With the beginning of the school year underway, teachers and administrators are looking for ways to reverse a likely decline in academic progress. But they’re also not putting too much stock in standardized tests.

“I think there’s a lot of celebration happening just with kids arriving for what we hope, desperately, to be the most normal school year in a long time,” said Kate Tesch, the Superior school district’s director of continuous improvement and assessment.

Recent data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress found a steep decline in math and reading test scores for 9-year-olds across the country. The test results show the largest average score decline in reading since 1990 and the first-ever drop in math scores.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The drop in test scores was most pronounced among students who faced the brunt of the pandemic — students of color and those from low-income families.

Peggy Wirtz-Olsen is a high school teacher and president of the Wisconsin Education Association Council, a public-sector trade union. She said those gaps have only worsened during the pandemic.

“The new scores show everyone really what educators have been shouting from the mountaintops for years stretching far before the pandemic,” Wirtz-Olsen said. “Opportunity gaps are expanding. And they’ve been multiplying not only due to COVID-19, but also to many politicians’ commitment to defunding our nation’s public schools.”

In Madison, it would cost more than $50 million to compensate for lost learning time, according to Edunomics Lab research data. That number more than doubles for the state’s largest district in Milwaukee.

“We’ve done amazing work, but our kids definitely have experienced something that we have no historical reference in our lifetime,” said Tesch. She emphasized that the Superior district is focusing on “supporting kids where they’re at.”

Pandemic disruptions and the ‘learning loss’ frame

Although the drop in test scores has raised alarms among educators, some are pushing back against the idea that the NAEP data — and standardized testing at large — paints a full picture.

Maxine McKinney de Royston, an associate professor in the Department of Curriculum Instruction at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said that tests were constructed as part of a system that has failed students of color. She also said tests aren’t completely predictive of future success.

“We use these tests to say, ‘Oh, now we’re in crisis,’ as opposed to saying, ‘Well, are we actually evaluating or assessing that which is important to us? Are we actually evaluating learning?” McKinney de Royston said.

Michael Jones, president of Madison Teachers Inc., also disputes the “learning loss” frame. He said it requires people to think of education in a static way without room for recognizing student potential.

“Unfortunately, that’s the message we give to kids who then internalize it and then look at themselves in a negative way without actually realizing all their genius,” he said.

Mental health worries mounting

As some people’s fears about students playing “catch-up” in their learning mount, many leaders are calling attention to the mental health challenges children and teachers are facing.

“We have kids who are grieving. We have kids who are missing. And there wasn’t a whole lot happening around attending to those social-emotional needs, much less to support students learning at home,” McKinney de Royston said.

Jones, with Madison’s teacher’s union, also said the bigger problem at hand is the disconnect students experienced during the pandemic.

“I see nothing in either any national publications nor in the NAEP or any standardized test that really connects to a child’s mental health, their ability, how they see the world, what they’re worried about, what they’re anxious about, what they want, what their dreams are,” he said, adding, “none of that factors into, ‘read this paragraph and tell me what the verb is.”

Paul Schley, superintendent and elementary school principal at the Cornell School District, echoed that view, saying it’s hard to quantify learning losses because it varies per student. In his eyes, poverty is at the heart of the issue, especially for students who didn’t have access to high-speed internet.

The percentage of Cornell Elementary students on free and reduced lunch assistance reaches nearly 70 percent, according to ElementarySchools.org statistics. Census Reporter data shows that 13.6 percent of people in the northwestern Wisconsin district fall below the poverty line, about 25 percent higher than the overall rate in Wisconsin. The school is about 45 minutes from Eau Claire and a half hour from Chippewa Falls.

Rethinking the education system

While the NAEP test results are raising alarms nationwide, some leaders in Wisconsin said they believe it’s time to rethink the education system.

McKinney de Royston said giving into the “learning loss narrative” at face value only adds more pressure in ways that are not supportive of learning.

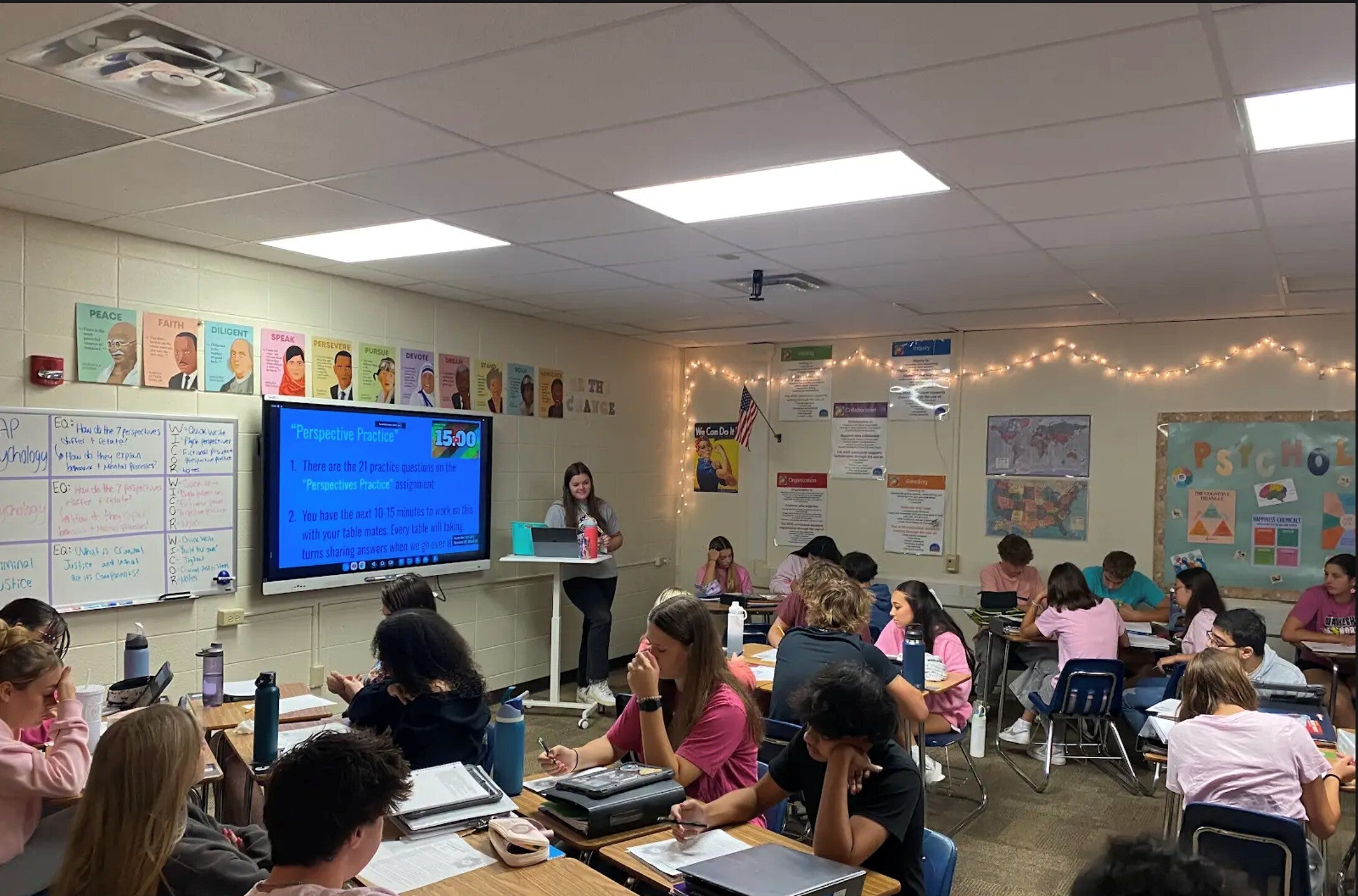

“I think really putting the supports around thinking about what kids already know, creating strong classroom communities, creating classrooms where making mistakes and supporting each other is cultivated — that is what’s going to support more accelerated learning,” she said.

McKinney de Royston and leaders like Wirtz-Olsen of WEAC are calling for more public school funding. School administrators are also focusing on attracting and retaining high-quality teachers and reducing class sizes for those who need extra support.

For all the stress some community members are feeling about children falling behind in their learning, Tesch of the Superior school district said many students are eager to learn in-person and reconnect with friends.

“The ability to interact in a safe environment with their peers and adults, I think, has been a huge missing link,” Tesch said. “That’s why you feel such excitement in the air.”

“Reading and math is critical, and we are focused more than ever on making sure that we’re supporting kids in closing those gaps,” Tesch continued. “But that social piece, it’s pretty irreplaceable.”

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction plans to release data from its Wisconsin State Assessment System at the end of September. Statewide results from the NEAP are expected in October.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.