Just beneath the green, rolling hills of western Wisconsin lies a key ingredient feeding the energy boom across America: sand.

The durable sand that’s perfect for hydraulic fracturing is being mined faster than ever before, causing concern about what the land will look like after the rush ends. Now, researchers in a small western Wisconsin county are looking for the best ways to repair the land before the companies leave.

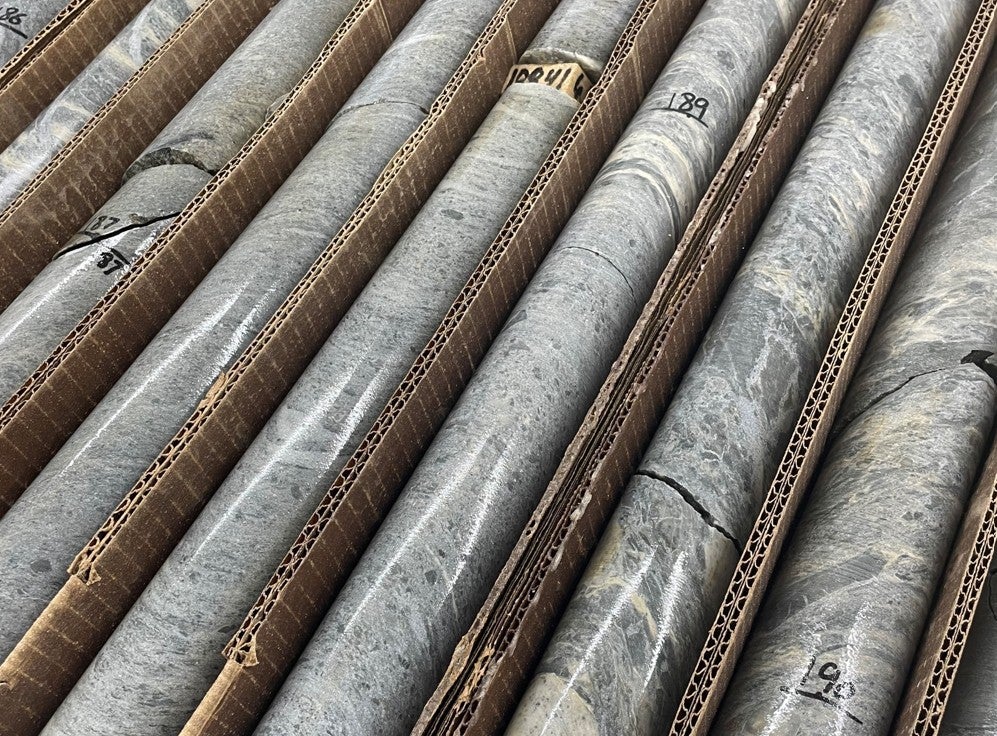

At wells across the country, Wisconsin sand is mixed with water and chemicals and forced into rock formations at intense pressures. The process releases valuable oil and natural gas, in a process commonly known as “fracking.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Wisconsin law requires frac sand companies to show local governments how they’ll fill in their mines in a way that will avoid future soil erosion and runoff at the site – what the industry calls “reclamation.” Exactly how they do that is basically up to companies, leaving unanswered questions about how the soil is impacted by mining and how healthy it may be after a company moves out.

In an effort to answer those questions, a first-of-its-kind study is underway in Chippewa County.

“We’re basically removing the soil, we’re stockpiling it, we’re mining out material that’s below the soil and now we’re putting that soil back on the surface,” said Holly Dolliver, a soil scientist at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls and a lead researcher on the project. “Presumably, there’s going to be some changes that are going to happen to that soil when we scrape it off and stockpile it for a period of time.”

To quantify those changes, Dolliver and a group of graduate students will spend this summer measuring soil before it’s scraped away for mining.

“We’ll be looking at the physical characteristics of the soil, we’ll be looking at the chemical characteristics, and we’ll be looking at the biological characteristics of the soil in that natural or native setting,” said Dolliver. “And, then with that data, we’re going to be able to look at that soil after it’s been reclaimed and actually be able to quantify what those changes are.”

Dolliver and her team will establish test plots where they’ll add varying levels of nutrients like manure and agricultural lime to see which promotes better biological activity and plant growth. But she says one of the most unique parts of the study will be determining whether fine clays and silts – currently considered waste by frac sand companies – can be used to improve water retention in reclaimed soil.

“To our knowledge, no one has ever attempted to look at using the fines in the reclamation process,” said Dolliver. “Like all waste materials that get generated, we’re trying to find a beneficial use for this material.”

While most of the frac sand mines in Wisconsin were built after 2010, Badger Mining Company, based in city of Berlin, has been mining and reclaiming land for more than 30 years. Marty Lehman, an associate with Badger, says reclamation is a learning process and that he’s excited to see what the Chippewa County study will find.

“It’s a great opportunity to help develop new techniques,” said Lehman. “They’ll have ideas that maybe we didn’t have. They’ll try things that maybe we didn’t try. We’ll have experience and hands-on examples of what can be done, or what we tried that didn’t work.”

Dan Masterpole is the director of the Chippewa County Land Conservation and Forest Management Department, which is sponsoring the reclamation study. He says the overall goal is to find best practices that companies across Wisconsin can use to make sure thousands of acres of land slated for mining can become productive again after companies have moved on.

“Up until now we have very limited experiences, collectively, in reclamation,” said Masterpole. “There have been a couple companies that have a pretty good track record, but for many of us reclamation means just getting a site stabilized. But we think that we need to be able to move beyond that.”

The Chippewa County land reclamation study will last five years, with additional soil monitoring expected well into the future.

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a Wisconsin Public Radio series on sustainability in partnership with Quest, a multimedia science journalism and education project of KQED in San Francisco. You can see stories from other Quest partner stations at its website. Funding for QUEST is provided by the National Science Foundation.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.