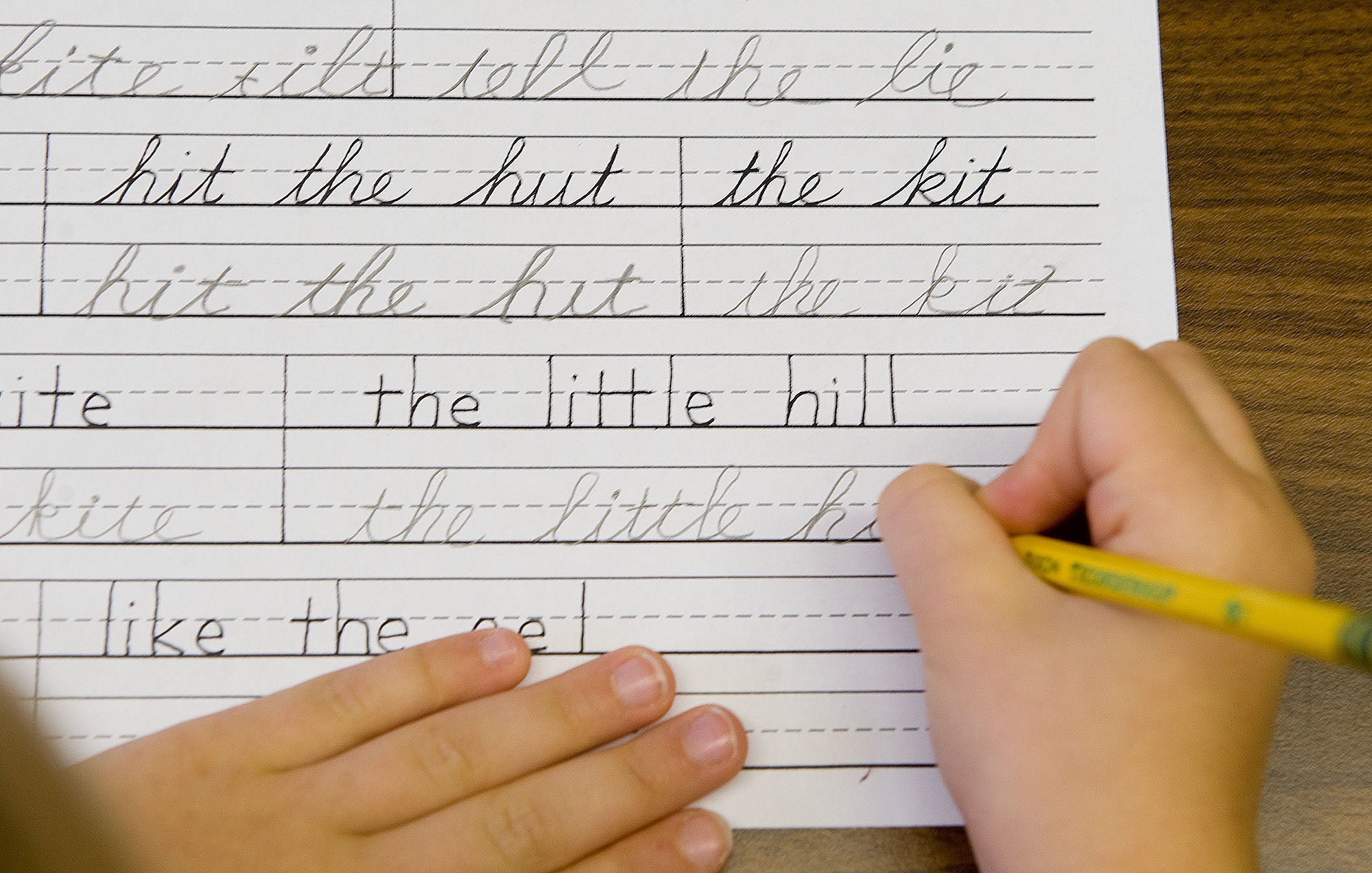

While keyboarding may be more practical for elementary school students to learn in the digital age, a state lawmaker says the benefits of learning cursive handwriting can’t be ignored.

“The process of writing cursive is better for young minds. It stretches their minds beyond the simple printing and certainly beyond the tapping of the keyboard,” said state Rep. Jeremy Thiesfeldt, R-Fond du Lac, the sponsor of a bill in the state Assembly that would mandate cursive handwriting in Wisconsin elementary schools.

“I’m not going to say there won’t be any challenge involved with this. You teach and you focus on what is important. I find by far the most important thing we do in school is teaching kids how to learn. In order to maximize potential of a young child’s brain we need to create those neurological pathways, and this is something that is effective in doing that and it really is rather inexpensive,” Thiesfeldt, a former teacher, said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Educators at two southwestern Wisconsin schools that still teach cursive starting in the second grade, agree with a lot of the arguments Thiesfeldt makes for teaching cursive to their students, but they also question the importance of mandating a course that they will likely never be tested on.

“We believe that there is still value with cursive in our culture. We want to be sure that we’re presenting students with the opportunities to have those skills as they move through our educational system,” said Rob Tyvoll, the supervisor of academic programs and staff development for the School District of La Crosse.

“There’s a strong sense that we’re moving toward the technological side of things. That communication and writing tends to take place more commonly now with keyboarding. I do think there are issues with not just instructional time, but what’s most relevant for students who are part of the new digital age,” he said.

The Tomah Area School District considered dropping cursive about 10 years ago when standards that drive what students need to learn for statewide testing were developed. Ultimately, educators in Tomah decided to keep cursive handwriting in the curriculum at eight elementary schools.

“It came primarily with the onset of the Common Core. Part of the discussion was the need to infuse more instruction for computers. Having students develop keyboarding proficiency so that they would be able to take the state assessment,” said Patricia Ellsworth, Tomah’s director of curriculum and instruction.

“It really came down to prioritizing what we need to cover, picking out what was most important to us. We value so many things we teach and didn’t want to see cursive go away, but we needed to find time to put in classes for technology at the elementary level,” she said.

The number of schools in Wisconsin who have removed cursive handwriting from their curriculum is difficult to estimate. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI) doesn’t keep track of that data, but Thiesfeldt estimates half of Wisconsin schools have dropped cursive handwriting from their curriculum. Ellsworth and Tyvoll said they are unaware of any schools in the La Crosse area that have ended teaching cursive.

While DPI doesn’t keep track of schools that do and don’t teach cursive, at a state Assembly public hearing on the topic earlier this month, it was revealed that DPI estimates it may cost several million dollars for elementary schools in Wisconsin to begin teaching cursive.

Thiesfeldt said he hasn’t talked with officials at DPI, the agency which sets state educational standards.

“When we talk about standards, this is often the work of our Department of Public Instruction,” Tyvoll said. “They’re the ones that we as school districts look to for direction around what standards we should be teaching. They give us advice about how we should form our curriculum. I think they really should have a powerful voice in this conversation.”

Thiesfeldt said he’s talked to a lot of educators at schools about the issue, and since it was raised it’s been well-received by both parties. He expects the Legislature to vote on the bill by early next year.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.