Amy DeBroux described the 13 years of advocating for her daughter’s mental health as being at sea: periods of crisis followed by calm.

From 2005 to 2018, DeBroux spent hours discussing her daughter’s educational and mental health support needs. The scenes were familiar enough for DeBroux, thanks to her background in education. Normally, she would’ve sat on the same side of the table as the specialists, advocating for her students.

But the tables had quite literally turned.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Before she adopted her two children, DeBroux worked in Kaukauna and Appleton school districts, as well as a Connecticut school, for 10 years. Now, both her children needed behavioral health support, with one of her children specifically needing a tailored program following her autism diagnosis.

The team of educators — teachers, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, school psychologists — came with a list of suggestions for her child’s individualized education program, commonly referred to as an IEP. She absorbed the information as it was given, but still, she felt overwhelmed at times.

“Any parent who has a child with special needs goes through a grieving process. That vision you had for your child, what you thought your child would be, is now different,” DeBroux said. “When you actually go through that process, you’re asking so many questions: What are we going to have to do to help navigate things for our child? And how do I support myself supporting that person?”

Those questions are woven into a grim dynamic for thousands of Wisconsin families. At a time when studies indicate a desperate need for more mental health care services among Wisconsin’s children and adolescents, the number of providers is simply not where it needs to be.

As a result, the burden falls on parents and other family members, or on teachers and other school staff, none of whom likely have the necessary time or tools.

“If you have a cold, you go to the doctor right away. If you have a mental health issue, you have to fill out a form that says you’re not eating, that says you’re not sleeping. You have to wait six weeks or longer to get an appointment. And then you may get an appointment with someone who really doesn’t resonate with you,” said Linda Hall, director of Wisconsin Office of Children’s Mental Health.

The irony is that, due to a number of initiatives funded by federal pandemic relief funds, Wisconsin schools recently have increased the number of social workers, counselors and psychologists, according to the Wisconsin Office of Children’s Mental Health. The bad news? In all three categories, Wisconsin has remained far below the recommended ratios of students to mental health professionals.

The American School Counselor Association, for example, recommends one school mental health counselor for every 250 students — a ratio that is generally accepted across the country.

The latest school-counselor-to-student ratio in Wisconsin, according to data from 2021-2022, was 378 to one.

The result, for families like the DeBrouxes, is that half of Wisconsin parents had difficulty obtaining mental health services. And, perhaps no surprise, almost the same percentage of children ages 3 to 17 with mental health conditions did not receive treatment.

Further, the gains that were made with pandemic relief funds are temporary, said Matt Kaemmerer, director of pupil services for Oshkosh School District. Grant funds cannot support the long-term hiring of mental health professionals.

“It’s really hard to hire permanent school staff members with that grant funding, because who’s going to want to come and work in the district when they don’t know if they’re going to have a position the following year?” said Kaemmerer.

Mental health conditions in children are among the most pervasive. They’re also the costliest to treat.

DeBroux threw herself into the ring to learn as much as she could about the needs of her young children. As an educator, not only had she encountered students in various developmental stages — a knowledge that helped her forge ahead — but she also understood the jargon associated with an IEP.

Perhaps most important of all, however, was the relatability of her circumstances: She met other harried parents in the middle of similar challenges with their children.

Getting an intake and finding the right fit for a counselor proved difficult for DeBroux and her children, especially with such a slim selection of providers from which to choose in the first place. The wait times to see a pediatric psychiatrist, too, can stretch from six months to a year.

“The challenge is getting into those appointments,” DeBroux said. “That’s the most frustrating part. If you tell a doctor your child has a heart murmur, there’s not going to be a year-long wait time to get help.”

That tracks with recent data from the U.S. Department of Education in which 70 percent of public schools reported a dramatic jump in students seeking mental health services following the pandemic, despite nearly half of schools also saying they couldn’t effectively provide counseling support for these students. Additionally, 76 percent of public schools reported an increase in staff voicing concerns about their students’ showing symptoms of depression, anxiety and trauma.

For so many families, the pandemic exacerbated an already fragile situation, said Jessica Frain, school mental health consultant for the state Department of Public Instruction. Many children fell behind in school or experienced some form of stress at home. The pandemic shattered the comfort of daily routines.

But well before the pandemic, parents faced crushing medical bills following counseling sessions for their children.

Mental health disorders are the most expensive conditions to treat among children aged 5 to 17, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which found in one study that having a mental health disorder added $2,874 a year to total health care costs. And a recent poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that, of the 100 million Americans that have some kind of health care debt, 20 percent is owing to mental health services.

“There’s a lot of trial and error (with mental health services) and you have to set up lots of follow-up appointments,” said DeBroux. “That in itself can be very challenging for families who struggle with financial issues. It puts them at a greater disadvantage. Some parents, although they don’t like to, can do some services out of pocket, but obviously, that’s not ideal.”

Wisconsin children need someone trustworthy to listen to them, a difficult task for overworked educators

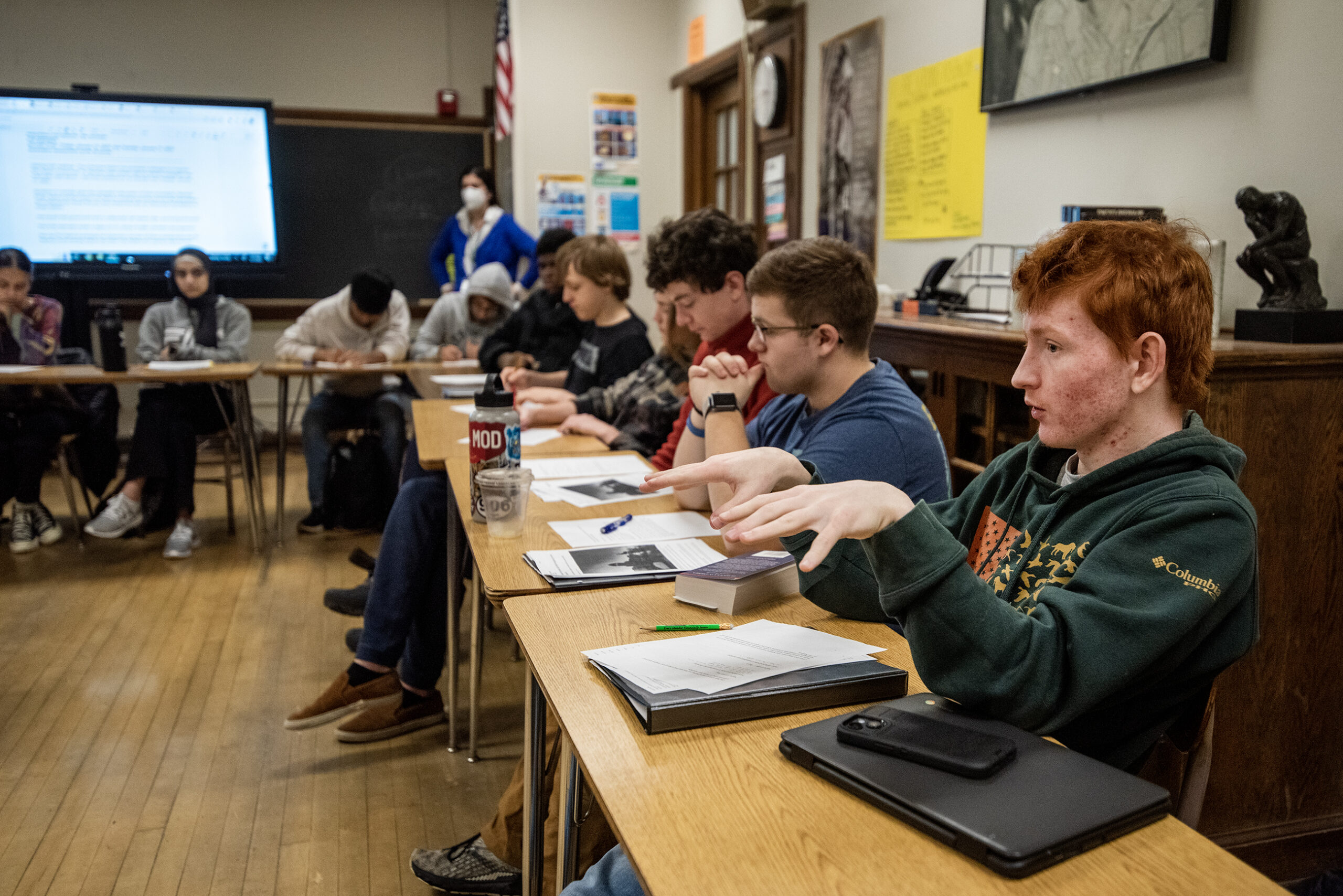

The alarming needs of youths were further driven home in the latest Youth Risk Behavior Survey from the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, which offered a distressing picture of what’s happening in high schools. The semi-annual state survey captures the health risks and mental health needs of students in grades 9 through 12.

In the most recent survey, from 2021, more than half of the students surveyed said they were anxious; 1 in 3 students said they felt sad or hopeless every day; 1 in 4 girls said they seriously considered suicide; and 1 in 5 students said they engaged in self-harm.

“Our kids are in trouble,” Hall said.

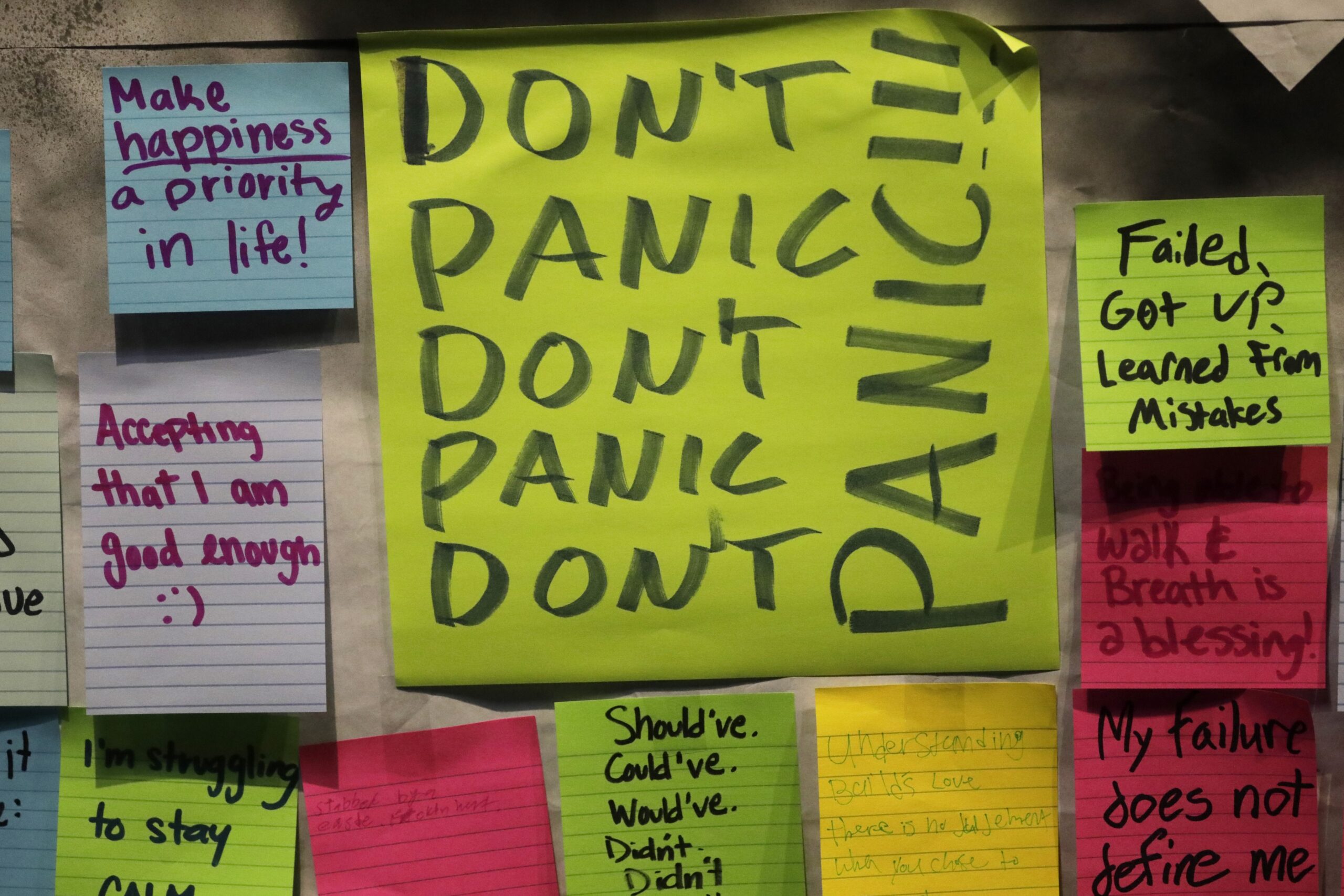

During the pandemic, the Wisconsin Office of Children’s Mental Health hosted a number of listening sessions to better understand what was lacking in students’ mental health. The prevailing response, according to Hall, boiled down to having a trustworthy adult with whom to have simple conversations.

That trustworthy adult, if it’s not a parent, often ends up being a teacher. But that can be an unfair load.

The overwhelming number of kids in crisis has challenged teachers’ more than ever to detect when a student needs mental health support.

Laura Jackson, executive director of student services for the Appleton School District, said the increased conversations about mental health awareness have been good, but it can leave school personnel with empathy fatigue — an inability to relate to, and care for, others as a result of emotional exhaustion and being overwhelmed by the needs.

“People in education care — that’s why they’re in this role. They care deeply about others and their success,” Jackson said. “But as people are struggling, that amount of care and compassion that you’re extending, is also exhausting.”

It matters where in Wisconsin your child experiences mental health conditions

Some schools are finding creative solutions to address the shortage of mental health care providers. Still, others are falling behind.

Jennie Garceau, executive director of student services for the Howard-Suamico School District, said it has full-time counselors at every school, including elementary school, and its larger schools have multiple full-time counselors.

Through partnerships with Connections for Mental Wellness, a Brown County behavioral health initiative that serves as a consortium for public schools, the district can enlist the help of licensed counselors from nearby agencies to support students — regardless of insurance coverage — in elementary and middle schools with greater mental health needs, Garceau said.

Howard-Suamico has also introduced a new 24/7/365 resource called Care Solace, which operates similarly to school social workers: providing counseling care coordination services for students, staff, and families completely free of charge.

School social workers, who often coordinate with families to get students the right care, are often overtaxed as they spend their days playing phone tag with parents and health providers on top of responding to student needs, Garceau said.

That’s a sentiment that extends beyond Howard-Suamico. Hall said social workers across the state are bearing the brunt of shortages, and not just in their own field. In order to coordinate with families, the right counselor needs to be available, an effort that is only growing more cumbersome.

And while school districts like Howard-Suamico are finding numerous resources, it’s a completely different story for rural schools in the state.

Kimberley Welk, a licensed marriage and family therapist in Green Bay, works with eight rural school districts in northeastern Wisconsin, including Kiel, Manitowoc, Oconto, Lena, Gresham, Tigerton, Laona and Goodman. She said that she’s never seen higher levels of trauma throughout every district she works in, on top of rampant levels of anxiety and depression.

Welk, who runs a school-based mental health program through her family therapist center, mixes telehealth and occasional on-site visits to schools to make up for what can be a two-hour drive.

Although Welk and her team of counselors can spot such red flag behaviors and address them, educators are finding themselves awkwardly trying to balance teaching with emotional support at levels that are unheard of, she said.

It isn’t uncommon for schools to contract with mental health providers like Welk. The dearth of providers, however, means that some schools won’t match up with the requirements set by the provider, said Rebecca Rockhill, executive director of Connections for Mental Wellness.

Connections for Mental Wellness, for example, has counselors for outside agencies in all nine school districts in Brown County, but only 24 out of 86 public schools. That’s due to there being only eight mental health providers who have the capacity to work with students in a school-based setting.

Working with students who are uninsured or one-third of students who rely on Medicaid tends to be a “tremendous income drain” for providers, Rockhill said.

Training staff to be more aware of mental health needs requires additional resources.

That’s a problem for many rural districts. Fewer staff members at rural schools have the knowledge necessary to write grants toward mental health programs that can bring in support systems like Care Solace, Hall said, which further adds to barriers to a population already struggling with isolation.

Two agencies recently declined to return to school-based counseling at the start of the 2022 school year, a result of being financially constrained. Because of this last-minute change, Rockhill said those schools had to scramble to find other therapists. Students, meanwhile, lost providers with whom they’d established trust, a foremost staple of effective talk therapy.

“We are completely taxed providing for schools right now,” Rockhill said. “We just can’t get into another school.”

Solutions are slow, but schools and area specialists are getting creative

Owing to her personal history, DeBroux joined NAMI Fox Valley in 2018 — “NAMI” stands for National Alliance on Mental Illness — as a parent-peer advocate and is subcontracted to work with the Little Chute Area School District and Menasha Joint School District.

She works as an advocate for parents, using her lived experiences to be an empathetic listener and compiling resources for families.

She talks every day with parents, either getting new parents “plugged in” to the system or working with recurrent parents on what’s best for their children. Stigma comes up in certain communities, DeBroux said, and she’s found that the best way to address stigma is to walk parents through her own story. That’s the key principle of peer advocacy.

“Peer advocacy is a big piece of this: Being able to share some of your story, to let people know they’re not alone,” DeBroux said. “I wish there had been a parent advocate when my family was navigating some of those things, because it can be very isolating.”

Some silver linings are slowly revealing themselves.

Universities across the state are beginning the process of embedding their school psychology graduate students into local public schools. That’s the case for the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which is using a new $6 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education to recruit and train 24 new school psychology graduate students, with an emphasis on students of color, into Madison’s public schools over the course of five years.

Elsewhere, the Medical College of Wisconsin is addressing the children and adolescent psychiatry shortage by extending its psychiatry fellowship program to UW-Green Bay, with the hope of embedding more new professionals in the region. According to Dr. Erica Arrington, the assistant professor and program director of the fellowship, about 80 percent of doctors-in-training will practice in the region within which they’re trained.

As it stands, one upshot of the pandemic is that young people have an increased sense of self-awareness, gratitude and resilience, according to a Wisconsin Voices study, conducted by the Wisconsin Institute for Public Policy and Service.

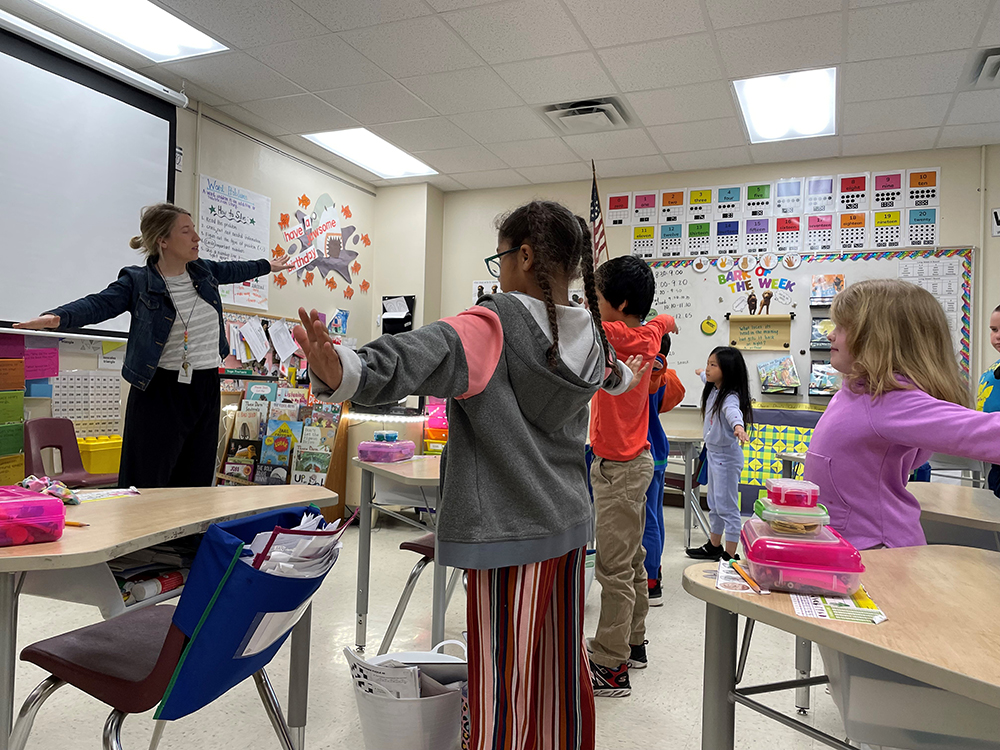

Frain and Liz Krubsack, another school mental health consultant for DPI, have been working to develop a comprehensive mental health program at schools across the state. One of the components they’re working to get into more schools is universal screenings for behavioral and mental health, which can help parents and educators identify health concerns early.

Therapy, Frain said, is only one piece of the puzzle. Educating teachers and staff on how to be more literate in the field of mental health is yet another piece, as is the emphasis on trauma-informed care.

Hall, meanwhile, emphasized the power of extracurricular activities, whether that means baseball or a book club, which contributes “very much” to mental well-being, she said.

And to address many of the Hispanic students in the state who tend to be family caregivers or work after school, Hall said more schools are adopting mid-day extracurriculars.

Hall said many educators and students are thinking creatively about how to cover ground that therapists cannot reach. These include mental health curriculums, capitalizing on the power of friends to get the right mental health resources, and arming peers, educators and staff with mental health training tools.

“Schools are a great place for us to work on (mental health) literacy. Kids are much less tied to stigma about mental health than their parents,” Hall said. “We have school staff and teachers saying, ‘This is even more important than academics right now and we would like the space to be able to work on this.’”

DeBroux emphasized the power of trust in working to address mental health in children and adolescents. It’s sometimes hard to know where to start, DeBroux said, and talking to other parents with similar life experiences empowered her to use her voice.

“A lot of times, for people who are struggling with behavioral and mental health challenges, it often feels like you are the only one who is going through this crisis,” DeBroux said. “It’s oftentimes a long, ongoing process. There’s no quick fix, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t hope for recovery and a good, healthy life.”

This story is part of the NEW (Northeastern Wisconsin) News Lab’s fourth series, “Families Matter.” The lab is a partnership between Green Bay Press-Gazette, Appleton Post-Crescent, Wisconsin Public Radio (WPR), Wisconsin Watch, The Press Times and FoxValley365. What would help improve the lives of Northeast Wisconsin families? This is one of the questions the lab hopes to answer. Write to the lab at families@wisconsinwatch.org or call 608-262-3642 and leave a message with your name, what you’re calling about and phone number.

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert.

If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text “Hopeline” to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.