Wisconsin student attendance rates reached new lows after the pandemic, but the reason children aren’t going to school is complicated.

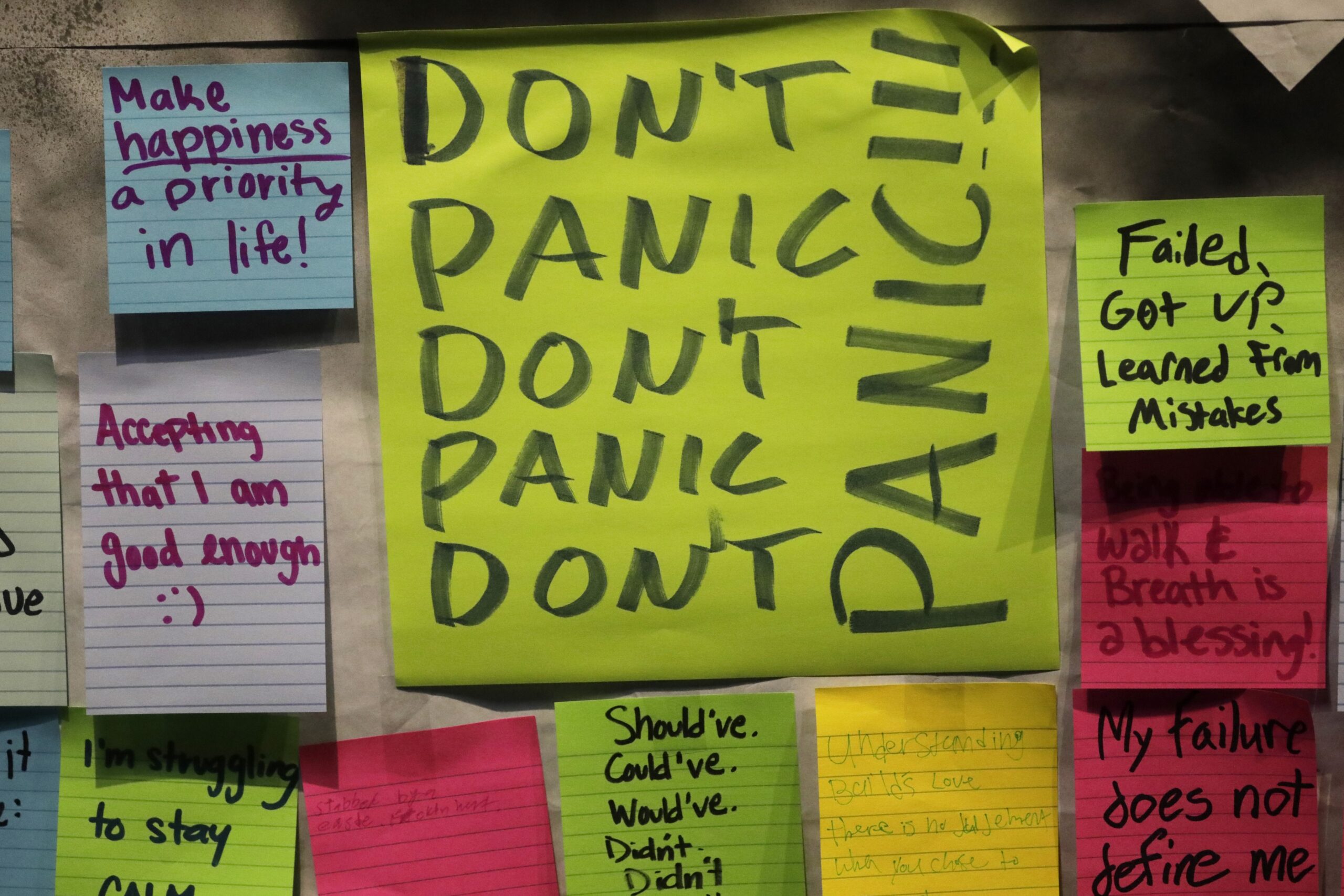

Mental health issues, housing instability and crime can all play a role in keeping students out of the classroom, said Nicole Cain, manager of social work and community services for Milwaukee Public Schools.

“When I look at our current data about students experiencing homelessness, we are definitely higher than we were during the pandemic and pre-pandemic,” Cain said. “And safety in the community, that’s a huge concern for parents. When there’s violence happening over the weekend, sending your kid to school on a Monday sometimes is really challenging.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

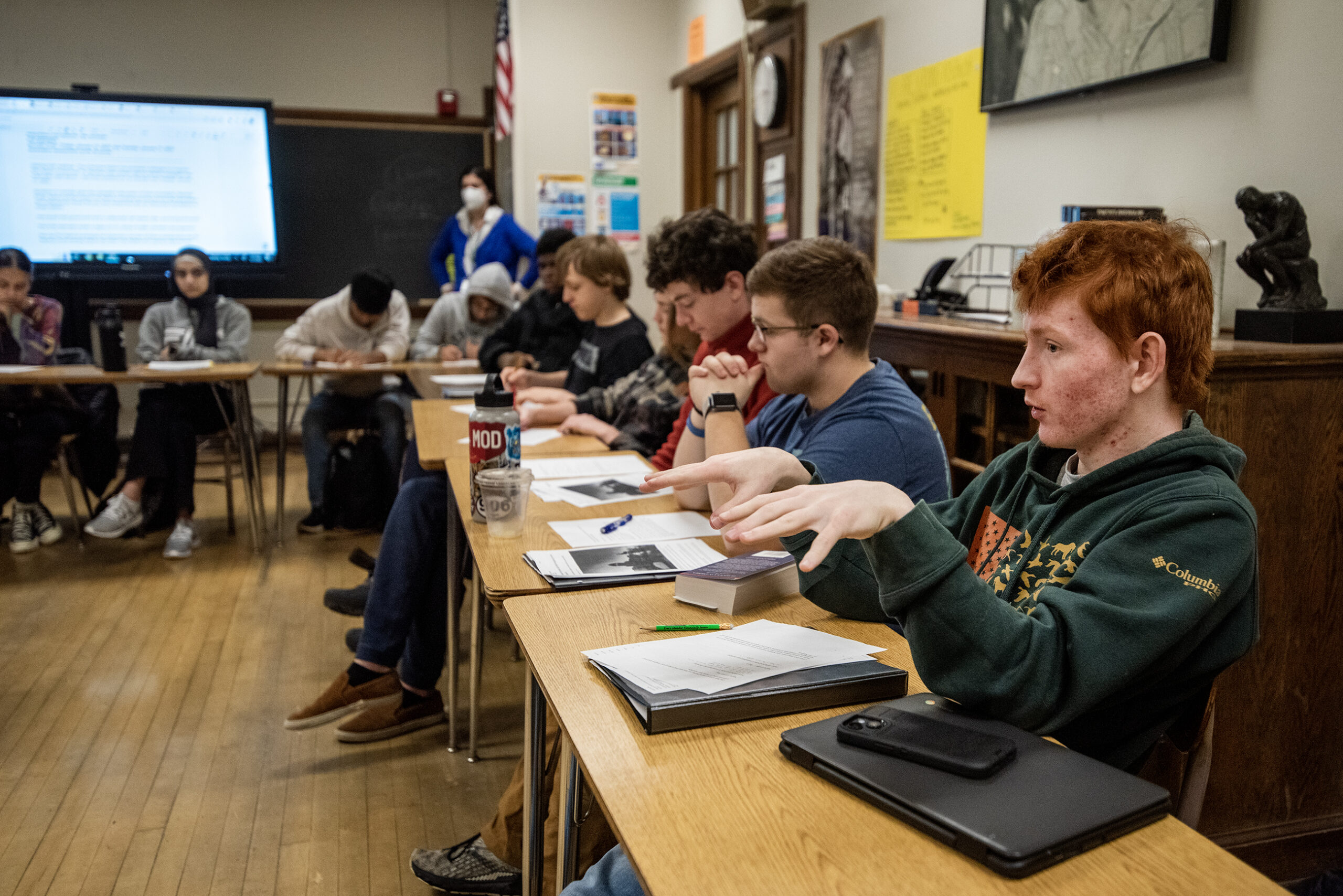

Cain testified Monday before the newly formed legislative truancy committee. The group is one of four bipartisan task forces Assembly Speaker Robin Vos created in August to gather data and make recommendations by the end of the year.

The state’s attendance rate reached a new low of 91 percent in the 2021-22 school year and nearly a quarter of students missed at least a month of school.

A student is considered chronically absent when they attend less than 90 percent of school days. The overall attendance rate for Wisconsin high school students was 89.7 percent.

Data from the 2022-23 school year will be released in March 2024.

Cain said about 15.7 percent of students in MPS are chronically absent. She said the district has created a tiered approach to truancy. This includes district-wide messaging to families, attendance leaders in every school, flagging students for intervention, and reaching out to families when students have eight unexcused absences.

The truancy committee was asked by Vos to evaluate the current practices so parents and schools can be held accountable for student attendance. Committee members suggested ticketing parents who aren’t bringing their children to school.

But Cain told the group taking punitive action is probably not the best solution. She said there are liaisons in the district attorney’s office who are social workers. Those liaisons meet with parents to talk about why children aren’t in school.

“I think the goal is to try to be more restorative,” Cain said. “I don’t think you necessarily want to charge a parent with truancy because you have been homeless, or you haven’t had a phone to contact the school. Or other situations related to poverty or just life situations that we are currently encountering.”

Department of Public Instruction best practice standards also say youth justice system involvement should be a “last resort.”

“Truancy is a symptom of youth needs, not future delinquency,” the guidelines state. “Harsh sanctions have been found to increase the incidence of truancy.”

State Rep. Patrick Snyder, R- Schofield, asked Cain if there was anything the legislature could do to help MPS with its truancy issues.

Cain said the district has clinical therapists in 39 of its 156 schools. Every year she has to write grants or find private money to keep those people on staff.

“I’d love to be able to have this opportunity for all of those schools,” Cain said. “If we just had funding coming into our district automatically geared toward school-based mental health, that would be very helpful.”

Gov. Tony Evers’ included more than $270 million to expand mental health services in schools in his budget, but the funding was cut.

In his budget veto message, Evers restored $30 million to continue funding for a program called “Get Kids Ahead,” which helps schools provide mental health services to students through community partnerships.

During Monday’s hearing, Dr. Lawrence Hoffman with Milwaukee Inner-city Congregations Allied for Hope, told the committee that research shows threatening parents is not an effective way to get parents to bring their children to school.

“Speaking as a mentor of low-income children in Milwaukee, I personally observe that visits and counseling by social workers and psychologists would probably make a positive difference,” Hoffman said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.