A growing number of Wisconsin school districts are adopting Stop the Bleed kits and training. But experts say the cost of the equipment and some skepticism continue to be barriers to getting the kits in schools.

The School District of the Menomonie Area is one of the latest in the state to add bleeding control kits, which include medical equipment like a tourniquet and gauze which can be used to treat someone who is severely bleeding. Ramie McMahon, the district’s student health services coordinator, said the supplies arrived at the district’s schools this week.

McMahon said the district first had a Stop the Bleed class for staff in 2018, but the pre-made kits designed for schools were too expensive. She said Menomonie Fire Department Captain Matt Poliak raised money from local businesses to purchase the supplies this summer and the district has continued to work with the fire department to provide training on how to use the kits.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

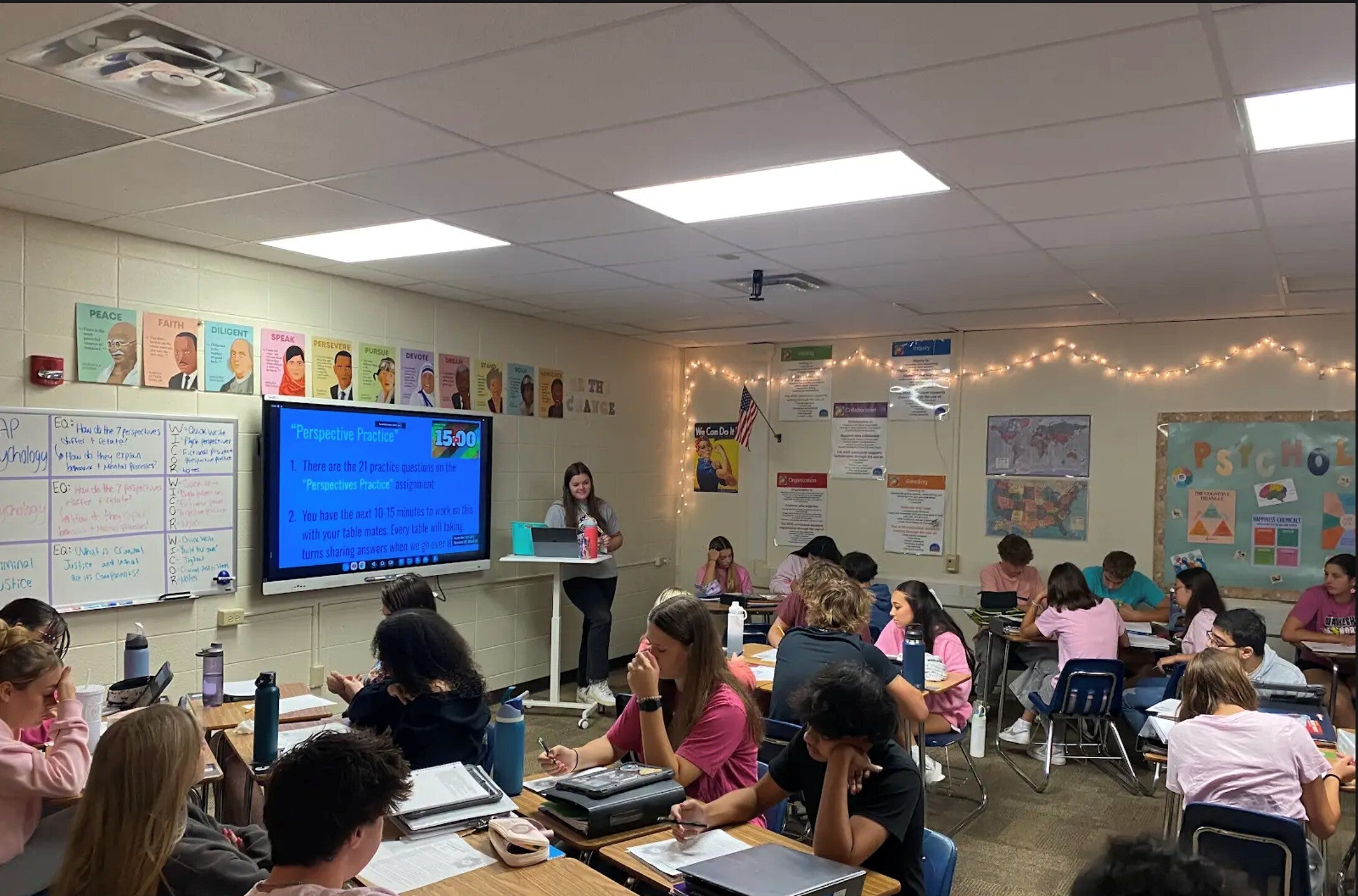

“We already had some staff training in August at our professional development day,” McMahon said. “Matt has been going to the health classes at the high school, so all the freshmen are getting the Stop the Bleed class.”

Tom Wohlleber, executive director of the Wisconsin School Safety Coordinators Association, said Stop the Bleed programs have been catching on at schools in the state in recent years, including in smaller, rural districts.

“Oftentimes the response is delayed because of the location of emergency responders related to the schools,” he said. “If they experience a violent event and their school staff and potentially students have been trained on bleeding control, they can save some lives.”

National efforts to improve bystander intervention during a bleeding emergency started in 2015, inspired in part by the 2012 mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. But Wohlleber said schools need to be ready to respond to many types of accidents that could involve profuse bleeding, like an injury from woodworking equipment in shop class or a student falling.

He said it’s taken time for many schools to come around to the program, not only because of the cost but also from not wanting to ask more of teachers.

“Just getting staff and students over that fear factor — being afraid of having to step in and help an injured person or persons — that clearly is one of the barriers,” Wohlleber said. “We come across in some schools or some communities that there’s this feeling that, ‘This won’t happen here in our community, so why should we go through with training all these people on something that may not occur here?’”

He said that sentiment has declined in recent years as the number of mass shootings in the U.S. continues to rise, and many districts are turning to grants or local service organizations to help get the programs funded.

Elizabeth Feisthammel, Sun Prairie Area School District nurse, said she sees the training as beneficial to students’ education. Her district first installed bleeding control kits in their schools in 2017, and has gone from training just student health staff to incorporating the information in all district staff’s CPR and first aid classes. She said many high school students are also receiving the training thanks to a grant received by one of the district’s students that provided kits for every high school classroom.

Fesithammel said a person can die from bleeding in minutes and bystander action can make a big difference.

“There’s lots of different possibilities where someone may experience severe bleeding,” she said. “It might be at school, but it might be in the community. So getting these skills to students now might help them in a situation in the future.”

Feisthammel said school staff have used the kits for two different incidents involving students in the last six years. She declined to give further details to protect student privacy, but said applying tourniquets from the kits led to better outcomes in both situations.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.