One evening, Micki Boas came home to her son telling her he was called the Statue of Liberty in class because his hand was constantly in the air.

Her son has dyslexia, and he raised his hand whenever he needed help.

“Can you imagine, as a parent being told that your child isn’t getting the help they need and being bullied and called that?” Boas said.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Boas has been fighting for years for both of her sons, now ages 8 and 11, who have dyslexia, a type of learning disability that can lead to difficulty in reading comprehension and can impact the person’s interest in reading.

For her 11-year-old, Boas said it took four years, four lawyers and four schools to finally get him a formal diagnosis of dyslexia and the support that’s mandated by law.

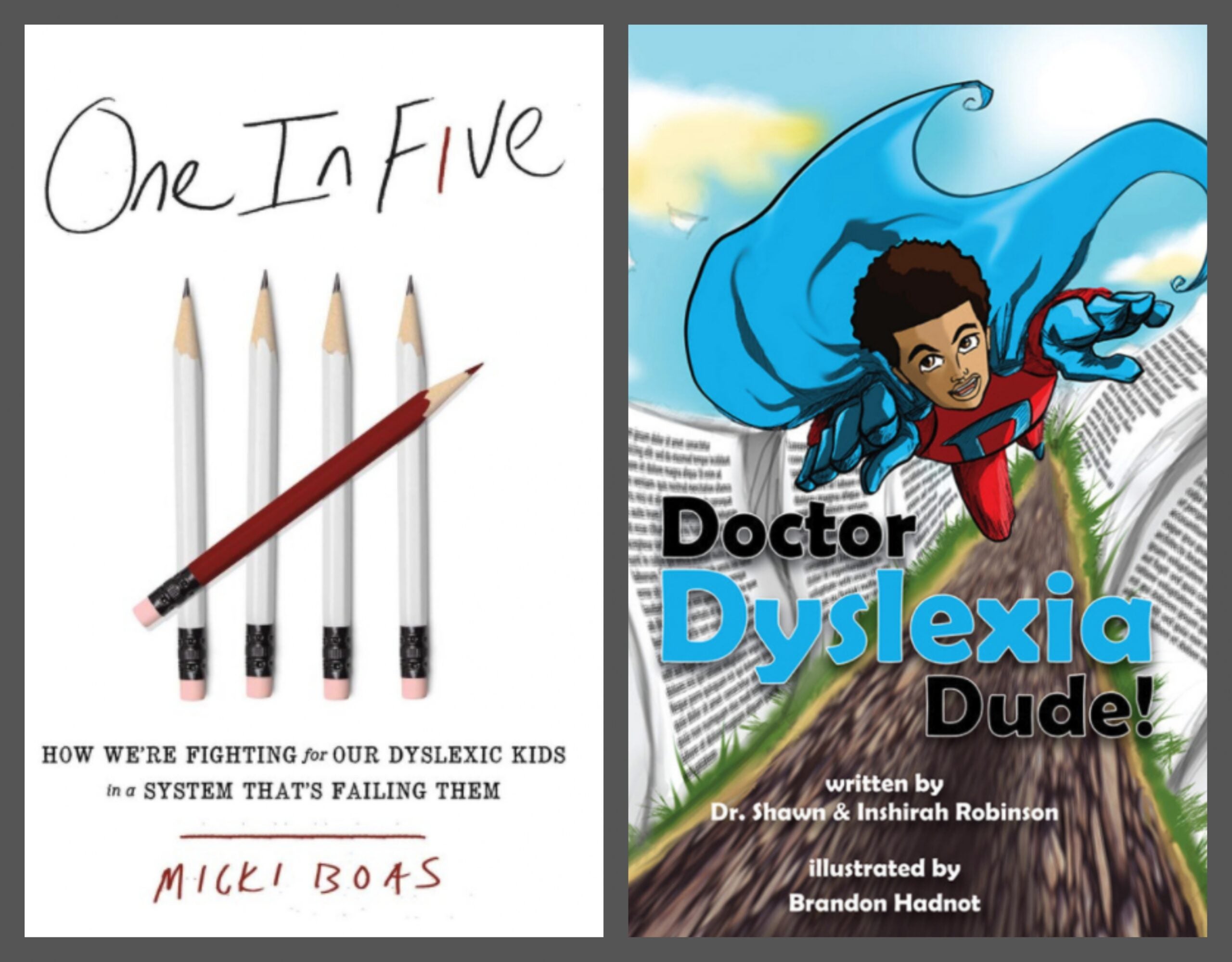

To help other parents navigate the confusing waters of a dyslexia diagnosis, Boas quit her job and wrote, “One in Five: Fighting for Our Dyslexic Kids,” published in August. The book features the stories of 20 parents of children with dyslexia, the struggles they’ve faced, and shortcuts that parents can use to help their children now.

Dyslexia is a genetic disability, meaning that a parent with dyslexia has a 50 percent chance of passing the disability to their children. People with dyslexia might have problems recognizing words, they may be poor spellers or they might have problems understanding how letters represent sounds.

“Most parents aren’t even diagnosed until they start seeing these difficulties in their child,” Boas said.

Dyslexic Diagnosis

Part of the problem, Boas said, is that children are being diagnosed with dyslexia too late. Oftentimes, they’re diagnosed around age 10, but the average child should be reading by age 7.

“You’re missing those critical years needed in order to support your child in the way that their brain learns,” she said.

But that gap between when they’re diagnosed and when they should have learned to read — called the discrepancy model — can have dire consequences for a child, Boas said. Their self-esteem drops, they might think they’re stupid, and they don’t want to go to school. Some drop out.

In fact, Boas said if a child isn’t reading by 3rd grade, they’re four times more likely to drop out of school.

Children can get diagnosed with dyslexia as early as age 5, and they can begin to show signs of the disability at age 3. A child may be dyslexic if they haven’t learned their alphabet, have trouble remembering their names or have difficulty remembering nursery rhymes.

The six early literacy milestones also are important to watch for signs of potential dyslexia. These include things like print motivation — whether the child is interested in books — understanding letters, building vocabularies and being able to manipulate sounds.

Boas said parents with concerns should speak openly with their child’s doctor about the issues they’re seeing. She advised that parents make sure to note that there is a family history of dyslexia, which will prove to be more helpful in getting the child help.

Parents can test themselves to see if they’re dyslexic by taking tests provided by the International Dyslexia Association.

Treating Dyslexia

The cause isn’t fully understood, but researchers think people with dyslexia have brains that develop and function differently from people who are neuro-typical.

Dyslexia can be treated in a variety of ways — and if it’s found early and is treated with support, a vast majority of those children, up to 92 percent, will read at grade level.

And even though dyslexic people rank themselves high in categories of problem solving, lateral thinking, creativity and art, 9 out of 10 say their disability has made them feel stupid, angry or embarrassed, according to a 2017 study from Made By Dyslexia.

That was the case for Shawn Robinson, an educator and author who lived frustrated and angry until, at 18 years old, he met a professor at UW-Oshkosh who diagnosed him with dyslexia.

“Once he taught me how to read, I just never looked back,” he said.

Now, Robinson is the author of the graphic novel Doctor Dyslexia Dude, which is about a Black superhero with dyslexia.

More Help

In addition to getting children with dyslexia individual help, Boas is advocating for parents and others to reach out to their representatives to foster changes to law.

She said that while laws were passed in 1975 to help children with disabilities, only about 15 percent of the special education funding needs are being met by the federal government. The rest of the funding comes from state and local districts.

Earlier this year, Wisconsin passed a law to create dyslexia guidebooks for school districts. Act 86 requires the state Department of Public Instruction to organize a task force charged with creating the guidebook, which would provide parents and others with answers to questions about dyslexia.

Although she lives in Jersey City, New Jersey, Boas said the problems related to dyslexia, such as underfunded programs, early intervention and teacher training, is a national issue. Oftentimes, teacher training programs are just not equipped to help children who have dyslexia, she said.

That’s the position that Robinson found himself in. Despite continued effort and support from his teachers, Robinson said they weren’t trained to provide him the instruction he needed in reading.

It was only after he started a weeks-long intensive remedial program when he was 18 with his UW-Oshkosh professor that he began to embrace reading and learning. And still, that wasn’t easy.

“It was hard,” he said. “I wanted to give up, I had depression. It was just a different experience. But I had people who just loved me and taught me the basics (of) linguistics, phonemes, graphemes, decoding and encoding and taught me how to use a dictionary.”

He had to relearn a lot of the K-12 standard curriculum, which he did while earning more degrees after high school. Robinson spent six years finishing his undergraduate degree, five years earning his master’s degree and seven years earning his doctorate.

His goal in creating the graphic novel is to give other kids like him hope.

“Let them see themselves in the sense of a superhero and overcoming their own odds,” he said. “Kids need that these days.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.