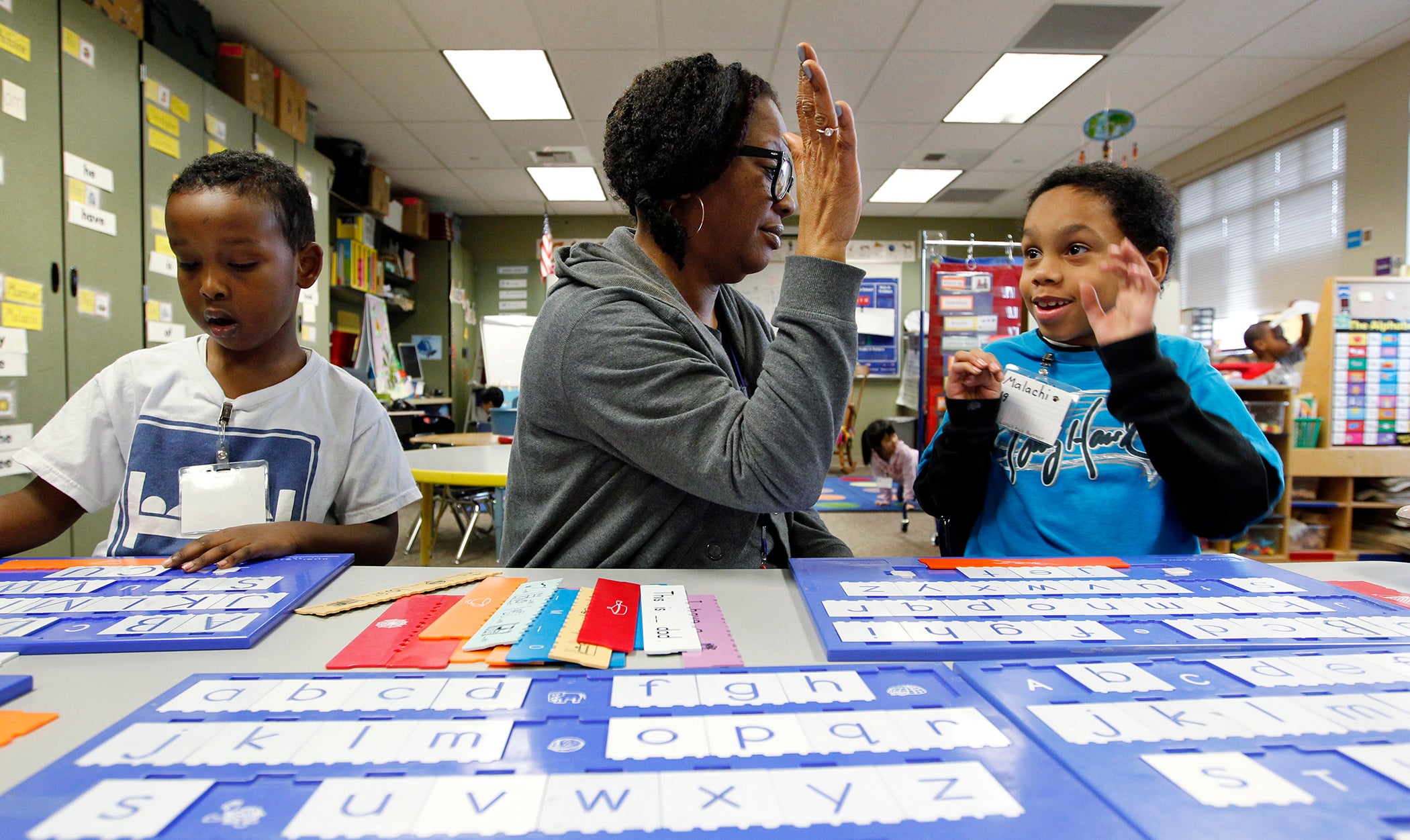

For the second year in a row, the majority of uses of “last resort” measures to control student behavior were used on students with disabilities and elementary school students, according to data released by the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction on May 18.

State law defines restraint as a restriction that immobilizes or reduces the ability of students to freely move their torso, arms, legs or head; and seclusion as the involuntary confinement of students apart from other students in a room or area that they are physically prevented from leaving. It’s meant to be used as a last resort, and to manage a crisis rather than as a disciplinary measure, according to DPI. Students on individualized education plans, used to lay out a school strategy for students with disabilities, made up 85 percent of seclusion incidents and 84 percent of restraints.

“I think it is important to understand that when we talk about students being restrained, students being secluded, it is overwhelmingly little kids with disabilities,” said Joanne Juhnke, advocacy specialist in special education with Disability Rights Wisconsin.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

This is only the second year DPI has collected data on the use of seclusion and restraint in schools, after a state law was signed in March 2020. DPI warned that it’s difficult to draw conclusions from this year’s data, or to compare schools, because it covers the 2020-21 school year, when some schools were fully in-person but others were virtual for part or all of the school year. Last year’s data was similarly an incomplete picture, since schools went fully remote in mid-March of the 2019-20 school year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Juhnke and other people who work in behavioral health and disability rights say that there may be some occasions when restraint, as a last resort, is necessary — Juhnke gave the example of stopping a student from running out into a busy street. However, they tend to agree that there’s not a good reason to seclude students.

“The legal language is kind of dry, but when you think about it in terms of restraint involved physically overpowering a child. Seclusion involves shutting a child alone in a room they can’t escape, no matter how desperately they try,” Juhnke said. “We do these things in the name of safety, but from the perspective of the students, it feels fundamentally unsafe.”

School staff tend to use seclusion and restraint when they are afraid or feel like they’re in danger, said Kim Sanders, one of the chief operating officers at Grafton Integrated Health Network in Virginia. Their behavioral health division made a concentrated effort to stop using restraint or seclusion on patients several years ago, and since then has helped train schools and people who work with children on how to manage unruly or potentially dangerous behavior in safer and less traumatic ways.

“If you have been hit, kicked, bit, hair pulled, it hurts, it physically hurts, and asking people to not let that bother you is not an option, because honestly, you want to feel safe,” she said. “If I can feel safe and my brain is not chaotic, then I can be compassionate, kind, nurturing, and I’m in a good headspace to help you calm and work through whatever’s upsetting you.”

Her organization has taught staff to carefully, gently and defensively block children coming at them aggressively, for example, and then back up and give them space while the staff member buys time to work out a solution that doesn’t involve restraint, and to help understand what’s driving the behavior.

“If a student is restrained or secluded repeatedly, then it’s almost like you’re creating a new pathway in their brain where, you do this, you become aggressive, you’re restrained. What’s lacking in that is the teaching of coping skills, the teaching of different ways to respond, or getting at the heart of why that behavior is happening in the first place,” she said. “If restraint or seclusion worked, then you should only have to do it like once or twice.”

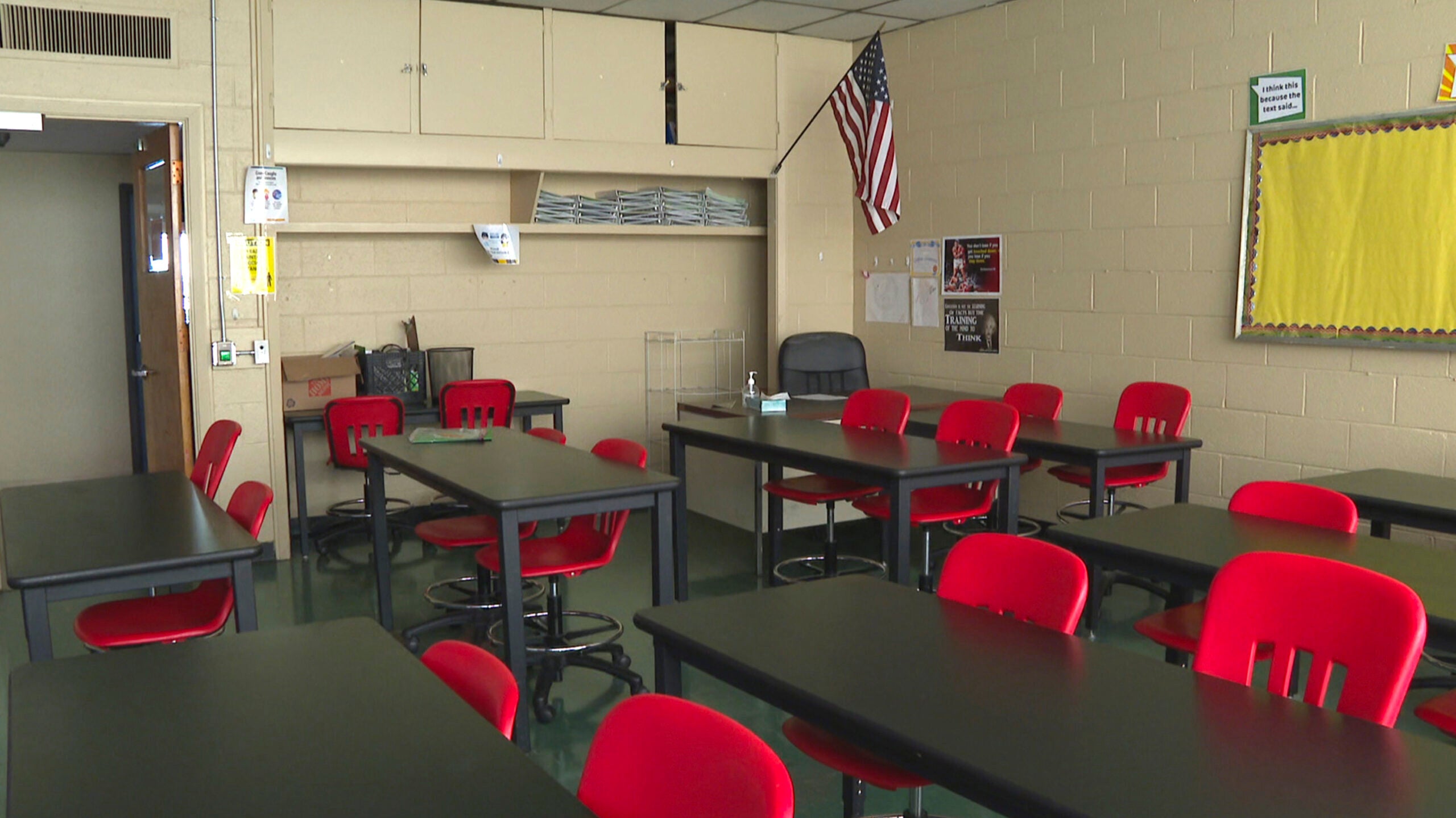

Several of the schools that used restraint and seclusion the most were alternative schools, including Richardson Schools, at 234 seclusions and 468 restraints, and Turning Point, with 233 seclusions and three restraints.

“One would think — one would hope — that schools where students who have struggled in their neighborhood school, that are designed for students having these struggles, would be able to bring something better to the table,” Juhnke said. “It’s distressing and disheartening to see that that is not the case.”

They’re often used on a small subset of students — only five at Richardson were secluded and 21 were restrained, for example. All of them were students with special needs.

“It’s just kind of heartbreaking to look at some of the numbers and see high numbers of these incidents happening, and it’s only one or two students that it’s happened on,” said Juhnke. “That speaks to a repeated failure to figure this out.”

Of the schools with the highest use of seclusion and restraint, 14 of the top secluding schools were elementary schools, and eight of the top restraining schools were elementary schools.

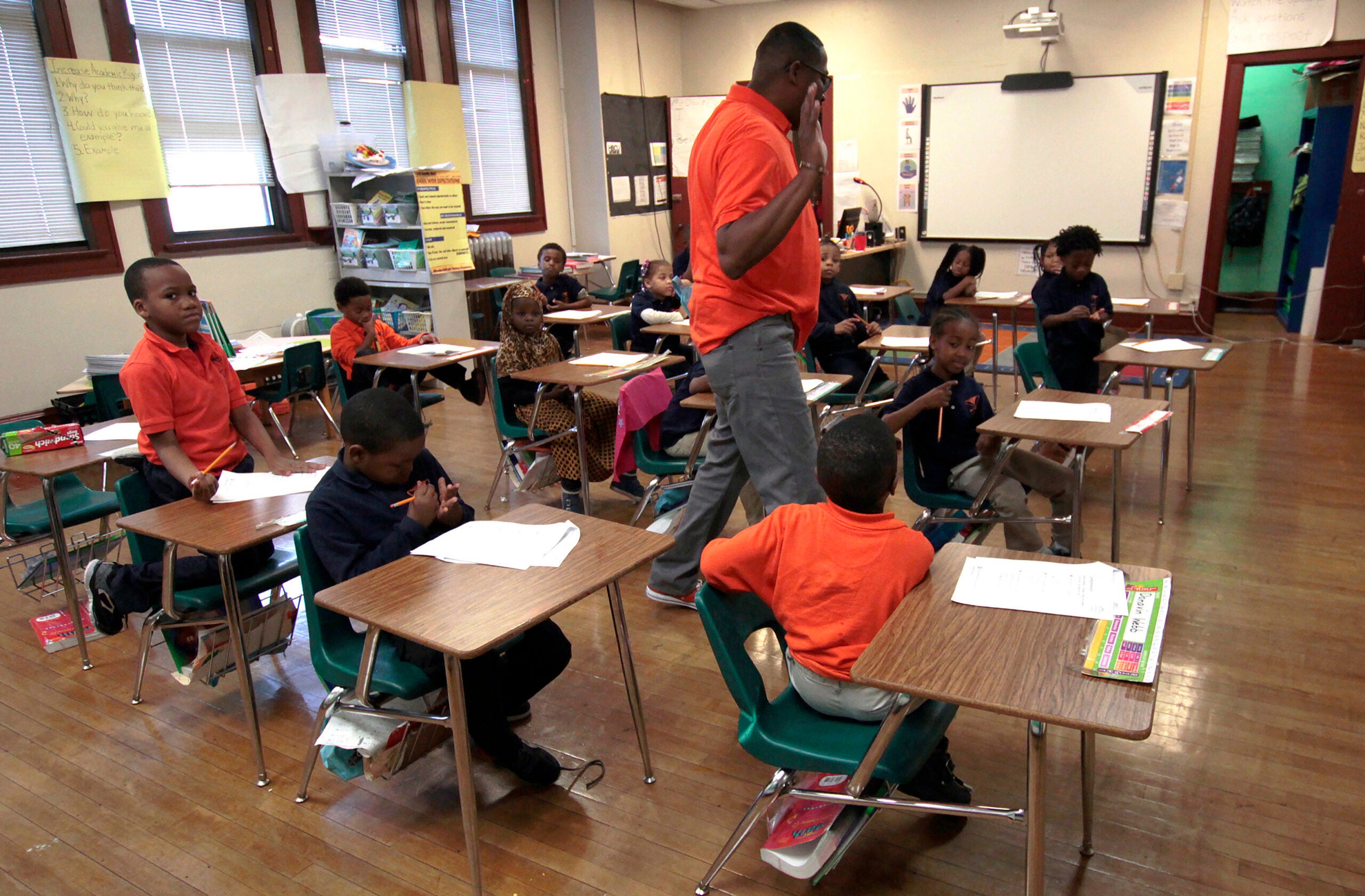

In Milwaukee, home to the state’s largest school district, four students were secluded and 13 were restrained, including those at Milwaukee Public Schools, public charter schools, and voucher students at private schools who also had to report to DPI. That’s a significant decrease from the previous school year, though the public schools did not start returning students to classrooms until February, with most not returning until April.

In Madison, which was similarly conducting school remotely at its district campuses for most of the year, 31 students were secluded and 41 were restrained, with the majority of both being students with special needs. There were also far more overall instances of seclusion and restraint being used in Madison than in Milwaukee.

There are no federal laws outlining seclusion and restraint policies in schools, though the last decade has also seen repeated attempts to pass laws at the national level. In Wisconsin, a coalition has been pushing for changes to the state’s policies on restraint and seclusion for years. Juhnke’s organization, as well as the child advocacy groups Wisconsin FACETS and Wisconsin Family Ties, asked for changes that would get incident reports into families’ hands, prompt debriefing meetings and reassessments of students’ individualized education plans after restraint or seclusion was used, and require schools to submit their data to DPI — all of which made it into the changes signed into law in March 2020.

The data reported to DPI is limited — it’s only broken out by disability status; not by race, gender, age or any other demographic distinction. It also doesn’t show how many restraints and seclusions were done by school staff versus how many were by law enforcement. Research has repeatedly shown that Black students are disproportionately disciplined in schools, and Hispanic students tend to face higher rates of discipline as well.

Since schools returned to in-person learning, there have been reports of more disciplinary issues and incidents of students acting out — a fairly typical response to trauma, potentially exacerbated by students also having to readjust to the structure of a school day. Juhnke said she’s worried that could mean that the numbers of restraints and seclusions could rise in next year’s data release, which will cover the current school year.

“I do think that it’s a concern, I think that we have been hearing about a lot of overwhelm for various reasons, a lot of which are pandemic related,” she said.

The feeling of being overwhelmed extends to teachers and other staff as well, especially with a shortage of substitute teachers.

“We all know that when we’re exhausted, or because we’re feeling stresses of the current economy playing out in real life, that people’s patience and tolerance are maybe not where they were three years ago,” said Sanders. “You put those two together, and we are seeing school districts that are struggling.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.