Children are the future.

They are also curious, wondering what the future of our planet will look like when they grow old enough to drive, see R-rated movies, work (yuck), vote, rent a car or ultimately have kids of their own.

A class of fourth graders from Green Bay public schools recently submitted questions about renewable energy and the environment to WPR’s “The Morning Show.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Greg Nemet, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s La Follette School of Public Affairs, joined the show to answer those questions.

The following answers were edited for brevity and clarity. The kids, however, were perfect.

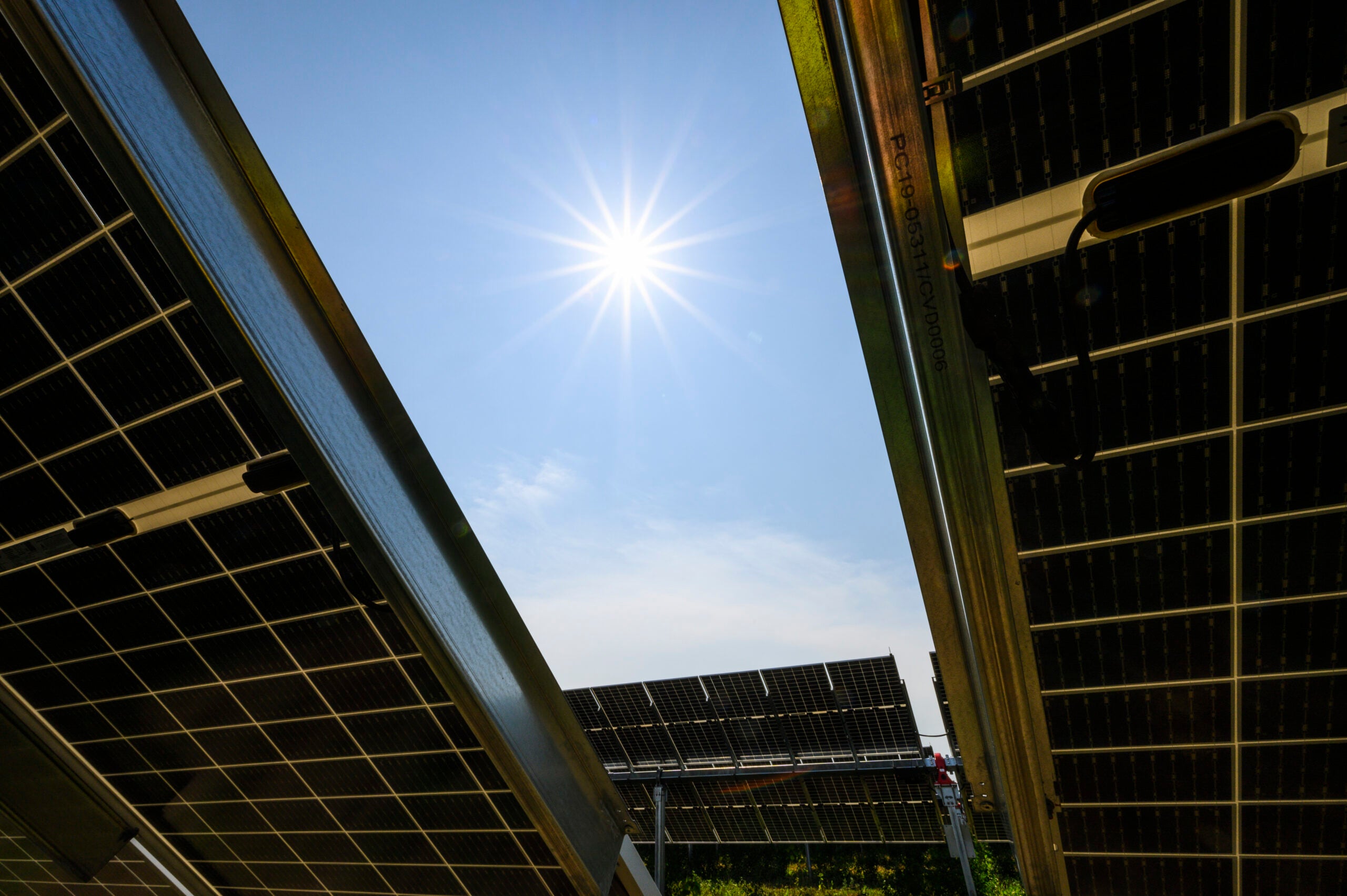

Hailee: My team and I were wondering: How are solar panels made, and is it actually clean to make them? Or do we use fossil fuels?

Greg Nemet: Great question. There’s a lot of benefits of solar. There’s no fuel. There’s nothing to burn. There are no moving parts. One of the other benefits is it’s made from the second-most abundant element in the Earth’s crust, which is silicon.

[[{“fid”:”1631026″,”view_mode”:”embed_portrait”,”fields”:{“alt”:”Greg Nemet”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EProfessor%20Greg%20Nemet.%20%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20UW-Madison%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Greg Nemet”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Greg Nemet”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“alt”:”Greg Nemet”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EProfessor%20Greg%20Nemet.%20%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20UW-Madison%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Greg Nemet”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Greg Nemet”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Greg Nemet”,”title”:”Greg Nemet”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]So, you take this form that sometimes is like a rock — like quartz or sand — and you heat it up in a furnace. You draw out a crystal of crystallized purified silicon, slice it up into wafers, put some other elements on it to make it a semiconductor, put some wires on top of it, some glass and coatings so it doesn’t reflect the sun, a metal frame. And that’s it.

RELATED: Increasing investment in natural gas is a mistake, Sierra Club Wisconsin official warns

And really, the only thing in there that we have to be careful about is where the energy comes from heating up that silicon and melting it. That could be done with coal as it is in some places, or it could be done with renewables or solar itself. So, there is this idea that we could get to this kind of breeding system where we use solar to make more solar, and then it really is clean. There are some emissions in the way that we heat up solar today, but it’s more than offset by the clean energy that solar produces. … It’s a situation that’s improving as the system gets cleaner.

Bristal: My team and I were wondering: How much energy do wind power plants make each year?

GN: This is exactly the type of question that my students are answering in the problem sets in the exam they’ll take later on this week … the math you learn in middle school is really all we use in that class. It’s all you need to answer really important questions like this one.

There are different sizes of wind turbines. They’ve been getting bigger over time. But for the ones that we see around our state … you get about one wind turbine to power about 1,000 homes. For bigger ones — like now we’re starting to do offshore wind turbines maybe coming to the Great Lakes — then from one turbine, you get about 5,000 homes. And usually when you have a wind turbine, you do them in groups because it’s easier to make them work together. For large wind farms, you might have about 200 turbines, 100-200 yards apart from each other, but together in a farm. So, if you did that with these large offshore wind turbines, one wind farm would power about 1 million homes. That’s about half of the homes in our state. You can actually get large amounts of power by aggregating these wind turbines as they get bigger.

What do you do if it’s not sunny and not windy and you’re depending on renewables? That’s been a big question that has come up recently, and we’re starting to get answers to that. You put renewables like solar and wind together because it’s not sunny and windy at the same time … Storage, that’s something that used to be unaffordable that we’re now doing in a big way all over the world and in our states. So, having batteries on the system to store power for a few hours. Then maybe changing when we use energy, so that we use energy for things that we don’t need all the time when it’s plentiful and avoid it when it’s really scarce.

Colten: How much energy does one person use in a day?

GN (who clarified some data points in a follow-up email): That will be a question I’m going to put on my problem set for my class next year. It’s a great question. It’s one of those, it sounds simple but not that easy to answer.

The first thing I’d say is it depends on who you are. So, when we think about energy, it’s not just electricity. It’s transportation — supporting gasoline in a car — and heating, like burning natural gas to keep you warm. If you look at the world, someone uses about 63 kilowatt-hours in a day.

RELATED: Wisconsin’s largest utility company plans to drop coal by 2035

Those are pretty abstract units. Just to put them in perspective, it’d be like taking three space heaters and having them run on full all day. One person’s energy use is equivalent to three space heaters running all day. In the U.S., we’re about four times that. In Africa, it’s about 1 percent of the U.S. average. So, it really depends on who you are and where you are in terms of how much energy you use.

Gillian: How was electricity first discovered?

GN: If you go way back, there’s electricity in nature. People have seen electric eels and some fish; that was observed a long time ago. Lightning is clearly obvious. As science started to make progress in the 1600s and 1700s, there is this understanding of magnetic fields, and then electric fields are related to them. In the 1800s, we really started to understand how electricity is made, but we also start to make it ourselves and start to take full use of it.

That’s a real burst of innovation — probably more than any other period in the last 200 years — where we had electric power, and then lighting coming out of that, and radio and later television. All of that happened in the late 1800s with harnessing electricity. So, a fundamental invention that people observed but took a while until we could really harness. And now, it really is considered something that is critical infrastructure we depend on in our daily lives. It’s not something that’s just for gadgets. It’s something we really depend on.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.