Jennifer Frazer was in a plant pathology class in college and happened to take off the lid of a petri dish filled with soil bacteria. It smelled like dirt, but there wasn’t any — only little patches of bacteria colonies.

“It suddenly struck me — dirt doesn’t smell like dirt, it smells like bacteria,” she said of her epiphany moment.

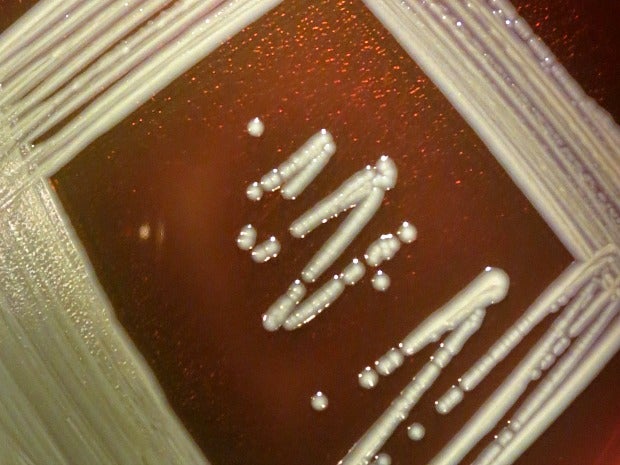

That bacteria she was smelling? Streptomyces, Frazer writes in her recent blog post for Scientific American. Streptomyces are sources of most of the major antibiotics we rely on, such as streptomycin, an antibiotic that gets its name from the bacteria, Frazer said.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

In fact, it’s likely that streptomycin are useful to humans as antibiotics because they’re so used to fighting other bacteria in the dirt for resources.

These bacteria are a bit peculiar in that they act more like fungi. They grow in much the same way, and they produce spores, a lot like the fungi that grows on moldy fruit, Frazer said. That’s important, because those spores are spread by bugs who are much more reliable than water and wind.

Scientists in Sweden made this discovery, published in April in Nature Microbiology, by placing sticky traps and baiting bugs with the bacteria. They found the baited traps, as compared to control traps, attracted springtails — omnivores that are the size of a period.

“They’re super cute and they live in the dirt and …they can eat all kinds of things,” Frazer said.

In the Sweden study, antennae on these little bugs actually responded electrically to the chemical geosmin, which is one of two chemicals made by streptomyces that causes the soil to smell like it does. The humble beets that wear this scent well also makes geosmin.

The springtails spread the spores of the streptomyces in part by eating the streptomyces mycelium — which serves a similar function to roots of a flower. Springtails eat that mycelium, and live spores along with it, which survive the trip through the bug’s body, Frazer said.

Frazer said the realization that the smell of soil actually serves a purpose makes the discovery even more exciting for her.

“I mean, it’s not just dirt perfume,” she said. “It’s like the smell of ripe fruit for a springtail. And that’s kind of cool when you think about it.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.