A reed grass that’s good at dewatering sludge from treatment plants may be doing as much harm as good. A northern Wisconsin tribe has received federal funding to study whether the non-native plant may be spreading in communities along the south shore of Lake Superior.

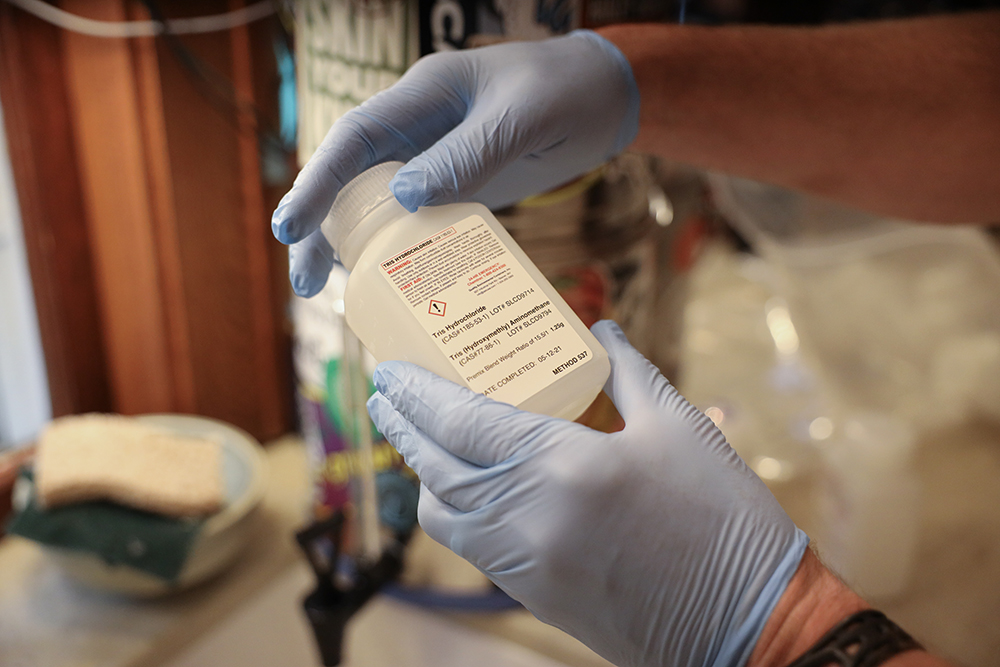

Red Cliff’s Chad Abel, treaty natural resources administrator for the tribe, said they started seeing phragmites pop up around the reservation. All indications were that the grass was spreading from their wastewater treatment plant to isolated locations nearby. The U.S. EPA recently awarded the tribe more than $50,000 to study the genetic makeup of the grass to study if that’s the case for Red Cliff and two other plants in Washburn and Bayfield.

“So confirming this, that it’s either spreading by seed, we’re hoping that the Wisconsin DNR can reconsider their permitting criteria for continuing to allow this plant to be used in these facilities,” said Abel.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Phragmites is an aggressive reed grass that can take over wetlands, but it was once thought to be contained in the reed beds developed for wastewater treatment plants across the state. Wisconsin DNR spokeswoman Jennifer Sereno said 18 facilities are approved to use reed beds for dewatering sludge. But, the discovery of small stands of phragmites around treatment plants has prompted the department to add more requirements under WPDES permits issued to plant operators. In an email, Sereno said, the requirements seek to lessen the spread of the invasive grass.

“Reed bed management requirements work to prevent seed spread by limiting end of season burning of the reed beds and requiring longer term (2 year) storage of removed sludge before land spreading to reduce seed viability,” she said. “Some facilities are also required to conduct surveys at a radius around treatment plants to inventory and treat any satellite populations of phragmites.”

Sereno said the department is also looking at policies to manage the reed beds into the future.

One reason phragmites has been used at treatment plants is that it was a more cost-effective choice for communities. If the study confirms the source of the spread, Abel said removing the reed beds could prove costly – up to $400,000.

“These are three small communities along the Chequamegon Bay. That’s a stretch for any community to come up with those kind of dollars to do what everybody knows is the right thing to do,” said Abel.

Abel said EPA money will also be used to study alternatives that could be used to dewater sludge at treatment plants. A spokeswoman for the EPA said the project is part of a broader effort to protect wetlands along Lake Superior from an invasive species infestation.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.