For Christina Newman and her 6-year-old son Forrest, early December now means an unwelcome tradition — he was quarantined for a possible COVID-19 exposure last week, just like he was this time last year.

To get him back in school, he had to be asymptomatic and get a negative test in a health care setting — not an at-home rapid self-test, like the BinaxNOW tests that come in two-packs at local pharmacies — on day six or seven of his quarantine.

Like most children and adults, he’s no fan of the nasal swab tests. But Newman and her husband developed a strategy to make it easier.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“We pretty much discovered at home that if you either let him hold the swab, or you hold it with him and like coax him into sticking it up his nostrils, you can get him to do it, and he does a pretty good job,” she said. “He almost needs to have that autonomy to do it, because he doesn’t struggle as much.”

Newman was one of the parents who responded to WPR’s WHYsconsin asking how parents and caretakers are handling testing their children for COVID-19.

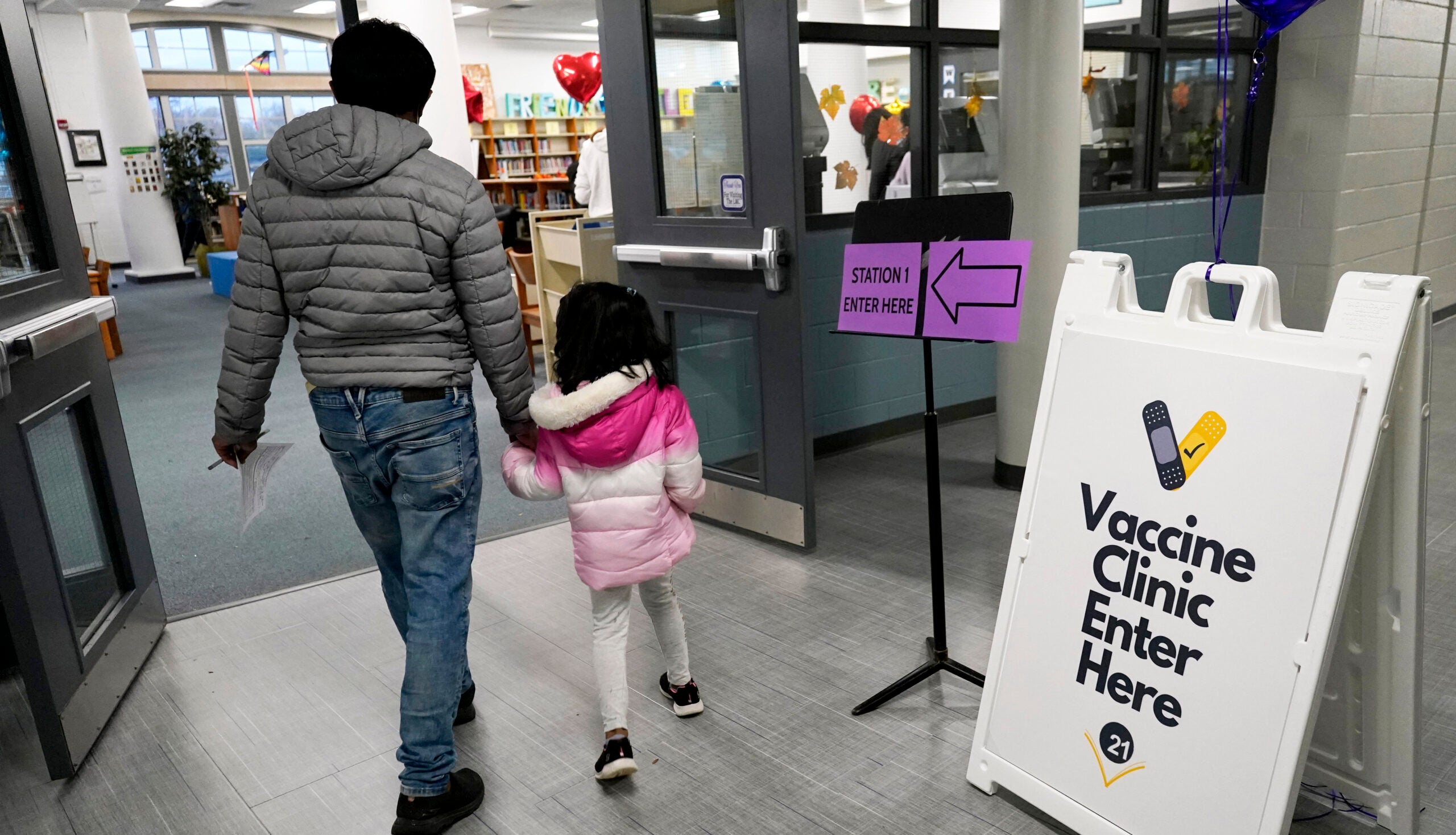

Forrest just got his second vaccine dose, which will cut down drastically on the amount of time he has to quarantine after a possible exposure — a welcome relief for Newman, whose family room has a giant blanket fort taking up the floor space and whose work can be frequently interrupted during the times Forrest has to stay home.

Still, they anticipate needing to get COVID-19 tests periodically to check whether sniffles are a cold or COVID-19, for example. The family mostly goes to a Walgreens nearby, or uses at-home rapid tests when they don’t need to meet the restrictions of a test to get out of quarantine.

While some of the mass testing sites around the state have closed or scaled down since the pandemic began, Wisconsin has expanded testing resources in schools — the state-sponsored school testing program is in about 75 percent of school districts around the state, and has done nearly 120,000 tests total, according to the state Department of Health Services.

Greg DeMuri is a pediatric epidemiologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who has also been advising the Madison Metropolitan School District on its testing program. He said it took some time to get the program up and running, but it’s starting to work well.

“It is very, very useful,” he said. “They are seeing cases there, and detecting cases, and they’re able to keep (sick) kids out of school because of it, so it’s a big asset to the schools and to the community.”

He said most of the schools participating in the state program do symptomatic testing or tests for possible exposure. Surveillance testing, which has come into play more in some school districts outside Wisconsin, tests a sample of children regularly to try to detect asymptomatic cases.

“There are a lot of difficulties, and the results are not all that encouraging,” he said. “You have to put a lot of money effort energy and logistics in it, and you’re not finding that many cases.”

He said he and other medical professionals are hoping more schools embrace “test-to-stay” testing, which is when a kid who’s exposed to COVID-19 is tested on a regular basis, allowing them to stay in school as long as their tests are negative.

“We’re all getting quite enthusiastic about the test-to-stay option,” he said.

Milwaukee mom Rebecca Silber, who also wrote in to WHYsconsin, loves the in-school testing program at her kids’ private school, which performs both antigen and PCR tests to kids for free, for any reason — so she can confirm that some sniffles are just allergies, for example, but also get some peace of mind before a visit to family.

“They’re really used to it,” she said of her ninth, sixth and first-grader. “I’m sure they don’t enjoy it, but it’s just kinda become part of the way of life.”

On weekends, though, when the school site is closed, it’s harder to find a place to get tested on short notice. She said she keeps some of the at-home rapid tests on hand, but at nearly $25 for a two-pack, it’s not practical to use them as often as she’d like.

“It makes me pause and kind of ration them out, the ones that I do have — like, is this worth the cost to test you for this, this time?” she said.

Even more frustrating is when she hears from her family in Ohio, where the state offers free rapid tests at public libraries.

“My parents live in Cincinnati, and my mom, she’s like, ‘Well can’t you just got to the library and get a test?’” she said. “It’s just kinda strange the way it’s set up here.”

Wisconsin’s free program mails tests to households who request them, and then have you mail the spit sample back in, which takes longer than the nasal swab at-home tests available in Ohio libraries.

The Biden administration recently pledged to distribute 50 million free at-home tests through libraries and clinics. It’s also said people with private health insurance will soon be able to apply to get costs for the tests reimbursed, though it isn’t clear how many tests may be reimbursable, or exactly what the criteria for reimbursement will be.

Although vaccination will ease the need for kids to be tested, the arrival of omicron and the ongoing delta variant surge means families will be thinking about testing, and COVID-19, for a while longer.

“I am hoping that as the weather warms up, since we are in Wisconsin, that we’ll be spending more time outside in the spring and that cases will go down again, like we saw last spring,” said Newman. “But I think we have a bit of time before that may happen, unfortunately.”