Waukesha scored a victory with the historic June 21, 2016 agreement to let the Milwaukee suburb draw 8.2 million gallons per day of drinking water from Lake Michigan. But following a years-long negotiation, both the state of Wisconsin and city of Waukesha had to make some concessions. A couple of these requirements may add to the scrutiny the state’s Department of Natural Resources faces following an audit released June 3 that detailed staffing shortages and lax enforcement at the agency.

Based on the agreement, Waukesha must return as much water to Lake Michigan as it draws. After treatment, the city’s water utility will pump this water via the Root River, which empties into the lake near Racine. But in a June 23, 2016 report on Wisconsin Public Television’s “Here And Now,” Cheryl Nenn of environmental advocacy group Milwaukee Riverkeeper predicted that wastewater flowing back from Waukesha would degrade the Root.

“(Racine residents) are not getting anything from this diversion that’s positive,” Nenn said. “Racine is getting increased pollution into a river that’s already impaired for nutrients and solids and other things.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The Root River faces challenges from previous industrial pollution, as well as from ongoing farm and road runoff, and there are efforts to address these issues and support recreation at its mouth on Lake Michigan. Racine Mayor John Dickert opposed Waukesha’s plan, worrying that phosphorous- or pharmaceutical-laden wastewater could harm boating, fishing, swimming, and the tourism industry in the lakefront community.

John Skalbeck, a geosciences professor at University of Wisconsin-Parkside, told WPT that “from a regional water-management perspective,” the decision makes environmental sense.

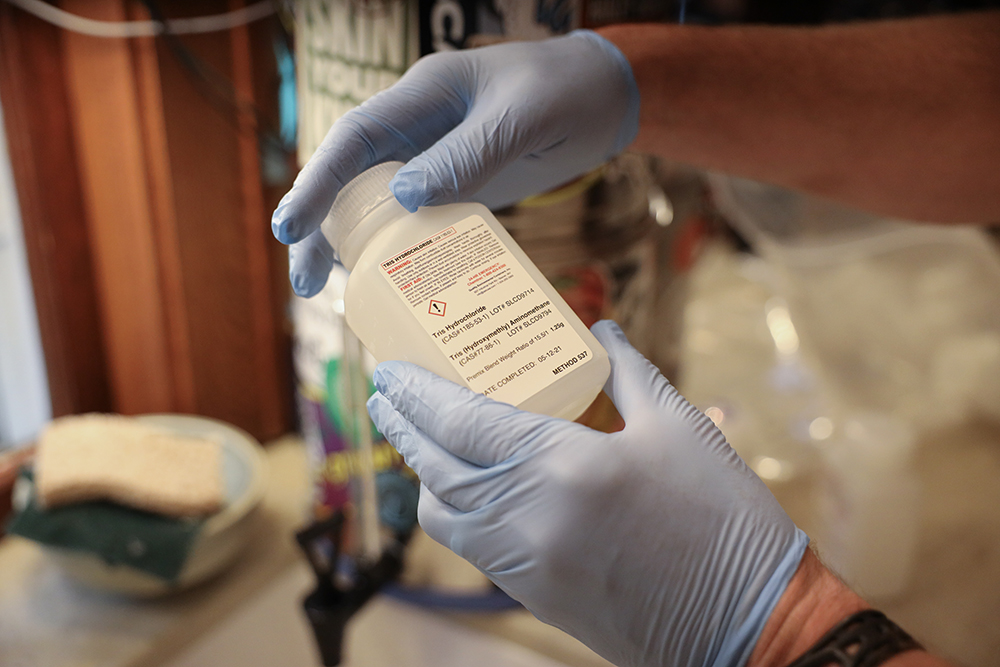

“The current groundwater withdrawal that Waukesha uses for their water supply is not sustainable. It’s not sustainable from a quantity standpoint or a water-quality standpoint,” he said, referring to Waukesha’s long-running struggles with radium in its water supply.

The Waukesha plan required unanimous approval of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Council, made up of the governors of eight states (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New York, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin), who usually send state environmental officials as their representatives for the actual voting and negotiating. Individually and collectively, the other seven states on the council may have just gained some new power to scrutinize Waukesha’s water utility and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Additionally, at least one state has been emphatic about holding Waukesha to the terms of the original Great Lakes Compact governing access for drawing the lakes’ water.

Julie Ekman, Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton’s proxy and conservation assistance and regulations section manager for that state’s Department of Natural Resources, asked the council to add language to the final agreement stating that “any party or the council may initiate actions to compel compliance with the provisions of this compact.”

This isn’t unprecedented — the Great Lakes Compact itself already includes similar language. Adding such an addendum to the Waukesha agreement is partially intended to send a message. In his statement after the diversion was approved, Dayton praised the plan, but added, “strong language was also added to the proposal, affirming the authority of the Compact Council and the individual member states to enforce the conditions of the project as approved, including audit language to ensure the Council and its members have access to the information needed to monitor and enforce compliance.”

Dayton faced vocal opposition to the project from Minnesotans, and held off on voicing his opinion on the diversion until close to the final vote.

Ekman also heard from environmental groups in Minnesota who were concerned about Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel’s decision in May that the Wisconsin DNR has only limited authority to regulate high-capacity wells. “They were concerned that ‘look at this, Wisconsin isn’t going to be able to enforce its water-use laws,’” Ekman said in an interview with WPT after the June 21 vote on Waukesha’s request.

Does this new language means that, say, Minnesota or New York can take Wisconsin to court if they’re not happy with the DNR’s oversight? “That would depend on the issue involved,” said Peter Johnson, deputy director of conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers, the administrative arm of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Council. Member states can work out disputes through the council, but when that avenue is exhausted they’re entitled to go to federal court, he said.

On the other hand, Bill Davis, president of Wisconsin’s Sierra Club chapter, worried that the added language might be toothless. “These provisions also require another state to act and do not allow the citizens of Wisconsin to enforce the provisions of the diversion,” Davis said in a June 21 statement. “We are leery that other states will not take the time or resources to watch over the Wisconsin DNR.”

Another amendment, made at the request of Michigan, opens up Waukesha’s water plants and the Wisconsin DNR’s records to scrutiny from other Great Lakes states. It reads:

“For as long as the City of Waukesha withdraws Basin water pursuant to this approved diversion, the City of Waukesha upon 30 days advance written notice shall allow the Compact Council or any Party to conduct an inspection and audit of the City of Waukesha operations; and the WDNR, upon 30 days advance written notice shall allow the Compact Council or any Party to inspect its records related to enforcement of this diversion and all conditions stated in this Section III.2.”

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder and his proxy before the council, Grant Trigger, also dealt with some home-front opposition. A bipartisan group of Michigan congressional representatives signed a May 26 letter urging rejection of the plan. While the letter didn’t mention environmental enforcement specifically, it did cite a concern for “the health of the Great Lakes and the welfare of all those who rely on them for their livelihood.”

Waukesha is more than two years away from actually tapping into Great Lakes water. It’s hard to say how future disputes over the diversion will play out, Johnson said, in part because this is a first time a community not strictly within the borders of the Great Lakes watershed has gained access to the supply.

“It’s still going through some Wisconsin permitting processes and whatnot, so, there’s nothing to enforce at this point, if you will,” he said.

Editor’s Note: Here And Now anchor Frederica Freyberg contributed to the reporting for this article.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.