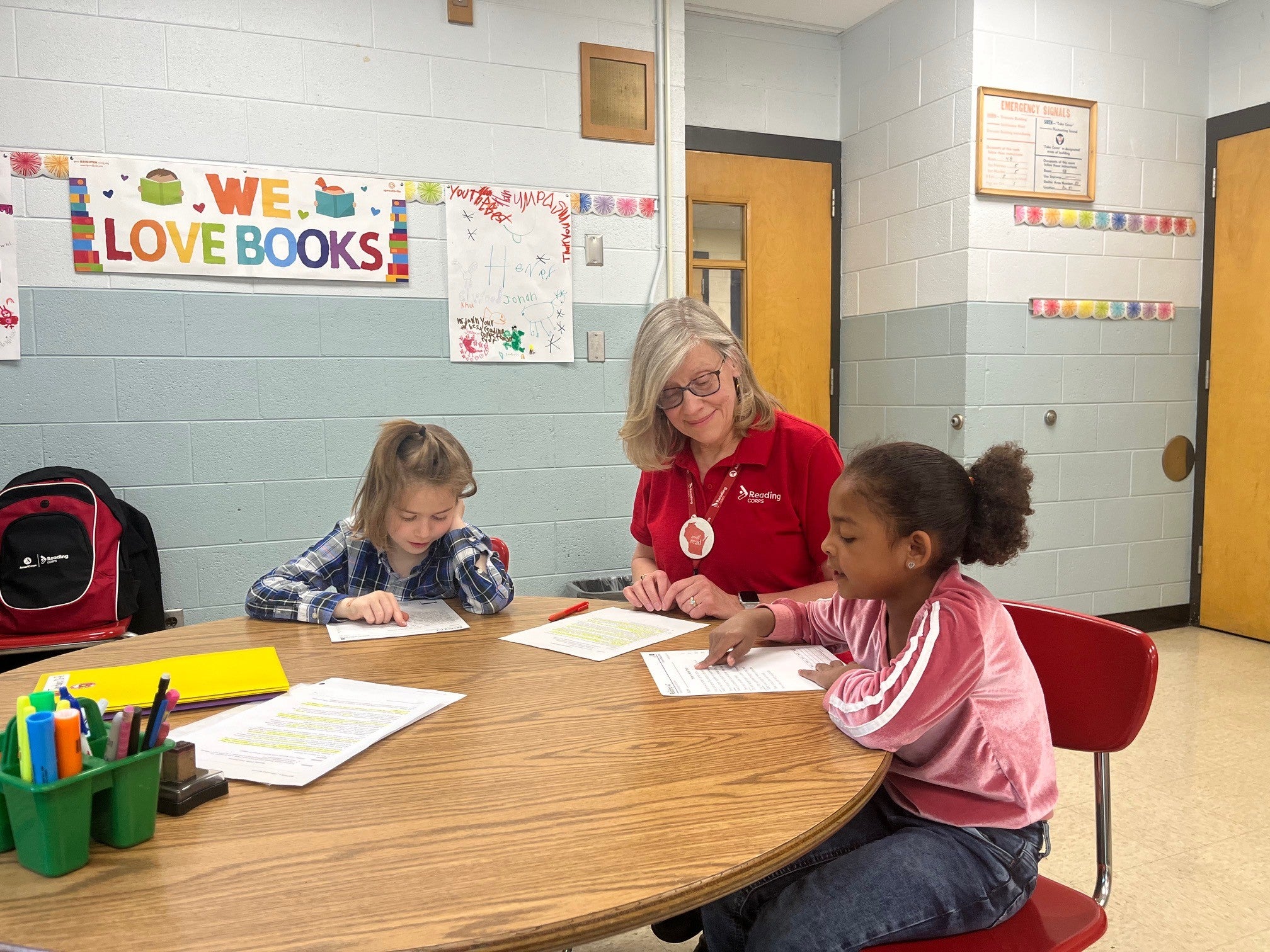

The state will spend $50 million dollars to create a new literacy office, hire reading coaches and shift away from what has been known as “balanced literacy” to a “science of reading” approach.

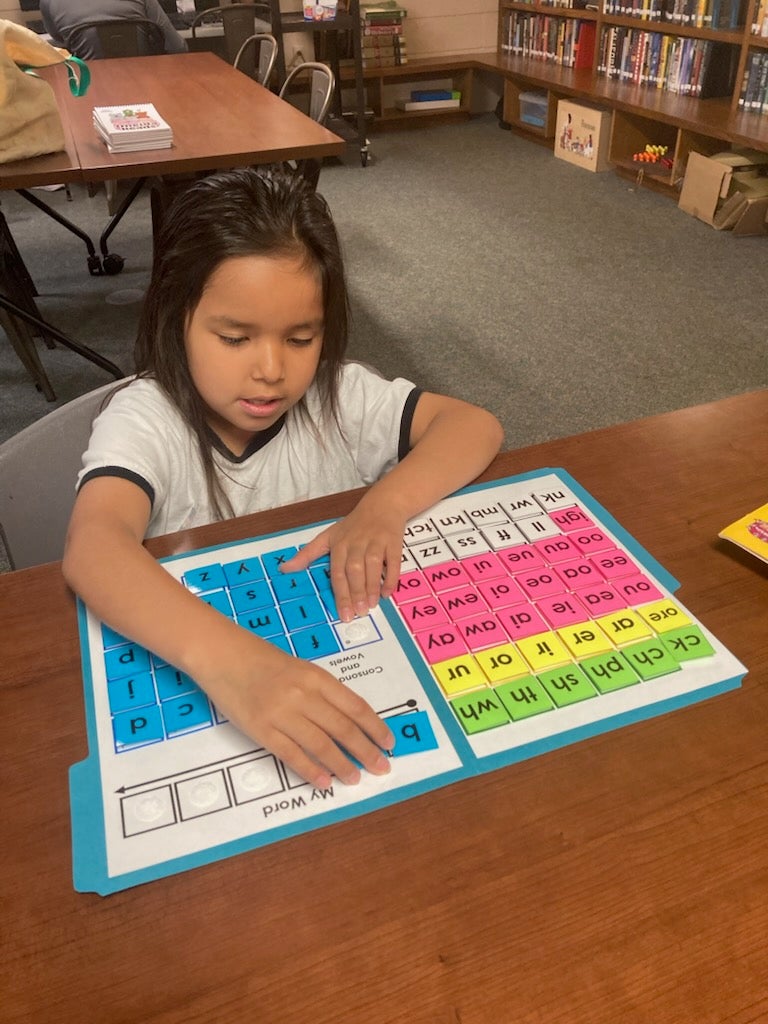

Students will now be taught to read with an emphasis on phonics with the hope to address the state’s lagging reading scores.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“We have to ensure our kids have the reading and literacy tools and skills to be successful both in and out of the classroom,” Evers said in a statement.

Republicans who introduced the bill hailed it as critical to address what they call a literacy crisis in Wisconsin.

Only 33.8 percent of third graders were proficient in reading on the most recent Wisconsin Forward Exam. Wisconsin’s achievement gap between Black and white fourth grade students in reading has often been the worst in the nation.

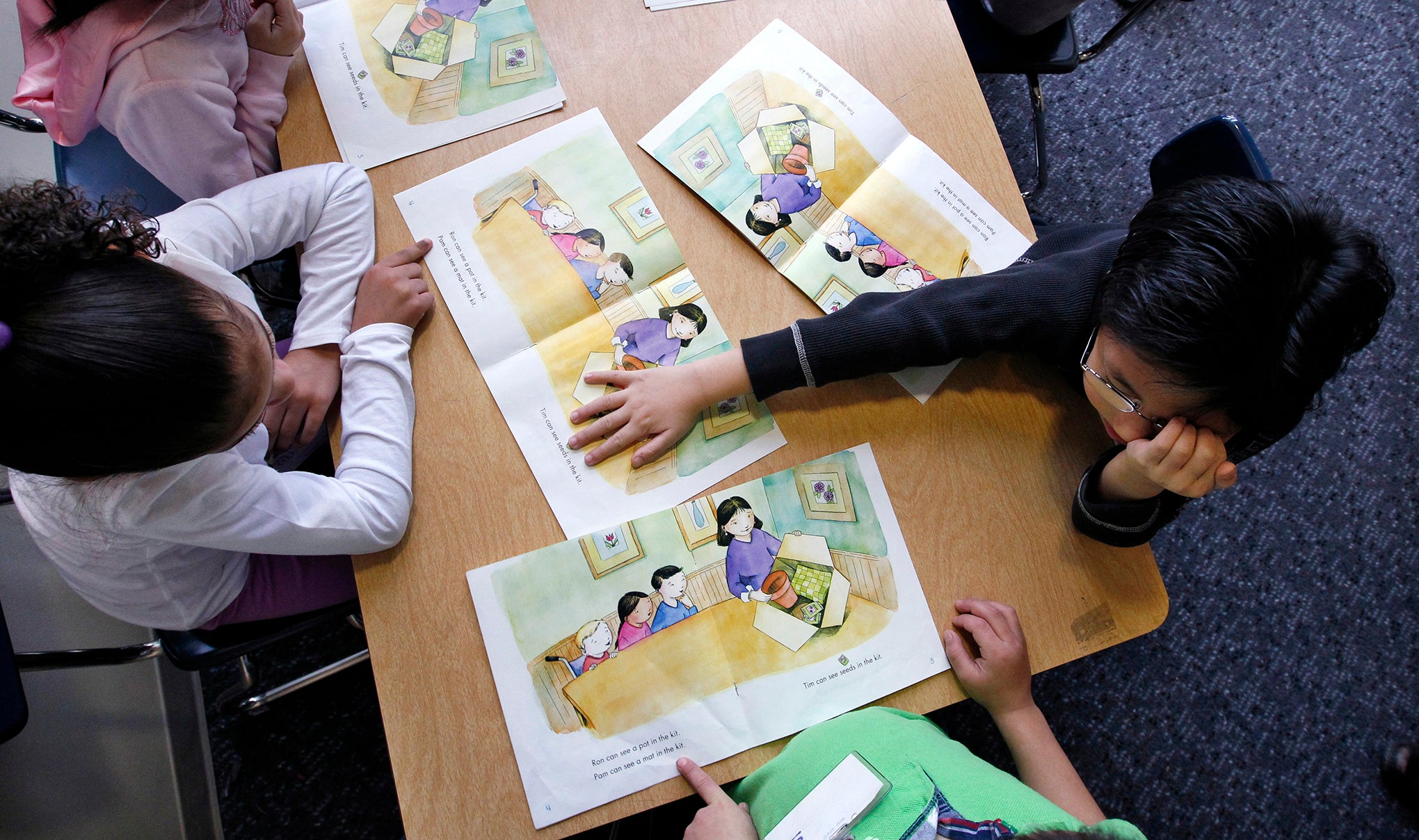

Instead of learning how to read through pictures, word cues and memorization, children will be taught using a phonics-based method that focuses on sounding out letters and phrases.

According to the state Department of Instruction, only about 20 percent of school districts are using a phonics-based approach to literacy education. Other reading curriculums that don’t include phonics have been shown to be less effective for students.

“Wisconsin will now align with 31 other states that already utilize the Science of Reading approach,” Sen. Duey Stroebel, R-Cedarburg, who co-sponsored the bill, said in a statement. “The Right to Read Act will get Wisconsin back on track to close achievement gaps in reading and language arts.”

Evers called the bill a step in the right direction, but said more is needed to address student needs including mental health challenges and school lunches.

“The bottom line for me is that reading curriculum is only one small part of the equation to ensuring our kids are prepared for success — we know that kids who are hungry, in crisis, or experiencing other challenges at home might have trouble focusing in class or on their studies, be distracted or disengaged at school, and have a hard time completing their coursework,” Evers said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.