Wearing the vest was not a problem for Amanda Thoma’s 1-year-old daughter, Mia. The problem was it attracted the attention of her 2-year-old brother, Tucker.

“He was very curious,” Thoma said. “He did try to take her recorder out and press the buttons.”

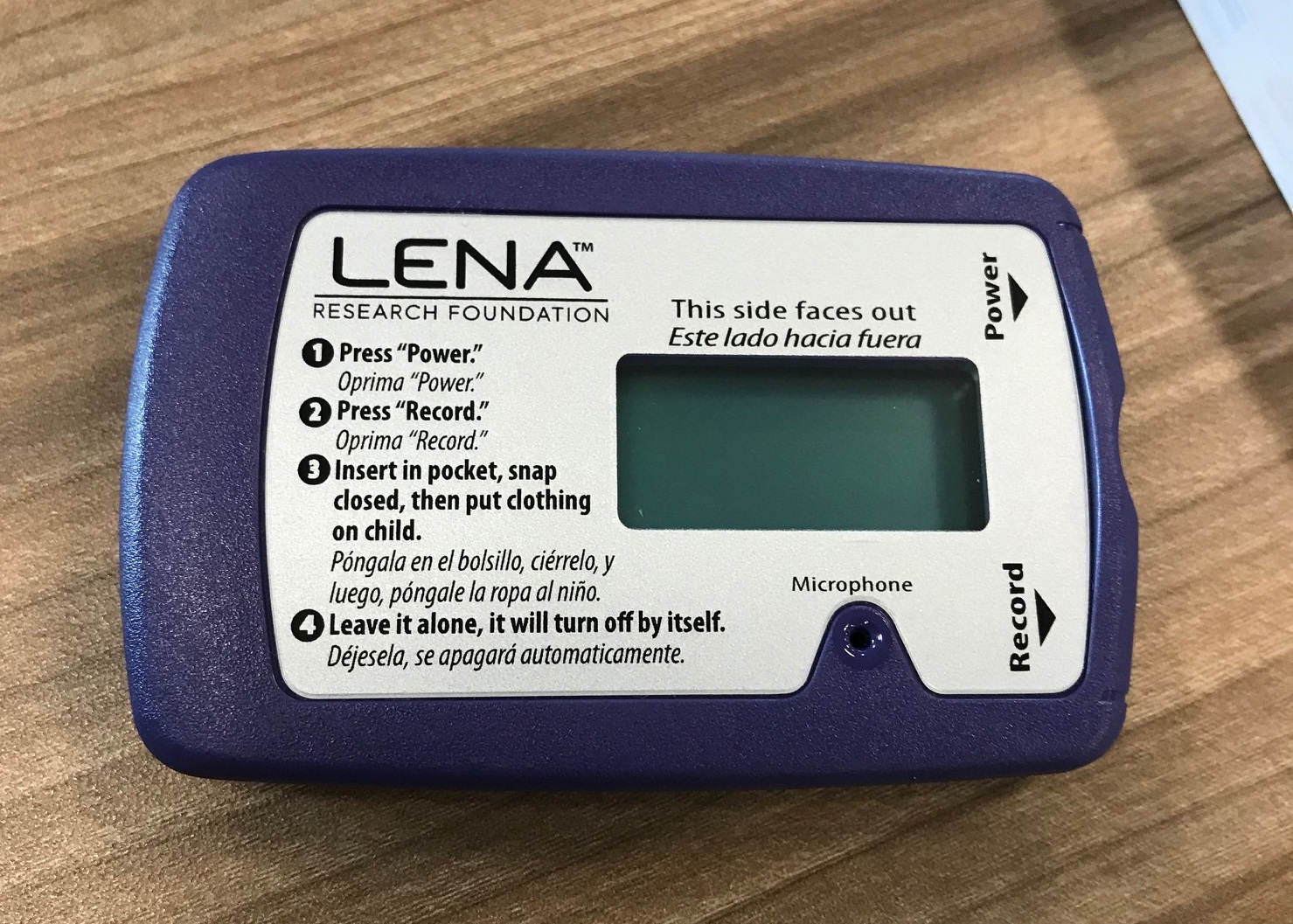

The recorder Tucker was after was the LENA Start device Mia wore one day a week all summer. It fits in the vest that Mia wore all day, and recorded all the words she heard and conversations she had with her mom and other adults, plus the amount of time she was exposed to TV or other electronic media. It’s all part of a nonprofit program that uses advanced technology designed to help encourage parents to talk to their babies.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Thoma is a fourth-grade teacher in Wausau. She signed up for the summer course to hold herself accountable, she said, and “make sure I’m talking to my littlest one as much as I talked to my first one.”

The data she got back in her LENA reports was fascinating.

Mia only has a few words — “mama,” “dada,” “dog” and “Tucker” — so most of their conversations involve “a lot of baby gibberish and babble,” Thoma said.

But they were conversations. The device recorded an above-average number of conversational turns in their interactions. The latest research in early childhood development suggests those back-and-forth interactions are especially important to a baby’s brain development.

As for Tucker’s curiosity, the solution was pretty simple. Thoma gave him his own vest to wear on the days when his sister had her’s on.

Thoma was part of a group of 10 moms who met for classes every Wednesday throughout the summer at the Marathon County Public Library in Wausau. This particular group was all moms, but it’s open to anyone and other LENA classes have included dads, too.

There are five LENA sites in Marathon County, and it’s the only program in Wisconsin that’s bringing the technology directly to parents. The nonprofit effort is supported by grant funding that makes the program free to parents.

LENA stands for “Language ENvironment Analysis.”

Classes involve the application of “talking tips” and a curriculum created by the Colorado-based nonprofit that owns the technology. It started out at the Wisconsin Rapids-based educational technology company Renaissance Learning Inc., before being spun off into the LENA Research Foundation, now based in Boulder, Colorado. There are also LENA programs geared specifically for teachers, day cares or Head Start programs. They’re active in more than 14 states so far.

And the program is growing in Wisconsin, too. The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee is piloting a program; others in Winnebago County are exploring options for starting one there. In Marathon County, LENA classes will also be held out of the library in Edgar — the first rural site for the local program — starting this week.

The recorders are designed to be lightweight enough for babies to easily wear them and sensitive enough to pick up nearby sounds. But what makes the technology special is its ability to analyze the sound data that comes back. No one “listens” to the data and none of the participants’ personal conversations are stored anywhere. But LENA’s programming is sophisticated enough to be able to analyze differences in the sound data to recognize and tally when a child speaks and an adult responds (and vice versa), and to distinguish that from the sound of a television, of another child in the room and of ambient conversations between adults. That data, advocates say, helps make parents conscious of the importance and the value of talking with their kids.

In Wausau, the program grew out of a group of nonprofits and public agencies called the Early Years Coalition, which came together in recent years to try to emphasize the short- and long-term benefits of boosting early childhood education efforts.

Dr. Corrie Norrbom is the program coordinator. She said launching a LENA program was a concrete way to advance that cause.

“This is something we can bite off and chew,” Norrbom said. “This is somewhere that we can actually give benefit to families, and use it as a platform to raise awareness as well.”

Socioeconomic Status Isn’t Key, But Talking Is

Tonya Wood is the mother of five children. She enrolled in the class to try to help her 2-year-old son, Cameron.

Cameron, who is the adopted son of Wood and her husband, was drug-dependent at birth, and he’s faced development challenges. He’s nonverbal, Wood said, and mostly just parrots the language he hears, as opposed to having words of his own. He uses sign language as well as a tablet to communicate.

Even without words, Cameron has spirit. During an interview, he took hold of a Wisconsin Public Radio reporter’s microphone and led the reporter on a brief chase through the library.

Wood said the LENA recorder did pick up conversational turns for him, and that it helped her to be conscious of interacting with him more.

“He’s starting to come up to us more and starting to show us his toys more,” Wood said. “He’s starting to interact with us more, whereas before he’d just kind of play in his own world. … We’ve seen more engagement with him since we’ve started this and started trying to talk to him more.”

And that, of course, is the point of the program.

Norrbom said she thinks the key is to let parents “know they have the power to make a huge difference in their baby’s brain development.”

A good message, she said, is that it doesn’t matter what challenges a family faces or what their socioeconomic status is.

“Just talk,” Norrbom said.

An influential study in the mid-1990s found children who grow up in poverty hear 30 million fewer words by the time they turn 3. More recent work has found flaws in that study, and suggests that the real “word gap” is much less — perhaps 4 million words or fewer. LENA technology is part of what allowed for the new, more precise research. The earlier study was based on notes taken by a researcher physically present in the room with families.

But one thing new research has reinforced is the value of conversational turns, and more broadly the importance of early childhood brain development. Researchers have shown a correlation between children’s vocabulary upon starting kindergarten and their success in later grades. The Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman has tracked the economic impact of early childhood education, finding it provides a consistently higher “return on investment” than other forms of social spending.

And regardless of socioeconomic status, parents tend to overestimate their own performance.

“People tend to not talk to their children as much as they think they do, and our data does support that,” said Nicole Tank, a prevention supervisor of family support programs for Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin. Tank led the LENA classes over the summer in Wausau. She said it’s an important component of the program that it isn’t restricted to low-income parents.

“We want it to be universal access, because everybody needs to learn this information,” she said.

Conversation Starts In Infancy

At the classes each week, participants reviewed their reports and talked about how they were incorporating talking tips with their kids. In the final class of the summer, they even held a “graduation,” dressing the kids up in mortarboards and LENA Start T-shirts. Adults’ shirts have LENA’s slogan, “Talk builds babies’ brains,” while the kids’ shirts say “Talk to me!”

Wood said Cameron’s bedtime routine had become smoother.

“We look forward to reading time,” she told the group.

Thoma said Mia, too, had become more likely to bring over a book for reading time. Several of the moms said they had trained themselves to slow down and wait for their baby’s answer — not just to talk at them, but to allow for back-and-forth exchanges. That back-and-forth can also be amusing, as in a video that went viral over the summer showing comedian DJ Pryor having an involved conversation with his babbling baby son about the season finale of the television show “Empire.”

The value of those interactions is the main message Tank hopes participants will learn, and spread to others.

“It’s just having those conversations, that back and forth conversation,” she said. “That should be done every day, all day, all the time. You build that skill from infancy, from the very first day they’re born.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.