One day early in the school year, there was a lot going on in Lyssa Lauersdorf’s third and fourth grade math class at Johnson Creek Elementary School.

Some students were learning about fractions.

Another group was figuring out factors.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The room was busy, but quiet, with students moving from one task to another without any cues from Lauersdorf.

This is what a typical day looks like in this classroom and the others at Johnson Creek Elementary School. Students might have one short lesson as a whole class, then they rotate between working with Lauersdorf in small groups and practicing with a partner the new skills Lauersdorf just taught. Once the students are done with that, they move independently to working on other skills they’re learning at their own pace.

Lyssa Lauerdorf, a fourth grade teacher at Johnson Creek Elementary School, works with a small group of students on fractions at the beginning of the 2018 school year. Kyla Calvert Mason/WPR

Nine-year-old Derek Hernandez was doing some of that independent work that same day in September. He was looking at the online platform Johnson Creek uses to track students’ progress on the skills laid out in the state’s grade level standards.

“There’s pie charts and once one is all blue, that means I don’t need to work on it anymore,” he said of the pie charts that track the progress on meeting the required skills.

To keep turning those pie charts blue, Hernandez will choose another skill. He’ll watch videos and do practice problems until he’s confident enough to share his work with Lauersdorf. She’ll either sign off on the skill as completed or send him back for more practice.

Fourth-grader Derek Hernandez views his student proficiency plan in September 2018, the blue in each pie chart shows the portion of each skill level he has mastered, while red shows how much he has left to work on. Kyla Calvert Mason/WPR

Classroom curriculum like this, where work is tailored to students working at different paces or where they’re working independently at their own pace, is what’s known as personalized learning.

When school districts across the country responded to a survey about what kind of technology purchases they were planning on making this year, 90 percent said they were looking for tech to support personalized learning.

In Johnson Creek, the elementary and middle school students are in classes that are based more on the skills they’ve mastered than how old they are. The district is moving the high school in that direction, too.

The school district serves a village of nearly 3,000 people where new subdivisions back up to corn fields and farms. Part of the district’s move toward personalized learning was an interest in setting the town apart for something other than its location on Interstate-94 about halfway between Madison and Milwaukee, and it being home to an outlet mall, Johnson Creek Premium Outlets.

“The board really wanted to see our academics increase and they wanted Johnson Creek to be more than just an outlet mall, which, that is what our area is known for. So, now we’re getting to be known around the state and outside of the state as a place that meets students at their academic readiness,” said Lisa Krohn, the district’s director of teaching and learning.

Johnson Creek Middle School and High School building. Kyla Calvert Mason/WPR

Meeting students at their academic readiness means more than having them work on math problems online.

Dominique Patterson, 11, has been a student in Johnson Creek for three years. She said one of her favorite projects last year was working on her research skills.

“I did internet safety because it was what I wanted to do, like I could recommend different games to people that teach you about internet safety,” she said.

Having that kind of control over her work is different from what she remembers of her more traditional school.

“At my old school we had one thing that we all do,” Dominique said. “But now, when we finish our work, it’s not like you go on a website and are jotting down math problems. It’s like what you’re fascinated in, whatever you want to research.”

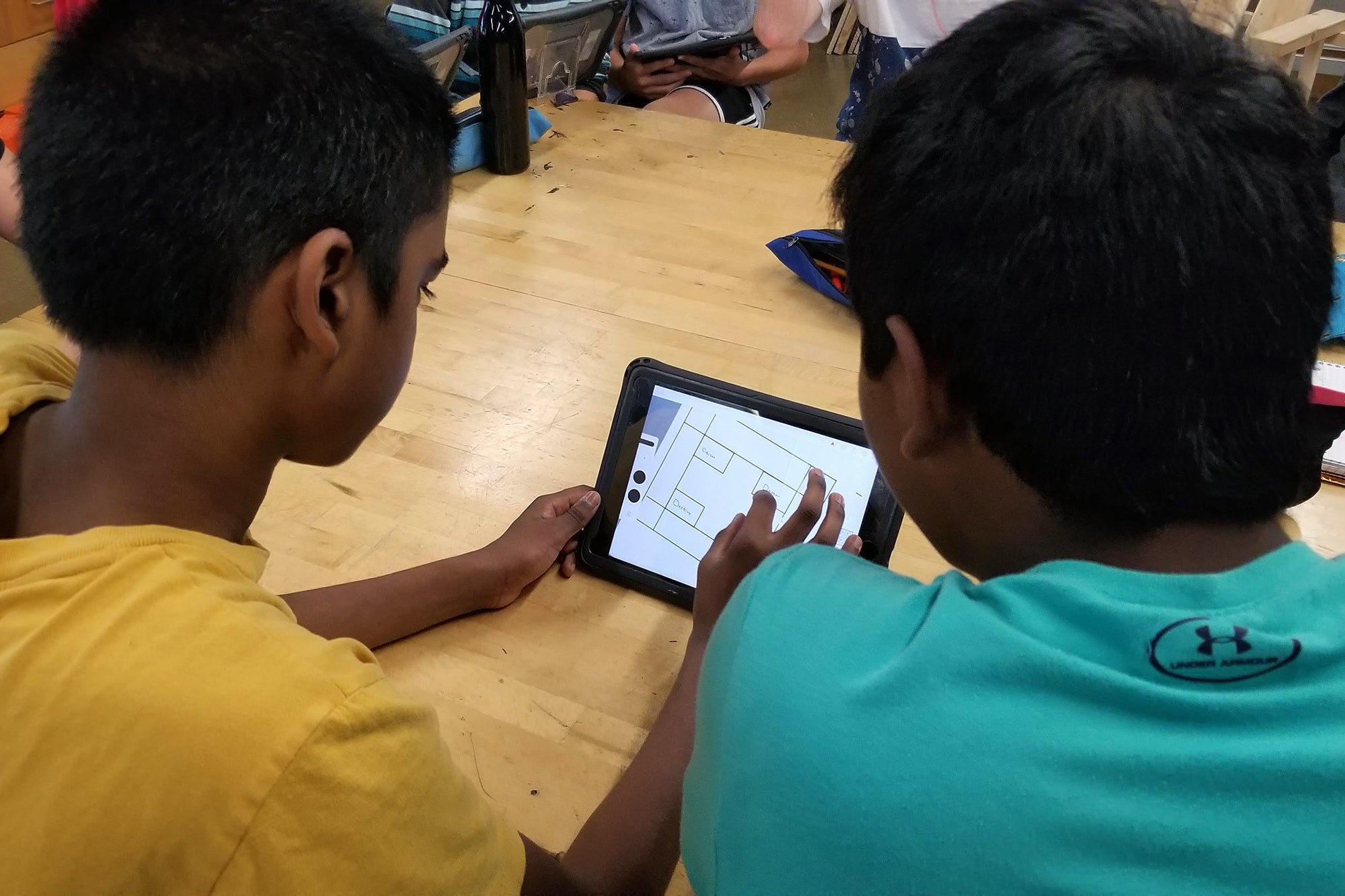

During an independent work session in September 2018, Lyssa Lauerdorf’s upper elementary students at Johnson Creek Elementary School work on assignments that cover in-class lessons or lessons they’ve chosen for themselves. Kyla Calvert Mason/WPR

But this isn’t the only way to do personalized learning. There is no one set of ideas or methods that is universal, many districts implement methods they’ve created and tailored to meet their goals, said Richard Halverson, a professor of educational leadership and policy analysis at at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who researches the use of technology in education.

“Some people think it’s the shape of the learning space, some people think it’s the use of computer adaptive learning tools, some people think it’s interest-driven learning,” he said.

He and his grad students have identified the common threads they see in schools that use their individual version of personalized learning with success.

“They turn around their whole classroom to try to figure out what do kids need and what do they want to learn? And then they organize instruction around that,” Halverson said.

Waukesha STEM Academy is a charter school in a suburb outside Milwaukee. Kyla Calvert Mason/WPR

About 30 miles from Johnson Creek in a Milwaukee suburb, another middle school built around personalized learning takes an approach where students spend less time in what looks like traditional classes and classrooms.

Outside of core courses, where students have opportunities to choose the books they might read or other ways they might fulfill some classroom assignments, students at Waukesha STEM Academy also take part in semester-long workshops. In one, the Toy and Game Design Workshop, the middle school’s students learn about design, marketing, research and more.

Earlier this year, Elizabeth Schulte was trying to decide between creating a video game based on the flora and fauna of a local nature preserve or a Legos-like city designing toy.

“I’m definitely going to try to do the Fox River one first, but if I can’t figure out how to do the programming, I’m going to have to do the city build one because we only have a limited amount of time and I have to figure out which one would be the wiser decision,” Elizabeth said.

Managing and planning her time is part of what she’s learning, and, if she chose the video game, she said it would mean one thing for sure: “I have to work extremely hard and take a lot of classes and learn a lot more than any other time.”

Elizabeth Schulte talks about the building blocks game she is proposing for Waukesha STEM Academy’s Toy and Game Design in September 2018 Seminar. Kyla Calvert Mason/WPR

Eighth-graders at Waukesha STEM Academy share presentations they’ve created about the nitrogen, carbon and water cycles in their high school level biology course.Kyla Calvert Mason/WPR

Amy Bigelow has a daughter at Waukesha STEM Academy. She said the way the school pairs personalization with projects like this has turned around how she feels about school. Bigelow remembered afternoons during elementary school.

“She would come home from school just in a funk at the end of the day,” Bigelow said of her 12-year-old daughter in sixth grade.

But that has changed.

“She came home the first week and she said, ‘Mom, I didn’t realize I’m learning, but it doesn’t feel like I’m learning.’”

Enthusiasm and student independence are the kinds of outcomes personalized learning advocates tout.

In September 2018, students talked about their plans for designing a natural disaster resilient city in a Waukesha STEM Academy Seminar. Kyla Calvert Mason/WPR

Krohn of Johnson Creek and James Murray, the principal at Waukesha STEM Academy, each said the schools have many students working on material that’s well ahead of their age-based grade level. They also said the approach allows students who need more time with any given skill to slow down and really master it instead of being dragged along with a class that is moving on to more advanced material.

But researchers haven’t found that personalized learning leads to significant improvement in standardized test scores. Halverson said that could be because personalized learning is an effort to get away from teaching that is focused on standardized tests.

“Do we want young people who take control of their own learning and set their own path and can articulate their own goals? Do we want kids who can master standards and are proficient at standardized-based content? Do we want both?” Halverson said.

He said those are questions education policymakers are grappling with. Whether more schools embrace personalized learning could depend on their answers.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.