Wisconsin reading achievement scores are returning back to 2019 levels, but students are still struggling to make up for pandemic learning losses in math, according to a new report.

Researchers at Stanford and Harvard found U.S. students achieved historic gains in math and reading during the 2022-23 school year, the first full year of recovery from the pandemic.

But despite those improvements, students still made up only one-third of the pandemic loss in math and one-quarter of the loss in reading.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Students overall haven’t returned to pre-pandemic levels of achievement,” said study co-author Sean Reardon, faculty director of the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University. “But clear progress is being made.”

School districts are worried the learning achievements made could be lost when federal pandemic funds run out this fall.

Even if they maintain last year’s pace, students will not be caught up by the time federal relief expires in September, the report found.

Poorer students fell further behind, so recovery is taking longer

Between 2019 and 2022, achievement in Wisconsin fell by 37 percent of a grade equivalent in math and 28 percent in reading, according to the report.

Between 2022 and 2023, math achievement across the state increased by 22 percent, but most districts remain far below 2019 levels.

Disparities across Wisconsin persist:

- Milwaukee Public Schools and Racine Unified and West Allis-West Milwaukee School District all lost a full grade equivalent or more in math between 2019 and 2022.

- Howard-Suamico, Elmbrook and Appleton school districts are already scoring above their 2019 levels.

- Green Bay, West Allis-West Milwaukee, and Sheboygan students remain more than half a grade equivalent behind in reading.

The achievement gaps between high- and low-poverty districts in Wisconsin have widened, but that’s the result of larger initial losses in poor districts and the slower recovery of poor students within the average district, Reardon said.

“The recovery has been pretty even, but it’s not undoing the inequality,” Reardon said. “So in other words, kids in most districts are recovering, on average about the same amount. But because the poor districts fell behind so much further, they’re still much further behind.”

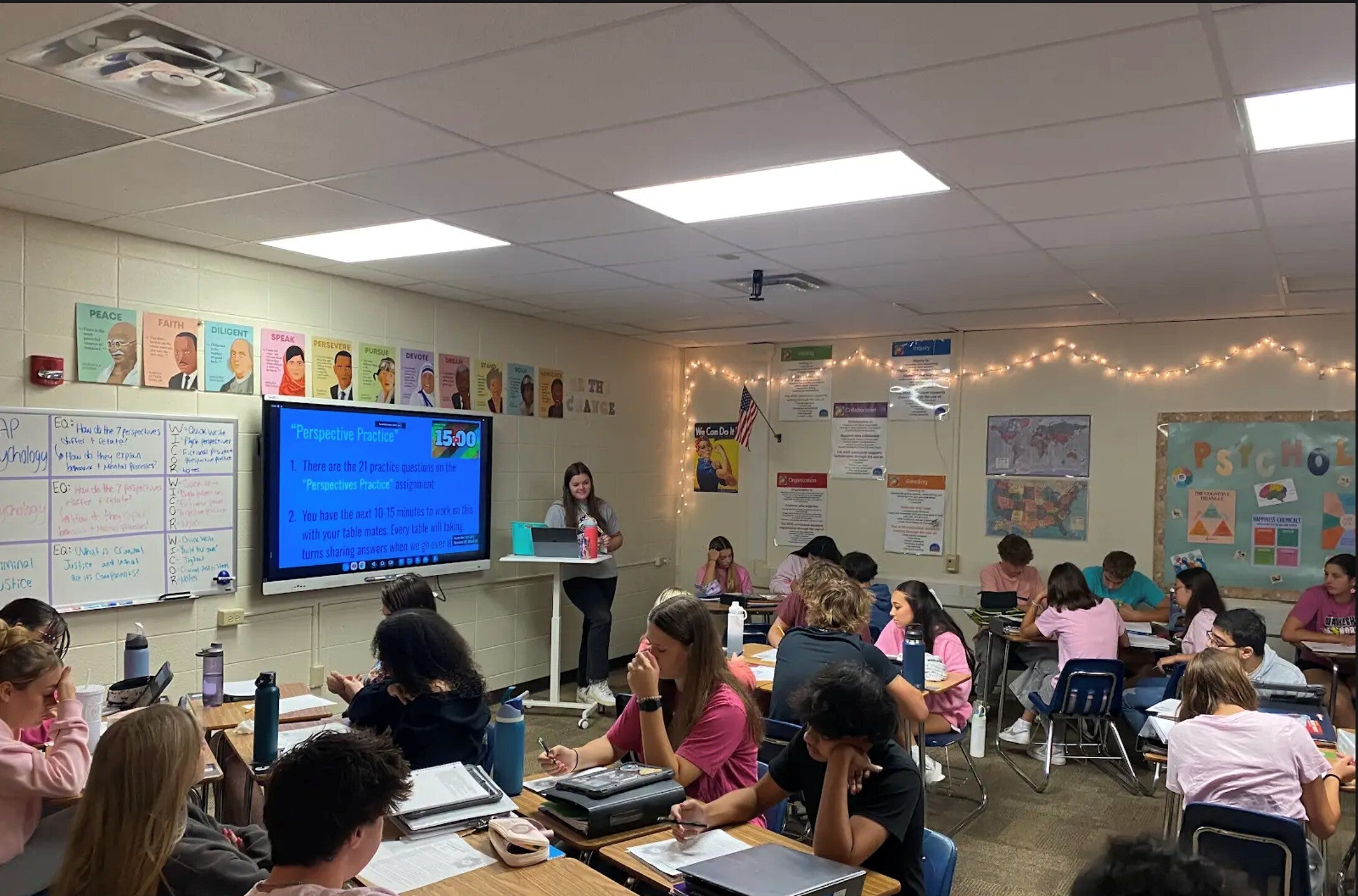

Educators in the school districts have used similar outreach and programing to try to reach students with the help of federal pandemic funds.

A tale of two districts

The Howard-Suamico School District just outside of Green Bay, initiated a task force focused on continuous improvement when the pandemic hit.

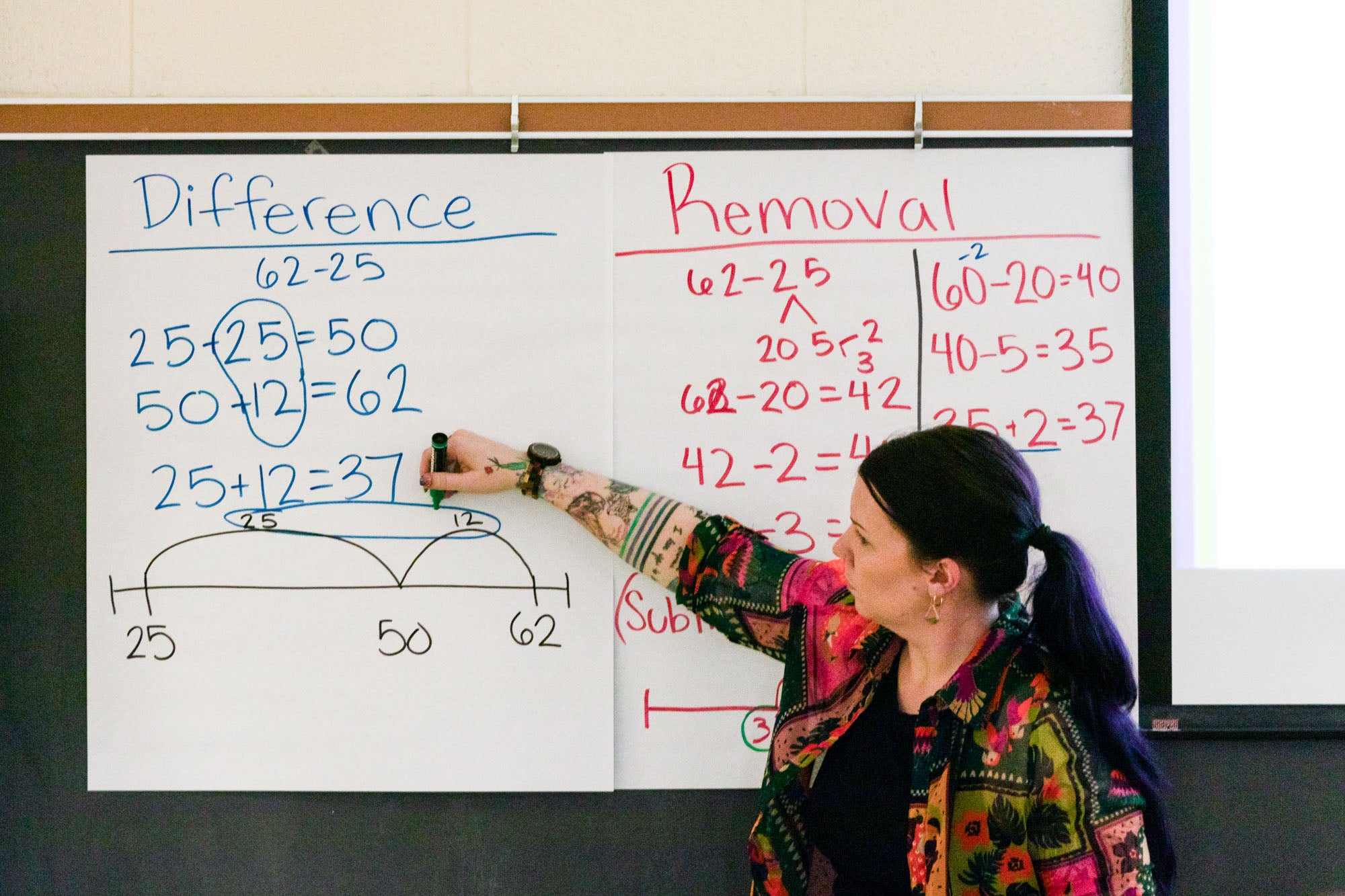

Amanda Waldo, director of teaching and learning for the district, said one of the key strategies has been to put in place study teams for students who are struggling with reading or math.

Teachers use data and create intervention plans for those children to get them back on track, Waldo said.

Last summer, the district launched Learning Leap Academy, a targeted summer school program for students who are in need of academic support.

“It’s almost like a camp,” Waldo said. “They get the bookmobile, our zoo comes and visits them, but they’re also reading every single day, and they’re practicing math every single day. And we’ve seen a lot of great growth from that program as well.”

The tactics have worked. The district’s change in average reading scores in 2022-23 was 35 percent above the national average compared to pre-pandemic levels. Scores for math were 20 percent above the national average last year.

Howard-Suamico has about 5,700 students. More than 85 percent of them are white and about 19 percent qualify for free or reduced lunch.

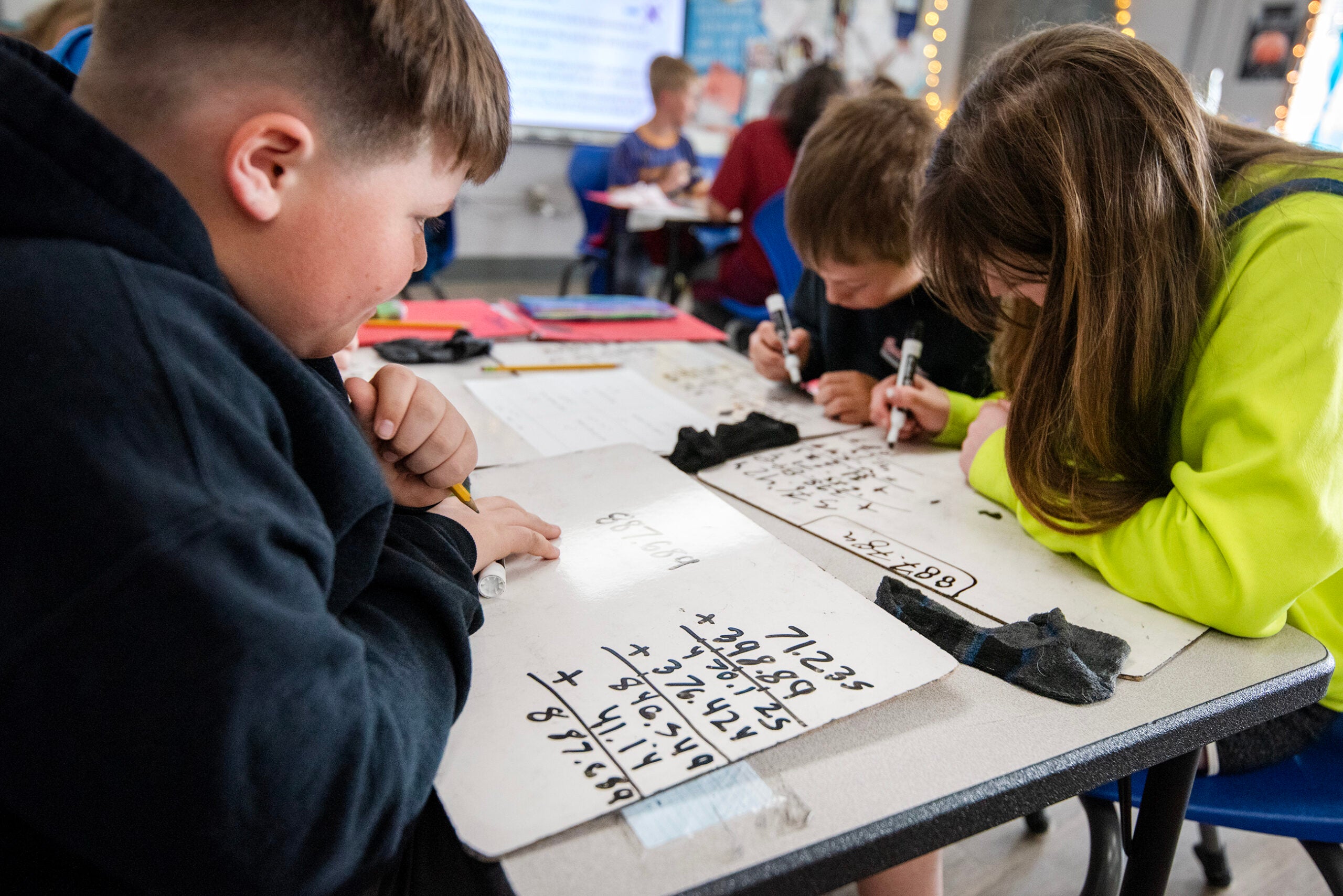

In Racine Unified School District, where there are 16,000 students and 60 percent are economically disadvantaged, educators have also launched targeted summer programs, early literacy programs and a new math curriculum for middle school students.

But the results haven’t been the same.

The district’s change in average reading scores in 2022-23 was 38 percent below the national average compared to pre-pandemic levels. Scores for math were 18 percent below the national average last year.

Janell Decker, acting academic officer for the Racine school district, said attendance and engagement is just starting to get back on track since the pandemic.

And getting parents to participate in academic programs isn’t always easy.

Pandemic money has helped, but will soon be gone

Wisconsin’s public schools received nearly $2.4 billion in three rounds of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief, or ESSER funds, meant to help students make up for learning loss during the pandemic.

Wisconsin received about $1.5 billion dollars in its final round of federal recovery funding. As of February, more than $300 million still needed to be allocated and spent by the end of September, according to conservative Institute for Reforming Government, which reviewed public DPI disclosure documents.

Programs like Howard-Suamico’s Learning Leap Academy and Racine’s literacy work has been made possible by pandemic relief funds.

Both districts worry about what will happen to these programs when the money runs out.

“We are currently looking at our operating budget and seeing what really worked best and trying to keep some of the supports that are showing really good gains,” Decker said. “But I think I speak on behalf of all the districts in saying that it’s impossible to keep all of the things that we see working.”

Reardon said a study is currently underway at Stanford to determine how much of the learning loss recovery is due to ESSER funds. But early estimates show the money has been a significant catalyst.

“The recovery has been much larger than you would predict based on the amount of ESSER funds that were awarded and spent,” Reardon said. “So we don’t know if the ESSER funds caused it, but we do know that the amount of recovery is quite large relative to what even the most optimistic prediction you would have made based on the amount of extra funds available.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.