By next year, Wisconsin schools will have to change the way they’re teaching children to learn to read.

A sweeping bipartisan bill signed into law this summer will shift schools from what has been known as “balanced literacy” to the “science of reading” approach.

But data shows that most teacher education programs at colleges and universities are still not fully teaching the science of reading.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

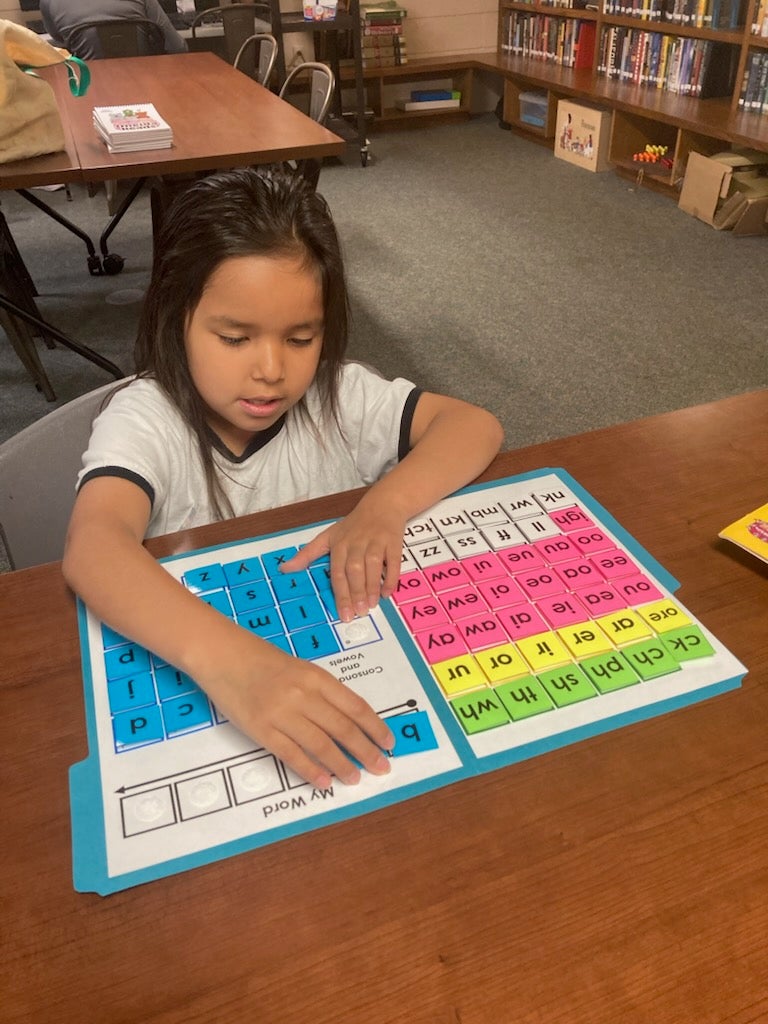

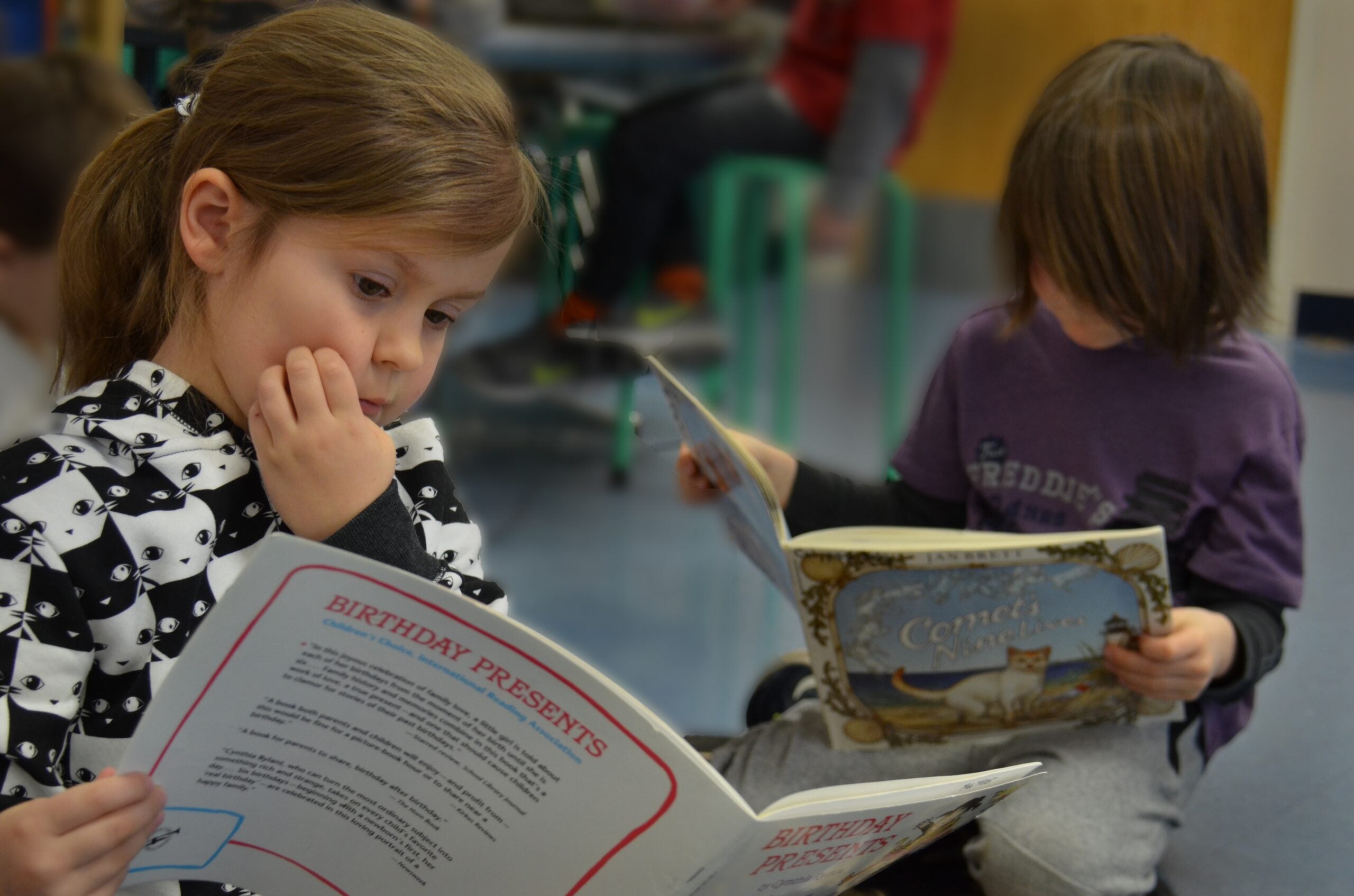

Instead of learning how to read through pictures, word cues and memorization, children will be taught using a phonics-based method that focuses on sounding out letters and phrases, with the hope of addressing the state’s lagging reading scores.

Wisconsin’s new reading law doesn’t explicitly tell the universities how to teach. But it will prohibit the Department of Public Instruction from approving teacher education programs unless they include science-based early literacy instruction and do not incorporate three-cueing — a model that emphasizes that skilled reading should include using meaning and sentence structure cues to read new words.

Wisconsin teachers who do not receive this training will not be eligible for a license beginning July 1, 2026.

“I do believe that the universities have been one of the major causes of the problems we see in reading,” said State Rep. Joel Kitchens, R- Sturgeon Bay, one of the lead authors on the reading legislation. “They now seem to be moving in the right direction, but change is hard.”

How Wisconsin’s Schools of Education are scoring

Tom Owenby, the associate dean for teacher education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said the reading bill demonstrates a renewed commitment to supporting students across Wisconsin in being able to read proficiently, which is a goal everyone shares.

Owenby said the School of Education has already undertaken “an intensive examination of its class syllabi, coursework, and fieldwork” to make sure it is aligned with International Literacy Association standards and is using the best, evidence-based practices.

“We are currently collaborating with K-12 partners to ensure that our teacher education students have opportunities to teach literacy and receive feedback on their practices multiple times during their preparation program,” Owenby said, adding that the school is awaiting further guidance from DPI.

This summer, the National Council on Teacher Quality, or NCTQ, examined nearly 700 schools of education programs, including 15 in Wisconsin.

The report looked for evidence that coursework for future elementary teachers includes five core components of scientifically based reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

The analysis found Wisconsin ranks above the national average for its colleges, having at least some of the five core components. But 10 of the 15 schools are still teaching techniques contrary to research-based practices that can inhibit the reading progress of many students, the report found.

The UW-Stevens Point ranked exemplarily. Maranatha Baptist University and UW-Madison received “A” grades. Four schools — Carthage College, UW-Milwaukee, UW-Superior and UW-Eau Claire — scored an “F.”

UW-Milwaukee did not respond to requests for comment.

“We’re in the midst of a long overdue revolution on the science of reading, but teacher prep programs haven’t fully caught up,” said Heather Peske, NCTQ president. “Prospective teachers—and certainly their students—deserve far better.”

Peske said it is helpful for teacher prep programs to shift to align with the science of reading that is now being taught in more elementary schools.

Colorado and Mississippi lawmakers have set standards so their teacher preparation programs meet all five core components of scientifically based reading instruction. Peske said she hopes more states set clear standards for what colleges should be doing to prepare aspiring teachers to teach reading.

“And provide them with the support in the form of capacity building, and also being very clear about the program review process and the accountability process and the consequences if they don’t improve,” Peske added.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.