Free and reduced-price school lunch programs serve tens of thousands of Wisconsin students every school year. However, the implementation of these programs has developed over the course of many decades, and their specific shape and intentions have not always been a matter of political consensus.

Parents, teachers, nonprofit groups and elected officials mostly agree that no student should have to learn while hungry, which is the premise of school lunch programs in the United States. Yet they have often disagreed on the best way to implement these efforts, as well as how different levels of government should play a role in managing them.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Common questions have arisen again and again throughout the history of school lunches.

Who should pay for these programs? Do they perpetuate a cycle where parents don’t feed their children? How can programs end the practice of “lunch shaming“? How could schools work with local farmers to source healthy food? And what about the food included in school lunches? People familiar with this issue might remember when President Ronald Reagan’s administration infamously designated ketchup as a vegetable. More recently, schools are managing the effects of Michelle Obama’s lunch initiative, which promotes healthier meals, sometimes at the cost of kids actually eating them.

The debate surrounding school lunches is multi-faceted. And parents, teachers, pundits and politicians have not been shy to express their many perspectives on the issue. But how did today’s policies get put in place?

The origins of school lunch

Public health historian A.R. Ruis quickly discovered that was a daunting question to answer when he sought to explore the history of school lunches in America. Ruis found that information on school lunches was largely unavailable prior to the passage of the National School Lunch Act — the first federal school meal program — in 1946.

But Ruis continued his research on this topic, and in 2017, published “Eating to Learn, Learning to Eat: The Origins of School Lunch in the United States.” While this book serves as perhaps the most comprehensive timeline of school lunches in the United States, it also presents an original way of thinking about the issue — one that looks beyond its social welfare side or the obligation to serve children who aren’t fed at home — one focusing on a public health frame and the value of educating children on the nutritional benefit of their food.

Ruis, a fellow in the Department of Medical History and Bioethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was interested in the origins of the National School Lunch Program, which he calls the longest-running children’s health program in U.S. history. Through his research on this topic, he discovered why this program operates in what is often a polarizing, controversial policy arena.

“A lot of what the school lunch program was intended to do was to address a much wider range of social health problems — things like educating people about nutrition, health, providing food that would help prevent diseases and disorders, that would strengthen the educational mission by insuring that (students) were well enough fed and nourished,” Ruis said.

School lunches in America have transformed from local, community-based efforts into a nationwide mandate backed by federal law, with widespread implications that continue to evolve. In the 19th century, early reformers argued for school lunch programs based on economic incentives for farmers who grew the food served in schools. They stressed that feeding children would prevent both physical and moral problems; therefore, healthy kids would be more equipped to contribute to the economy. In the last decade of the 1800s, community organizations began providing urban schools with milk, snacks or meals.

Early proponents of school lunch also stressed the importance of not only providing children with food, but also with a food-based education on topic areas like nutrition, health, and food security.

The first U.S. school lunch programs stemmed from “industrialization, urbanization, growing opposition to child labor, increased state involvement in social welfare and public health and, perhaps most important, passage of compulsory education laws,” wrote A.R. Ruis in his book.

Massachusetts was the first state to pass a compulsory education law in 1852. But by 1918, the rest of the nation had passed similar legislation requiring children to attend school. These laws were the first step in transforming schools into uniform civic and social institutions. AS schooling became universal, questions surrounding how to provide children with meals during the day quickly arose.

Challenges in rural schools

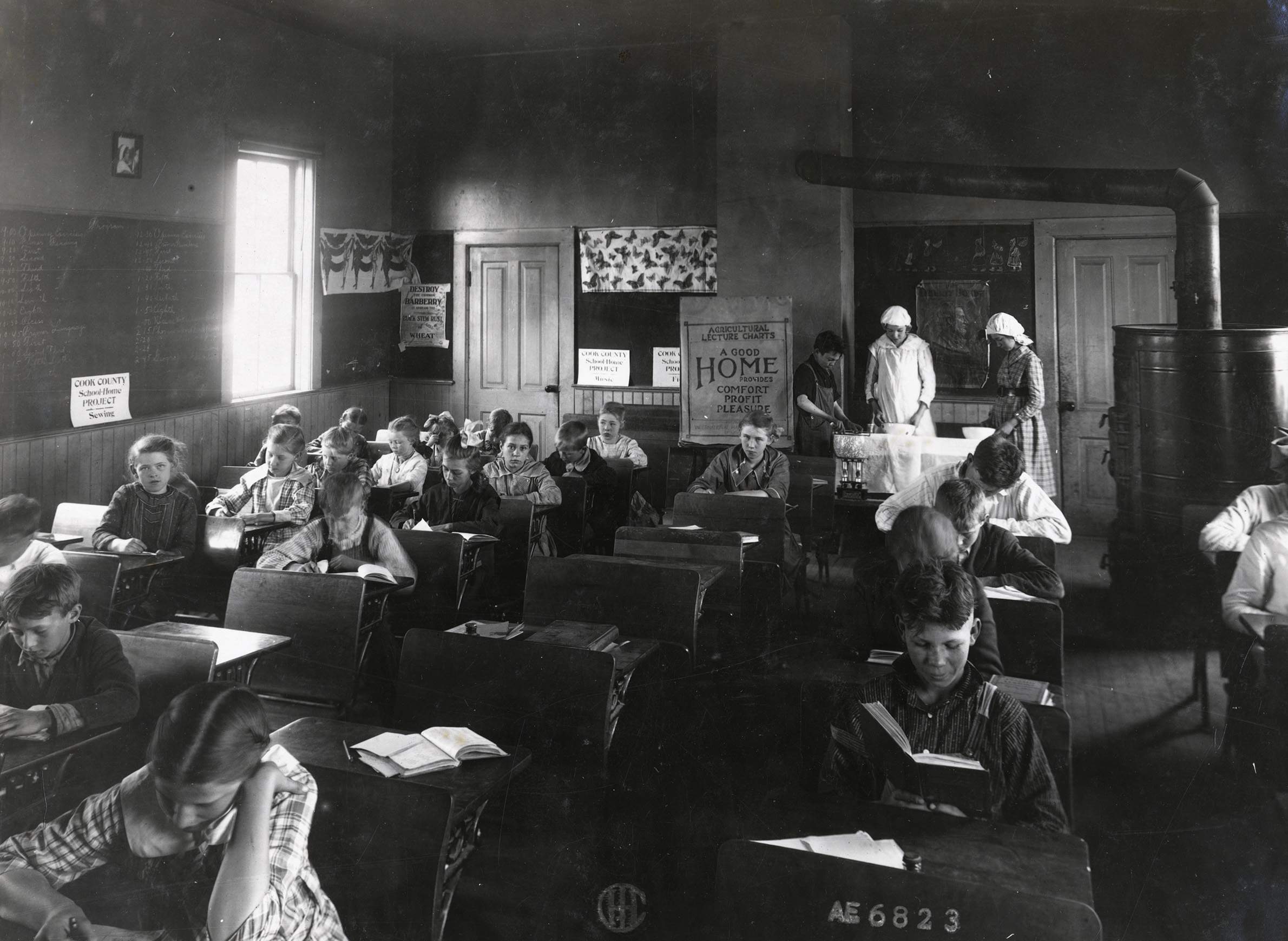

Throughout the history of school lunches, rural schools dealt with their own unique challenges. In Wisconsin, these issues were largely addressed through its aggressive development of programs through UW Cooperative Extension. Challenges rural schools have faced include difficulties hiring a professional staff to serve and cook the lunches, or the economic inability to provide sufficient resources (like cooking equipment, a kitchen, or the food itself), as they had a much smaller tax base than schools in urban areas.

One of the pioneers in establishing rural lunch programs in Wisconsin was Gladys Stillman, a food and nutrition specialist in the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s College of Agriculture’s Extension Service from 1919 to 1953. Stillman worked tirelessly to establish hot lunch programs in rural Wisconsin schools, giving lectures and demonstrations on how to start them. Largely due to her successful and persuasive campaign, the number of rural lunch programs in the state increased dramatically. Before she began her work in 1919, just 215 of the roughly 6,500 rural Wisconsin schools served hot lunches. By the 1920–21 school year, there were 3,148 that did so.

A technique established in Wisconsin to provide rural school students with hot lunches was the “pint jar method,” or the “Wisconsin method.” Through this approach, rural school children would bring a pint jar of food to school to be reheated by their teachers in water over the stove in the schoolhouse. The idea was quickly utilized by other rural schools across the country.

Established by a public health nurse for the Wisconsin State Board of Health in 1920, the pint jar method was especially effective because it required little labor, minimal equipment and little to no investment. It also required no food preparation to take place at the school and it was effective for schools without running water.

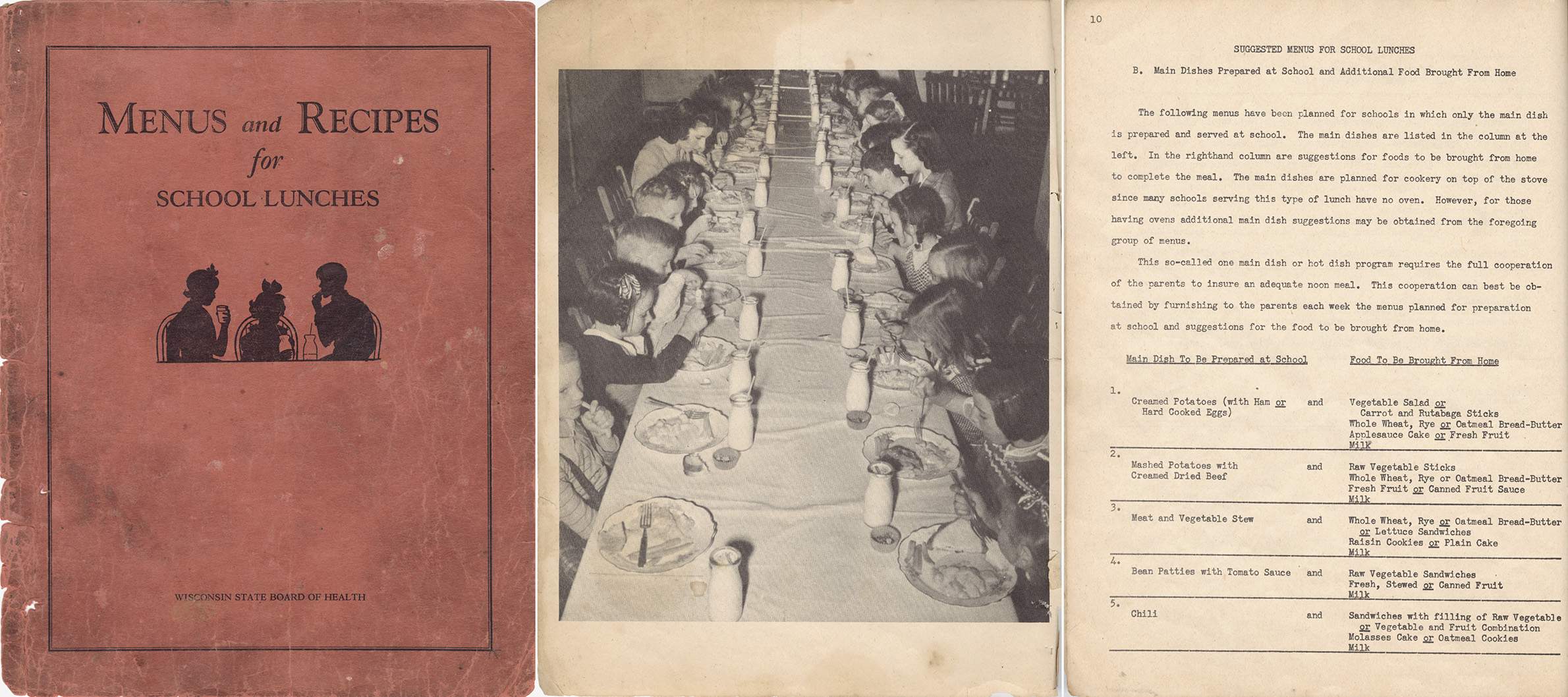

“Not only do the kids want warm food, but the science at the time thought that warm meals were better for you — that they aided in digestion and aided in absorption of nutrients,” wrote A.R. Ruis.

School lunch advocates overwhelmingly backed the idea of warm meals, especially in rural areas where children attended school during the coldest months of the year and when they had the least amount of chores at home. Pennsylvania’s Department of Public Instruction claimed that warm food “saves the body heat and energy, gives a feeling of comfort and warmth, and assists digestion in a general way.”

The idea of a nutritional value inherent to warm food, which has permeated school lunch programs for decades, was established by the pint jar method. Ruis even noted that rural schools coined the term “hot lunch” through this method.

During the 1930s, however, rural schools became increasingly consolidated, therefore shifting their lunches to look more like those in urban areas, with more variety of foods and centralized preparation. When the Great Depression struck the U.S. around the same time, rural school lunch programs were hit the hardest.

In Wisconsin, for example, nearly half of the rural and state graded schools served food in 1924, yet only a third did so by 1933. As the did during the early stages of rural school lunch development, they were forced to develop creative ways to continue their meal programs through low or non-existent funds and whatever food was available.

Federal government involvement

As the Great Depression deepened, the federal government expanded its role in school lunches — therefore opening the debate in the arena of national politics. In Wisconsin, wrote A.R. Ruis, lunch programs expanded considerably.

“A combination of state legislation, improved access to basic public health services, technical ingenuity, and aggressive promotion and education made possible a tenfold increase in the rural schools with warm lunch services,” he wrote.

During and following the Great Depression, reformers sought to create permanent federal support for the issue, which eventually resulted in the passage of the National School Lunch Act in 1946. In the seven decades since, individual states and the federal government have been balancing the competing demands of school lunch programs.

Ruis noted Milwaukee’s uniqueness in the development of school lunch programs in Eating to Learn, Learning to Eat. As the only U.S. city ever to have a socialist government, it was progressive in providing free lunches to many students. The city was the first to propose a bill that would permit school boards to provide school lunches to poor students at any price.

In 1917, the Wisconsin Legislature passed an amended version of a law that authorized school boards to supply lunches, but it stipulated that poor children would first receive the discounted or free lunches. Wisconsin soon thereafter became just one of two states, along with Vermont, that allowed free meals for students.

Another program in place in Milwaukee in the early 20th century was run by the Woman’s School Alliance, which organized volunteers to prepare food in their homes to be distributed to needy schoolchildren throughout the city. It was — and still is — not uncommon for private, community-based organizations to experiment with new school lunch programs with the hope of them eventually serving as the basis for government policy if they are successful.

Return to rural roots

Public school students in Wisconsin’s rural areas often rely on free or reduced lunch at rates higher than the state as a whole, according to the state Department of Public Instruction. In a seven-county region in western Wisconsin along the Mississippi River — Pepin, Buffalo, Trempealeau, La Crosse, Vernon, Crawford and Grant — numbers released in October 2017 indicate that 39.8 percent of students qualified for free or reduced lunches compared to 43.8 percent statewide. However, students in this portion of western Wisconsin utilize free or reduced lunches on a daily basis at a higher rate – 71.1 percent – compared to 66.4 percent statewide.

As demand for these services continues, school districts, businesses and nonprofits are are continuing to experiment with new approaches to feeding students during the day.

One relatively recent development in this arena is the expansion of farm-to-school programs and school gardens, both of which attempt to make menus healthier and more educational by teaching students about biology and nutrition. In some ways, they’re similar to early lunch programs in which farmers would provide rural schools with some of their excess crops.

Farm-to-school programs and community gardens have “significantly expanded” over the past two decades,” Ruis said. The growth of these approaches bolsters his analysis of the overall issue — that school lunches are not only be meal programs, but also serve as opportunities for educational and nutritional growth.

From Mason Jars To Lunch Trays In Wisconsin’s Rural Schools was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.