What changes when we don’t think of humans as the center of everything, or the most special, or the smartest beings on the planet? If you take this idea seriously, there are huge ethical implications. The natural world isn’t just full of resources to be extracted or exploited — animals and plants, even rocks and soil, have their own intrinsic value.

Enrique Salmon has an intimate understanding of this worldview. An anthropologist and professor of American Indian Studies at California State University East Bay, he talks about the Indigenous knowledge that comes out of his own Raramuri culture.

It’s rooted in the land, in the language, and stories that are passed down by the elders.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Salmon teaches a class called “American Indian Science,” in which he asks his students to incorporate their personal experiences into their observations about the world. He says any theory of reality must account for lived experience, which pushes against the scientific paradigm that seeks an objective understanding of reality.

This transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity. The conversation is part of the Kinship series from “To The Best Of Our Knowledge” and the Center for Humans and Nature.

Steve Paulson: You’ve written about the idea of “kincentricity.” What does this word mean to you?

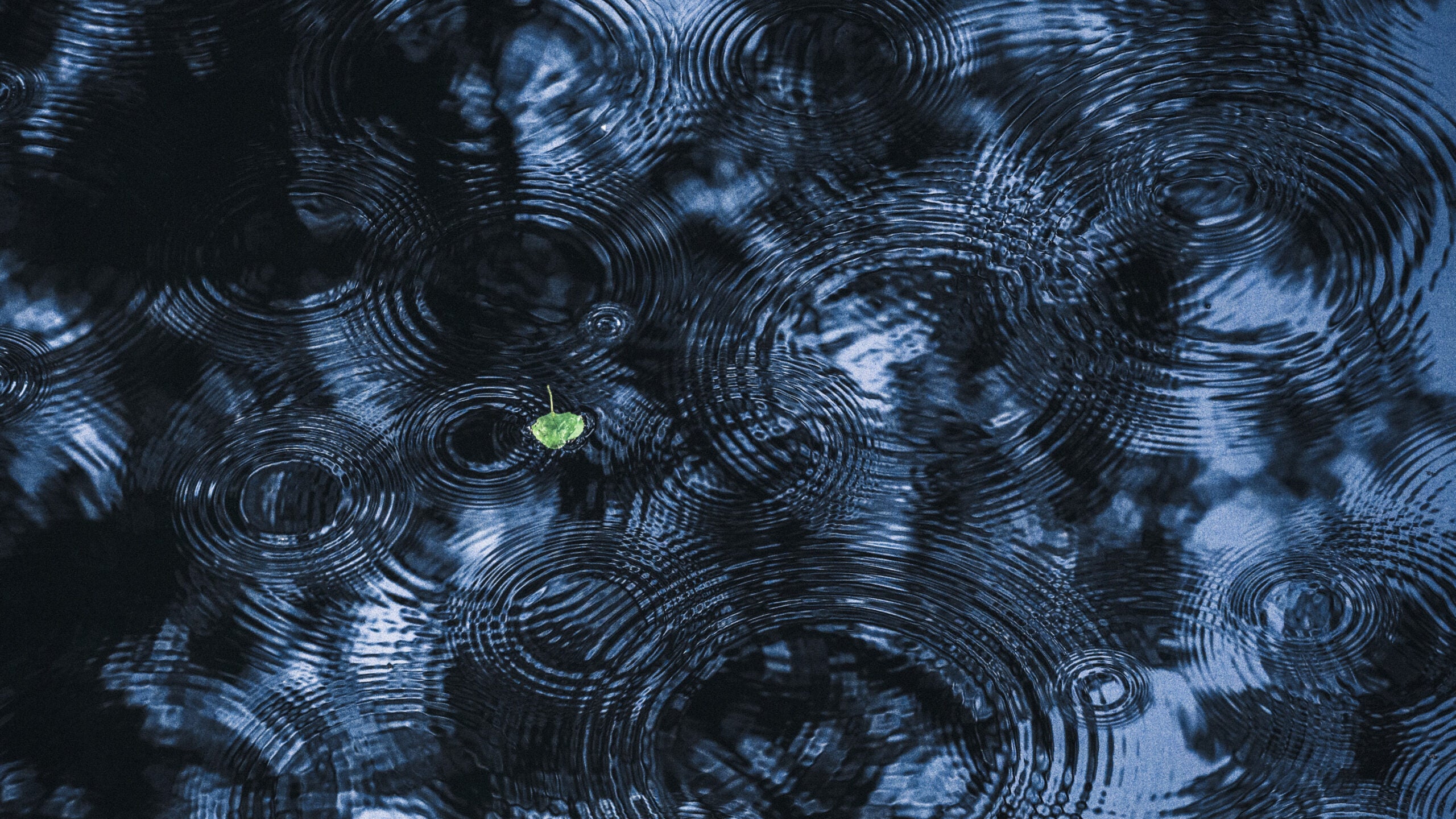

Enrique Salmon: Kincentricity is living with the idea or the worldview that everything around us is a relative and that we share breath with everything. It’s really focused on how the natural world — the plants, animals, rocks, wind, rain, clouds, everything — is a direct relative. In Raramuri, the word “breath” kind of translates into what other people might think of as soul or spirit, or people who study martial arts call Qi or Chi energy, or if you’re into Star Wars, the Force.

SP: This idea that everything around you is a relative is so different from how we normally define who’s family. You are extending this idea of relatedness much further into the non-human world.

ES: Yes, that’s because I was raised in an Indigenous culture, and like a lot of other Indigenous cultures, we owe our emergence into this world to elements from nature. Some cultures feel that certain animals help them get into this world. The Hopi owe a lot of their emergence into this world to Spider Woman. And for my people, we emerged from ears of corn.

So with that worldview, it’s hard not to think of everything around you as a direct relative. It goes into our language as well because the words we use for a lot of plants and animals are the same words we use for our direct human relatives.

SP: What’s an example of this?

ES: There’s a tree that grows at the bottom of the Barrancas del Cobre. It’s a canyon down in Chihuahua, Mexico that’s deeper than the Grand Canyon. It can be snowing up on the rim and you get down to the bottom of the canyon and you’re picking fresh oranges. It’s quite a magical landscape. There’s a tree down there that you would know as a Brazilwood, and we call it “sitakame.” That is the same word we use for our female aunts.

SP: So certain plants are gendered? They might be identified as either male or female?

ES: All the plants have gender, and they also are identified by ethnicity. For example, there’s a cactus that’s related to peyote. There’s a kind of peyote that certain powerful and knowledgeable shamans use in ceremonies. It’s a little more touchy than regular peyote, and it’s a male plant, but it’s also an Apache. For hundreds of years, we were in constant conflict with Apaches coming down from Arizona and New Mexico and raiding, so it kind of makes sense that a plant that is dangerous and you have to really be careful around might be an Apache.

We call corn “sunu,” which is a female, and so it’s also a female Raramuri. There is another plant that was introduced back in the middle 1600s that came from Europe through the Spanish missionaries, and it’s a male, what we call “chavoche,” which is a white person.

SP: How did you learn all this history of your culture?

ES: I grew up in our language, and so when one is immersed in one’s language, you also are immersed in your culture’s view of reality. In every culture around the world, the language is the culture because the way we think is directly related to how we form our thoughts in our languages. And so a lot came from my grandparents on my mother’s side, and then being around people from my culture as well as down in Chihuahua. We spent a lot of time with my mother and my grandmother, learning about plants, and with my grandfather sitting under his fruit trees and listening to stories and helping him in our cornfield.

SP: Would your grandmother or grandfather take you around to identify plants and tell stories about them?

ES: No, it was never that structured. It was always just what you’d call an experiential education.

There’s something I wrote about called “fig tree moments.” My grandfather had this huge fig tree on the edge of his cornfield, and when it got hot, we’d sit under the fig tree in the shade, and he would just whittle on a piece of wood and tell me stuff. Or there were other times with my grandmother, who had this shack built out of slats, and we would sit in there as she’d be grinding her herbs or drying the plants. In those moments, she would talk about the plants and the animals and the insects.

SP: It sounds like the Raramuri culture is intimately connected with the landscape.

ES: I often tell my students that Indigenous knowledge is local. It doesn’t really transfer across ecosystems. Our cultures emerge from specific landscapes. Our languages give voice to the land, and so a traditional Apache out of the Chiricahua Mountains in Arizona just wouldn’t know what to talk about in the Green Mountains of Vermont.

I teach a class called “American Indian Science,” and one of the semester-long assignments that I give my students is to watch sunrises or sunsets. Once a week for the whole semester at the same time of day in the exact same spot, facing the same direction, they either have to watch a sunrise or a sunset, and then they take notes on what they experience for, like, 20 minutes. For about the first three weeks, they’re wondering, “Why are we doing this?”

But then, all of a sudden, you start to read in their journals how they notice patterns. They notice first that the sun actually moves throughout the year, that it’s either further north or further south, depending on what semester we’re doing this in, but then they start paying attention.

“There’s a deer that comes every morning,” or “there are certain insects hanging around in these plants.” And by the end of the semester, they’ve practiced this form of concentrated mindfulness. They’re listening to what the land is telling them.

SP: I’m so interested that you call your class “American Indian Science.” It’s different from most science classes you’d take in college.

ES: Science is just what we call Western science. It’s a way of explaining how the natural world operates, and developing theses and hypotheses results from observation and experimentation.

Well, American Indians have been doing this in North America for thousands of years, and as a result, developing their interactions with the natural world from those observations. It’s just another philosophy of science. In fact, if you look at the age of Newton, they didn’t refer to themselves as “scientists,” they called themselves “natural philosophers.”

SP: One of the conventions of modern science is that you don’t insert yourself into the story of what you’re describing. You’re supposed to get an objective sense of what the nature of reality is. But you’re saying personal experience is part of American Indian science. You can’t remove your personal experience from your understanding of what’s real.

ES: Yeah, it doesn’t make sense for a traditional Native person to remove themselves from that experience because we are that experience, and that experience is us.

One of my favorite examples of this was at the First Mesa of the Hopi Reservation. We were watching a women’s basket dance, and there were these cells of rain coming across the landscape over by the San Francisco Peaks by Flagstaff. And an elder I was hanging out with saw me looking at it, and he goes, “Yeah, look at that rain. That rain is us. We are that rain. That land over there, that butte, that’s us. We are that butte.”

And he did that several times, pointing out different elements of what was around us. This is not unusual among Indigenous people. We are directly related to these things, and so this objective approach to explaining natural phenomena doesn’t make sense to Indigenous people because those things are us as well.