Usually praying mantids are too few in number and too-well camouflaged to be seen in Wisconsin. However, late this summer and fall, a bumper crop of photos of the distinctive insect predator reached PJ Liesch, manager of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Insect Diagnostic Lab.

“This has just been the best year I can ever recall” for praying mantid sightings, Liesch recently told Larry Meiller on WPR’s “The Larry Meiller Show.”

“What’s been really interesting is folks not only finding praying mantids, but saying ‘I have 3, 4, 5, 6 of them in my yard.’ That really stood out to me this year.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The following interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

Larry Meiller: This year you’ve seen and received a lot of reports of praying mantids in Wisconsin. Why do you think that’s the case?

PJ Liesch: We really only have two species of praying mantids that we see. Neither of them are native here, or to North America for that matter, but they seem to be much more common to the south and to the east of Wisconsin. So even if you go a little bit south — Indiana, Kentucky, Virginia, places like that, where they have milder winters — the mantids seem to do better.

But if we have a mild winter in Wisconsin, I tend to see an increase in reports of summer sightings of mantids. It really goes back to the weather pattern we had last winter. We had those very mild El Nino conditions. We didn’t really get a super hard polar vortex compared to other winters.

But usually what happens is, once we get to that first hard frost in the state, that puts an end to mantid activity here.

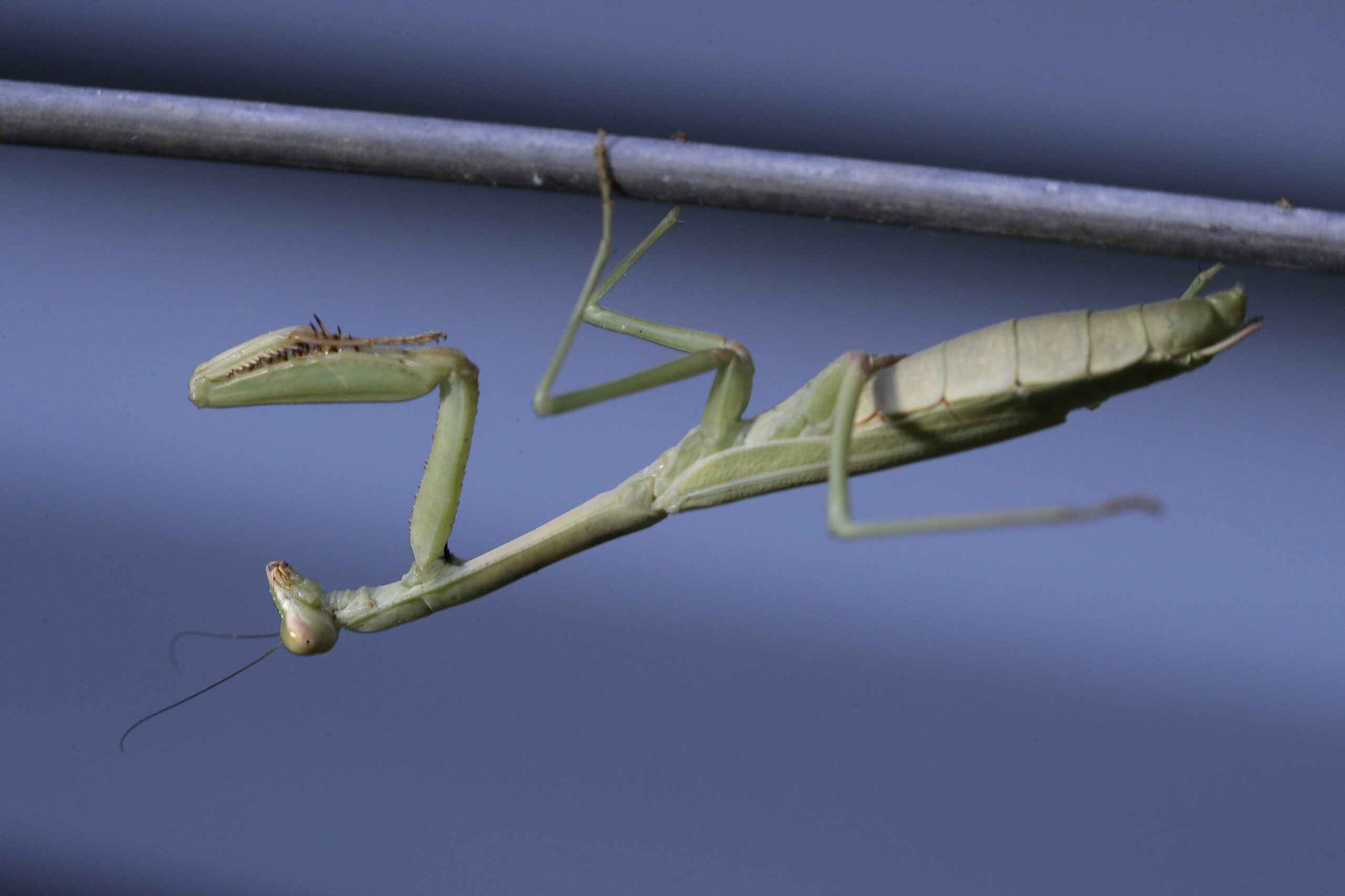

LM: they are very good at camouflage, and so I think that’s one reason they go unnoticed.

PJL: Yes, they are masters of camouflage. It makes sense when you think about their biology and their behavior. They are generalist predators, so they feed on whatever they can catch, usually things that are smaller than them. They rely on blending in, having this cryptic camouflage coloration.

And they move very slowly so they’re not very noticeable. They ambush prey when they get close enough. And they’re very, very efficient at that.

If I were praying mantis, I would basically have spines coming out of my biceps and forearms. So if I were like that and gave something a hug, that would be a lethal hug for prey. So that’s what mantids are doing. We call those raptorial forelegs. They make you think of raptors; birds of prey.

We know mantids do very well in open areas compared to deep in the woods. They really do well around human dwellings urban and suburban areas. And we know they can be strongly attracted to lights.

If they can sit at a light and not have to spend much energy because insects are coming to them, that can be a very good strategy for them. I have gotten a lot of reports where folks say, “I found this one at my front porch light or my back deck light.” That can be a very common phenomenon.

LM: What’s the life cycle of a praying mantis?

PJL: They overwinter as an egg case, called an ootheca. These can be on very exposed locations. It could be a twig or part of a plant, or I’ve even seen pictures of them on gardening stakes. So when we get a polar vortex or really cold temperatures, it does a number on those exposed egg masses.

Sometime in late spring/early summer, depending on the temperatures, the nymphs emerge from the egg cases, and there might be 100 or more of those. And because they’re cannibalistic, they kind of scatter to catch live insects to feed on. They’re molting a number of times as they are growing and developing.

They reach maturity sometime in late summer. That’s why most of reports of mantids come in late August, September into early October.

LM: How beneficial are they?

PJL: There have been some studies, and there’s no clear-cut answer. Keep in mind the two praying mantid species we see — the Chinese mantis and the European mantis — neither of them are native here.

In Wisconsin, I have technically seen one native North American species called the Carolina mantis. But that species does much better in warmer, almost subtropical climates.

So, if you are finding a praying mantis in Wisconsin, it is almost certainly not a native one. And I would say 80 percent to 90 percent are Chinese mantids. And the largest mantid we see in Wisconsin is the Chinese mantis. They can get into the range of about five-ish to close to six inches long.

Folks wonder, because they’re non-native, are they problematic in the ecosystem? We have seen more this year, but they’re still not super abundant. They’re probably just out there feeding on some things, but not really throwing a monkey wrench into the machine.

Some folks ask, “Can I buy praying mantids to put in my garden to help control pests?” If you were to purchase an egg mass, again, the ones that are commercially available tend to be the non-native ones. But if you get 100 or 150 nymphs out of an egg mass, you’re going to have cannibalism. You might get one or two that survive to become adults, and those may leave your yard. So they’re not really a great way to go about biological control.

I’m not aware of any source for native mantids. If you are interested in purchasing some in an egg case, they are extremely labor intensive to raise because 100-plus little juvenile mantids can emerge, and you need to feed every single one of those live prey. I know folks that do this, and it can almost be a full-time job. You have to move them into separate containers, feed them live, wingless fruit flies and increase the prey size as you go.

I had an egg case that I found late last year … but I didn’t get any mantids out of it. The previous year I did. I was waiting, waiting, waiting, then one day all of a sudden — boom — I’ve got like 150 of little ones. I gave away a lot of them as quickly as I could.

I know some folks will purchase mantids as an exotic species in the pet trade. And sometimes they spend $50 or $100 just for one juvenile mantid and raise them up. When you see them as adults, they’re about the coolest looking insect you could ever think of.