A report by the Education Law Center released this week found that school districts in Wisconsin are shifting more financial resources to special education as state reimbursements rates fail to keep up with increasing costs.

“In general, what we see is schools need more funding than they’re getting,” said Mary McKillip, co-author of the report.

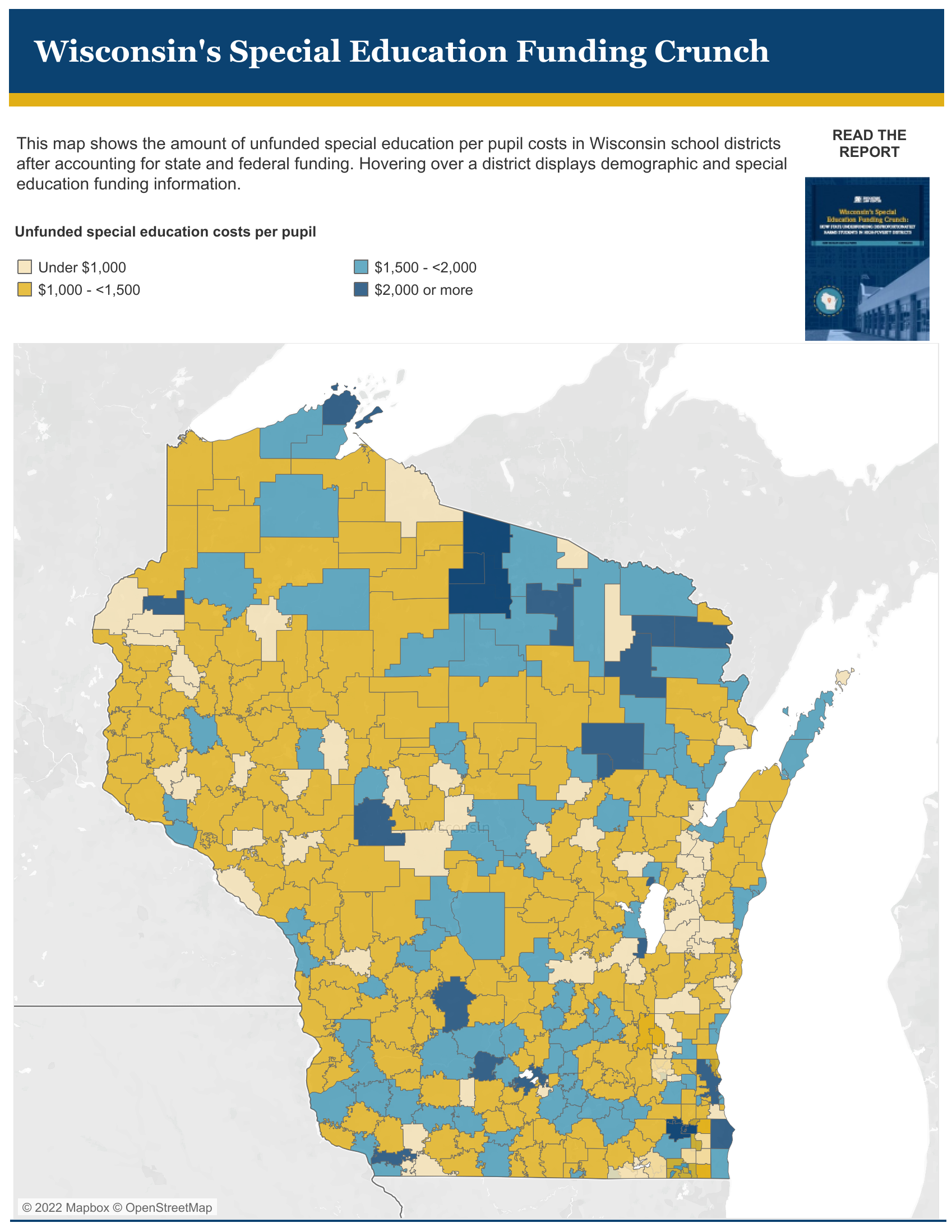

School districts in Wisconsin are covering $1.25 billion in special education costs beyond funds reimbursed from the state. The districts’ money comes from their general funds serving all students.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

School districts are required by federal law to provide special education services for students with disabilities. Districts are required to provide plans to meet the individual needs of those students, with accommodations that could range from specialized therapy, to adaptive technology, to one-on-one aides.

Students with disabilities represent between 10 to 15 percent of the student body in more than half of Wisconsin public schools, according to a Wisconsin Policy Forum report.

Over the last four decades, the cost of special education services has steadily increased. School districts spent $161 million on special education during the 1980-1981 school year. By the 2020-2021 school year, spending rose to $1.6 billion.

At the same time, the state cut back on the percentage of those costs it reimbursed. Forty years ago, the state reimbursed about 67 percent of the cost of special education services. But that reimbursement rate declined steadily over the following decades to a low of 24 percent in the 2017-2018 school year. Last school year, the reimbursement rate increased slightly to 30 percent.

Researchers McKillip and Danielle Farrie wrote that an increase in the reimbursement rate would free up money for schools to better support students, especially those from low-income families.

“The state is giving (school districts) the reimbursement of a fraction of the cost that they’re spending for special education, and then limiting the ways in which they can raise revenue to compensate for that,” said Farrie, a research director at the Education Law Center.

For Martha Siravo, co-founder of Madtown Mammas and Disability Advocates, the report hit a nerve. She is a wheelchair user and a mother to a 10-year-old who has received special education services since 2015. Her daughter has cerebral palsy and epilepsy.

“I am very outspoken. And I still find myself going into situations … why are we treating some of our students as less than?” she said.

At her daughter’s school, Siravo said, there is no accessible playground, leaving children with physical disabilities without a safe place to play. “But what if the school had money to add their own playground?”

Costs create extra burdens for high-poverty, rural school districts

The report also found schools in high-poverty areas must divert more money from their general funding. Those with 60 percent or more of their students as low-income took about $1,818 from their general fund per pupil, while districts with less than 20 percent of low-income students took $1,266 per pupil.

“When we underfund special education, we’re also underfunding the rest of our learners as well,” said Tom McCarthy, executive director for the Office of the State Superintendent.

“If we fund those students with disabilities, the whole system will benefit. It’s kind of a classic policy issue that we talk about in that targeting our populations of greatest need generally rises all boats,” McCarthy continued.

McKillip said increasing state reimbursement rates would free district resources.

“The more funding going in, the more that takes the burden off of the school districts with their general funding,” McKillip said.

Other states face economic challenges with school funding. But McCarthy said Wisconsin has left a legacy “of not funding schools to keep pace with inflation.” He said state lawmakers are not the only ones at fault.

“I think there is some blame to be cast also into our federal partners who have not recognized the changing need and the changing costs over time, and not increased the amount of funding available to states to meet this guarantee,” McCarthy said.

“We’ve just not given schools that inflationary need that they face every year, and they’ve been pinching pennies,” he said.

McKillip said part of the problem is that the state is not adding new money to account for the rise in costs.

“I think it’s something where sometimes you get sort of stuck in that status quo of, ‘Well, this is what we put in last year, so this is how much funding we’ll put in this year.’ But that’s not serving the special education students of today,” McKillip said.

Siravo agreed that “it’s almost become normalized.” But she said she’s hopeful for a better future for students like her daughter.

“What would blossom on the other side? I would love to see that because we’ve been at such a decline for so long,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.