Despite weeks of pressure from public education advocates and schools, the biennial budget Gov. Tony Evers signed into law Thursday falls roughly $800 million short of the governor’s proposed K-12 education budget.

Advocates, including many who rallied at the state Capitol last month to urge legislators and Evers to put more money toward schools, wanted to see more funds directed to special education, higher revenue limits and increases in bilingual and bicultural education spending.

Under the new budget, the state will fund about 30 percent of eligible special education costs for districts — up from about 28 percent. Evers’ budget asked for the state to fund special education at 50 percent.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“Our budgeting process continues to pit children against each other,” said Green Bay Area Public Schools Superintendent Stephen Murley, whose district is 22 percent English language-learners and 14 percent students with disabilities.

“We do not fully fund special education, we do not fully fund English language-learner programs. We know those children have needs. As an educational institution, we’re committed to meeting those needs,” he continued. “The unfortunate part of that process is by meeting those needs, those dollars come out of our general fund, and that then makes it more difficult for us to meet the needs of our regular education students.”

The budget Evers signed into law doesn’t raise revenue limits, which set a cap on how much money schools can take in through a combination of state funds and local property taxes. If schools want to raise their revenue limits beyond what’s been set by the Legislature, they must take it to voters in a referendum — an increasingly common practice over the last decade.

“If we’re going to give schools money, we need to let them spend it,” said Heather DuBois Bourenane, director of the Wisconsin Public Education Network. “The tricks that the state Legislature is playing with the budget right now — providing an increase in aid but not raising revenue limits to allow districts to spend that aid — essentially just means we’re subsidizing a tax cut on the backs of our children in literally their hour of greatest need. That is absolutely unconscionable.”

The public education network and the Wisconsin Alliance for Excellent Schools released a statement calling on lawmakers to change the education budget before they adjourn, specifically to increase revenue limits, special education funding and equalization aid.

Evers did veto several portions of the budget, and at the signing ceremony Thursday, he announced schools would be receiving an additional $100 million in federal relief funds. After concerns that the initial Republican budget would not meet federal minimum spending requirements to receive $2.3 billion in relief funds, Republicans adjusted the budget to put a greater percentage of state funds toward education.

Evers cited the federal funds as the reason he did not veto the budget.

“At the end of the day, vetoing this budget in its entirety would have meant not only jeopardizing these investments but also likely causing our kids and our schools to lose $2.3 billion in federal funds when they need it the most,” he wrote in his veto note. “Leaving $2.3 billion up to the chance that Republicans — who took nearly 300 days to pass a second COVID-19 response bill during this pandemic — would come in and pass a meaningful budget in a timely fashion is not a risk I am willing to take for our kids or our schools.”

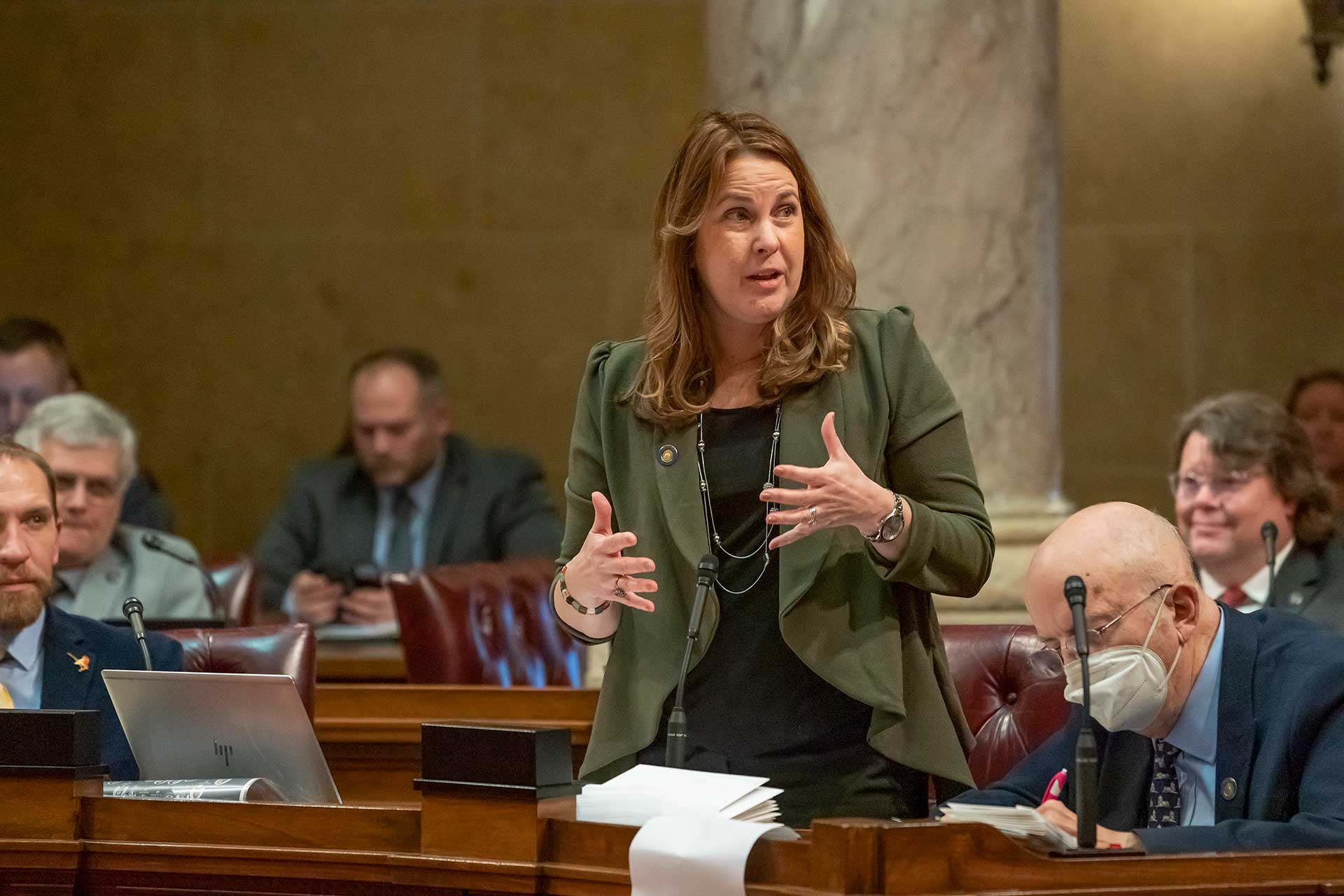

Sen. Duey Stroebel, R-Saukville, pushed back against Evers’ characterization of the budget in a statement Thursday, saying it meets schools’ needs.

“When the superintendent of public instruction distributes the federal COVID-19 education aid, all but a tiny fraction of affluent districts who refused to provide significant in-person instruction last year will receive a larger increase in total spendable dollars for education than they received last budget,” Stroebel said. “No matter how much money they get, no mater how many students they left behind by catering to their employees’ demands rather than students during the pandemic, too many school administrators think they are entitled to more money.”

For public education advocates, this biennial budget could have been an opportunity to close long-term inequities in Wisconsin’s education system. The state had a large budget surplus, and the difficulties of pandemic learning drew attention to the ways in which schools aren’t always equipped to meet their students’ needs. Some had floated the idea of overhauling Wisconsin’s education funding model so districts’ fortunes aren’t as tied to their local property tax base.

School administrators say the federal relief funds are no substitute for state spending increases. The federal money is one-time, which means it’s best used for infrastructure updates, purchasing new curricula, covering technology and cleaning costs from the past year and other pandemic-related expenses.

In an April resolution, the Wauwatosa School Board outlined its costs over the course of the pandemic, as well as the long-term effects of COVID-19 on students’ mental health and academic engagement, and called on state lawmakers to provide a predictable increase of $200 per pupil per year in state funding and in revenue limits. Wauwatosa estimated it would receive about $6 million in federal relief funds.

“The emergency federal funds will provide one-time recovery and relief, but will not enable the district to make progress on its strategic plan priorities,” the board wrote in its resolution.

Murley, in Green Bay, said staff — teachers, custodians, food service, educational aides — typically make up 75 to 85 percent of his budget.

“If we backfill costs relative to staffing with revenues that will not be in place when those federal relief dollars run out, we will have a funding cliff,” he said. “That will necessitate massive reductions in staff, which will then cause by ripple effect massive reductions in programs and educational opportunities for kids.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.