A national group working to reduce hunger says states need to do more to feed students when school is out for the summer.

The Food Research & Action Center says states are backsliding on progress made in feeding low-income children through summer meal programs run by schools, private nonprofits and local government agencies.

A report released Wednesday shows significant growth from 2011-2015. However, since then there’s been a decline: 5 percent in 2016, followed by a much smaller drop of a half percent in 2017.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The average daily participation in federally-funded summer meal programs in Wisconsin dropped 1.7 percent from July 2016 compared to July 2017, according to the report. That’s despite an increase in the number of sites serving meals.

“A lot of people associate schools as being the front line of (these meal sites) but the summer food service program is designed so that anyone can be a sponsor. So we reach out to the church communities, YMCAs and places where people are in the summer months,” said Thomas McCarthy, spokesman for the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

“We are continually putting in effort to try and locate sponsors. And we care deeply about trying to make sure there is not a drop off in summer months for students who need access to these meals,” McCarthy said.

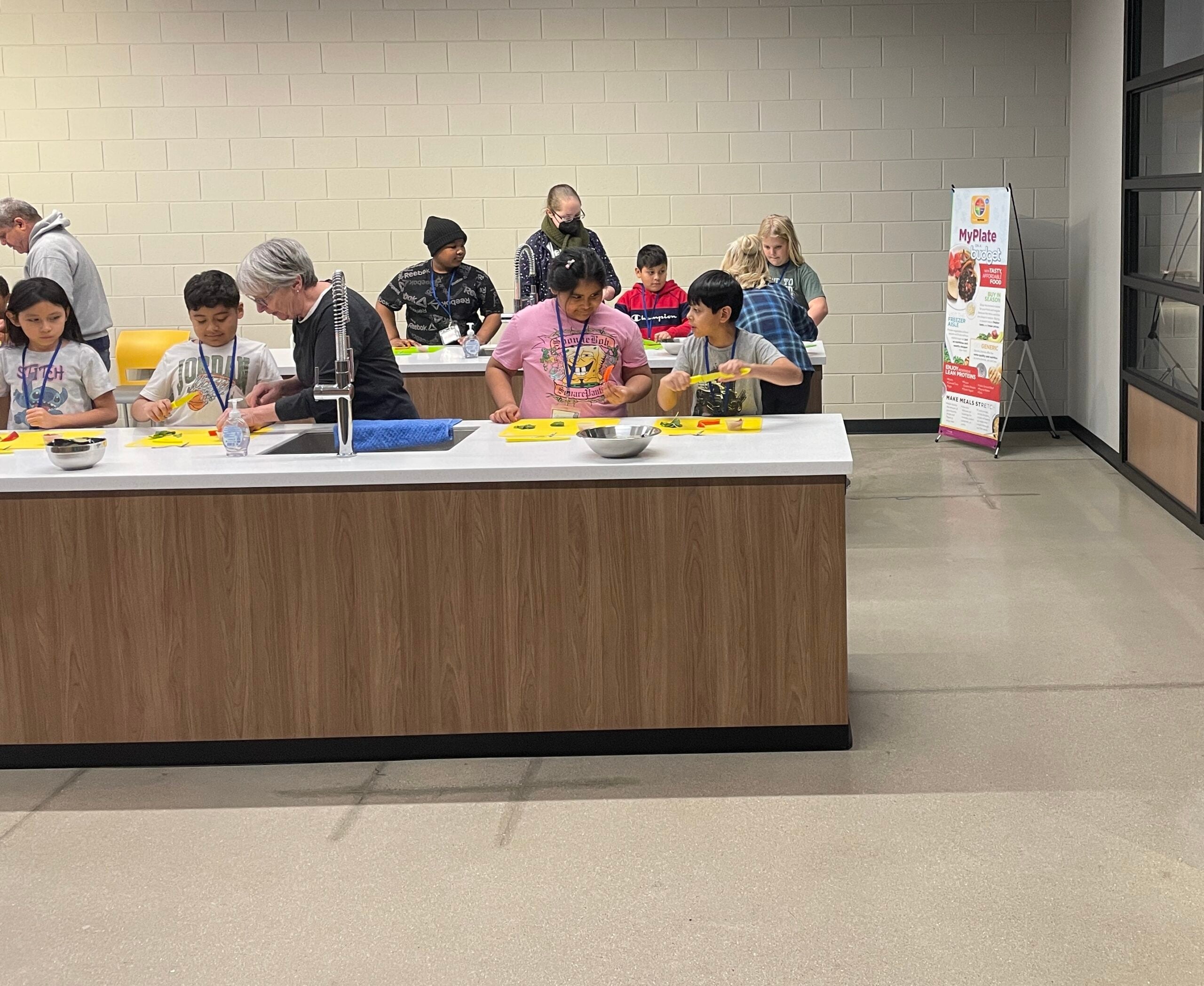

Summer meal sites around the country frequently combine educational programming with meals to promote continuous learning and prevent summer learning loss, or “summer slide.”

“Kids need summer meals and summer programs,” said Crystal FitzSimons, director of school and out-of-school time programs for the Food Research & Action Center.

“The great thing about the summer nutrition programs is that most of them are served in tandem with some kind of educational enrichment activity that keeps kids active, engaged and learning in the summer,” she said.

According to DPI, Wisconsin served 2.8 million summer meals at 888 sites in 2016 operated by 217 sponsoring organizations.

That compares to the more than 26 million children who eat school lunch every day when school is in session; about half of those students qualify for and eat free and reduced-price meals, DPI says.

Summer meal programs are focused on low-income children but the U.S. Department of Agriculture allows free meals to anyone 18 years old or younger. People up to 26 years old who are enrolled in an educational program for those with physical or mental disabilities may also receive meals.

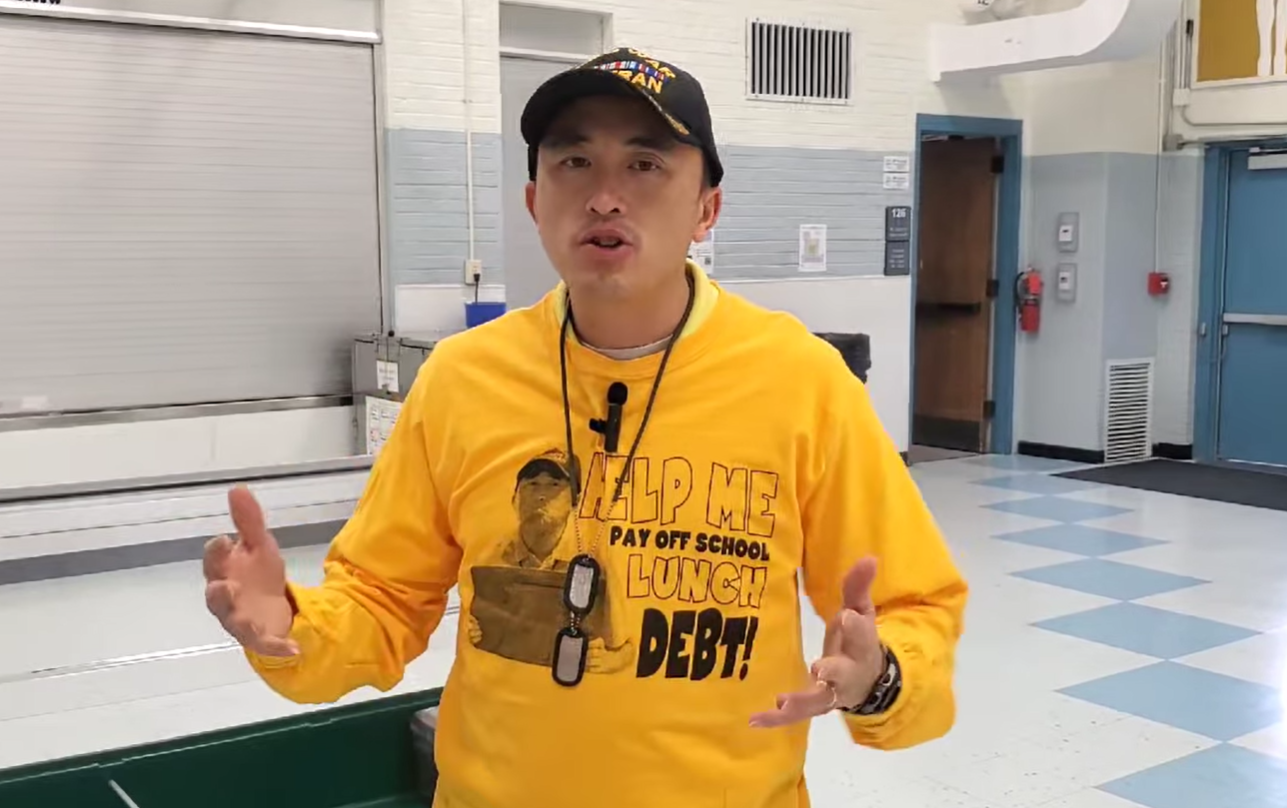

“They’re trying to take a little bit of the stigma out of essentially what amounts to poor kids line up over here to be fed,” said McCarthy. “I don’t think anybody wants to see that so they’re looking for creative solutions to that.”

Continuing student meals once school ends has been a concern for all states.

In summer, some states were able to provide summer meals to nearly half of those who receive free and reduced-price lunch during the school year; other states served less than 5 percent. Wisconsin fed summer meals to about 15 percent of those eligible for free and reduced-price lunches in 2016-17.

In order to expand access, the report recommends federal, state, and local government and private sources provide more funding for summer programming to help low-income children. The Food Research & Action Center also suggests Congress increase the number of communities eligible to participate in summer nutrition programs by easing paperwork requirements.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.