Beth Mullen-Houser has a running Word document, currently six pages single-spaced, full of information about kids, the delta variant and COVID-19 vaccines.

Mullen-Houser, a La Crosse psychologist and mother of a 10 year old, has been anxiously reading through daily emails from Kaiser Health News and listening to podcasts about the latest COVID-19 research to try to figure out the best path forward for her son, who’s still too young to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

“The biggest place that I sit right now with all of this is that it’s so confusing,” she said. “There’s so much conflicting information, there’s so many really, really good experts that are saying different things, so it feels like as a parent I am wanting to do my own reading so I can come to my best guess of what is the right thing to do, at least for our family.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

She wrote into WPR’s WHYsconsin last spring — well before the FDA had approved any COVID-19 vaccines for emergency use — to ask whether an eventual vaccine would join the list of required shots for kids entering school and day care.

Vaccines are only available for kids ages 12 and up at this point, which leaves Mullen-Houser’s son out. After doing all of her research, she’s decided to keep him learning from home until he can get vaccinated.

“It’s his last year before he stars middle school, which means I desperately want to send him back,” she said. “But right away, and for our family, I think we’re making the decision not to until he gets vaccinated, because that’s so close.”

Recent estimates say the vaccine will be authorized for kids under 12 sometime in late fall or early winter. Even with the approval for kids 12 and up, though, younger Wisconsinites are lagging behind in getting vaccinated — about 30 percent of those 12 to 15 have completed their vaccination series, and about 40 percent of 16 to 17 year-olds, compared to about 50 percent of the total eligible population in the state.

Julie Willems Van Dijk, deputy secretary of the state Department of Health Services, said several factors play into those lower rates.

“First of all, they’ve had less time, they were not eligible for vaccine until May, whereas many others were eligible in January, February and March,” she said. “And parents are still learning more about this vaccine and may have further worries about their children.”

Willems Van Dijk said she’s also concerned about misinformation about vaccine side effects spreading among young people, particularly teenage girls.

Because the COVID-19 vaccine isn’t approved for younger children, and the approval for tweens and teens is still under an emergency use authorization, it’s still too early to say whether, and when, those immunizations would be added to the list of required vaccines for school and day cares.

Even if it were added, Wisconsin families can opt their kids out for medical reasons, a religious exemption or a personal belief exemption. The last category is the broadest and the most commonly used.

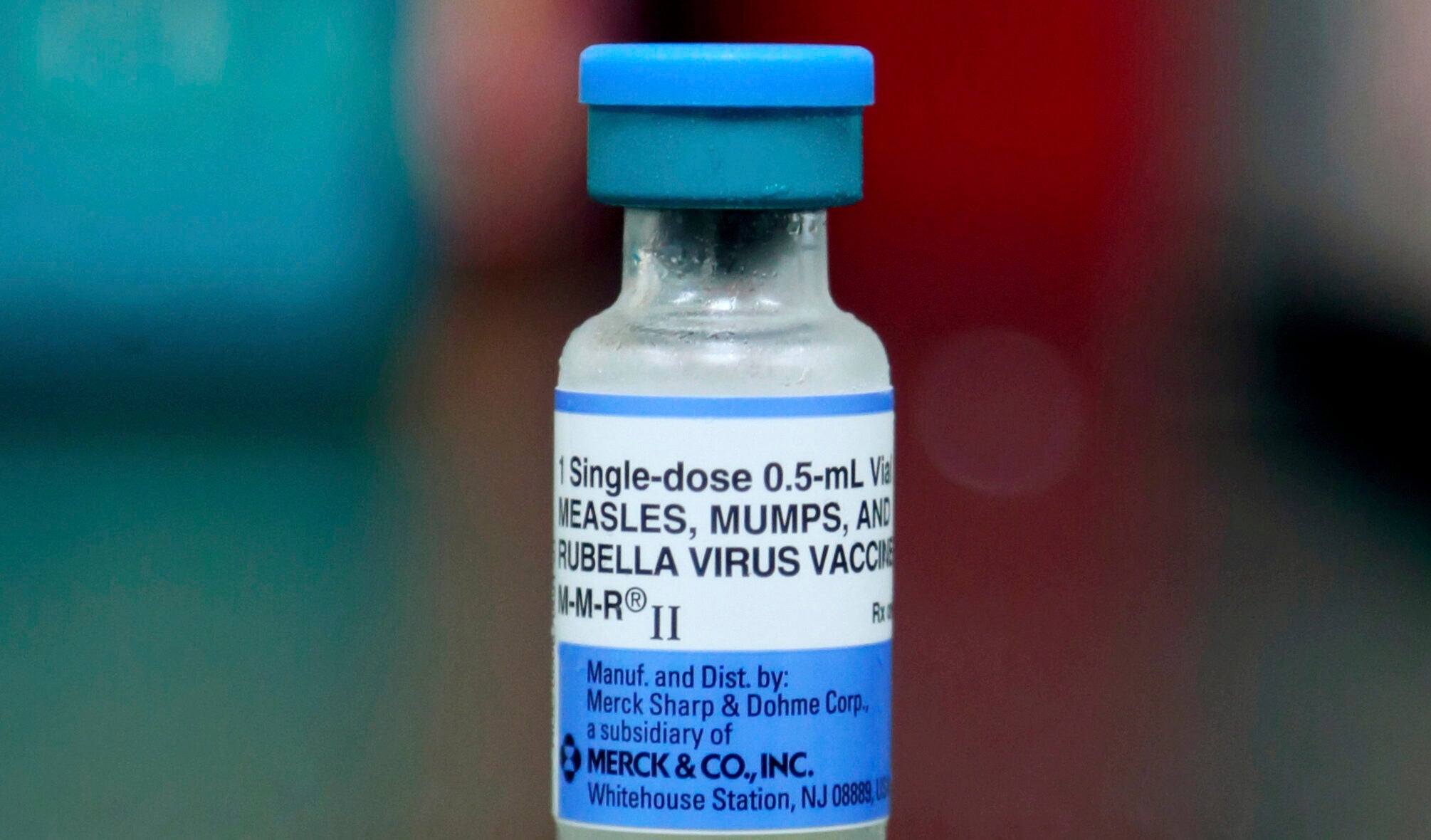

Wisconsin is now one of only 15 states with a personal belief exemption — other states have eliminated theirs. Washington, for example, closed that loophole for the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine in 2019 after a series of measles outbreaks.

Wisconsin lawmakers, including Democratic minority leader Gordon Hintz, attempted to end the personal conviction exemption in 2019, but were unsuccessful. With the spread of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation and the politicization of some public health measures, Hintz said he’s worried anti-vaccination sentiment has grown.

“Even with some of the vaccine reluctance we were seeing with measles and mumps and childhood vaccines that are required for education, we were still over 90 percent (vaccinated),” he said. “In this (COVID-19) case, it was adults having to think about something that was already political, you had people who didn’t believe in COVID, or were told it wasn’t serious or it was just the media, and so the vaccine discussion for some was just another part of that.”

Hintz said that makes him particularly frustrated, because the vaccine was remarkably effective at protecting people from contracting COVID-19 before the delta variant, and has led to far milder cases and fewer hospitalizations among the vaccinated who get breakthrough cases from the delta variant.

He’s also worried about the effects of COVID-19 vaccine skepticism on how families view other vaccines.

“I’m afraid that this has not been a positive for vaccines overall,” he said. “I do think the built-in resistance from the anti-vax or vaccine reluctant community has made things worse, and I’m afraid that more people have connected with them as a result of this. The normal vaccine debate that we had before COVID is more complicated now.”

Willems Van Dijk said Wisconsin is seeing delays in Wisconsin kids getting other childhood vaccinations, like MMR and diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis.

“I’m not ready to call it anti-vaxxing,” she said. “I think it’s largely because health care was disrupted during the pandemic, and children missed well-child appointments and missed getting their vaccines.”

Mullen-Houser, in La Crosse, said part of the reason she’s been compiling her COVID-19 research document has been to monitor whether getting her son vaccinated once he’s eligible would put him at risk. She said the thing that gave her the most pause was reports of myocarditis — heart inflammation — in some kids who got the vaccine. Still, the incidence was incredibly rare, and research seems to show kids recover quickly. And experts overwhelmingly recommended parents get their eligible kids the vaccine without hesitation.

“When I weigh — as so many parents are doing — the social, emotional, educational benefits of him being able to go back among his peers at school more quickly, I guess I feel that the risk balance is in favor of getting him vaccinated,” Mullen-Houser said.

Until then, Mullen-Houser said her family is very privileged to be able to keep her son learning remotely — both she and her husband work from home, and her job as a psychologist allows her to take on fewer clients to balance work and her son’s school. Still, as with so many things about the pandemic, she’s quick to point out that there aren’t any sure bets.

“We are making a best guess here, and we could be making a wrong guess. We’re also taking a chance with my son’s social and educational development,” she said. “I think he’s going to be fine. He’s a quick learner, but you know, for a lot of people there was a lot of harm keeping kids at home.”