Claire Holland’s three years living in Madison mostly coincided with the coronavirus pandemic, which limited how much she could explore.

“Anytime — and this is sincere — when I wanted to go someplace that would make me feel good, I just started driving west,” she said. “And I think I was going into the Driftless Area.”

She found the tree-covered bluffs revitalizing. The ridges and valleys were refreshing. She felt spending time in the area opened her heart and spirit, of that much she was certain. But Holland wanted to know more about the history of the Driftless Area. Where did the name come from? What are its defining features? What are its boundaries?

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

That’s where Wisconsin Public Radio’s WHYsconsin stepped in.

Why is it called ‘Driftless’?

Arriving in the Driftless Area transports you from a relatively flat Wisconsin to a sudden maze of hills. Winding roads roam up bluffs and back down to the valleys below. “Watch for fallen rocks” signs are common along the highways, and flowing creeks and rivers continue to carve their paths.

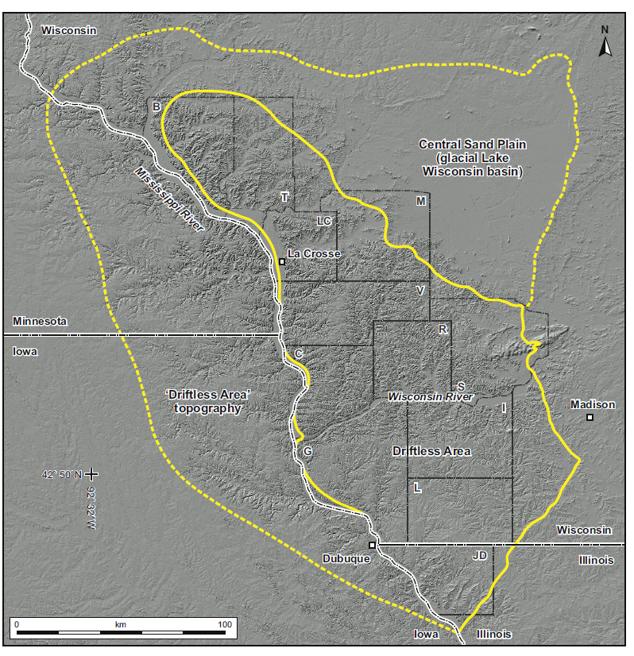

The Driftless Area, which covers roughly 8,500 square miles, features varied geographical traits.

From the Baraboo Range with hills that cover thousands of acres in Sauk and Columbia counties to the Mississippi River that separates Wisconsin and Minnesota. From Wildcat Mountain towering over the Kickapoo River in Vernon County to Perrot State Park, found at the confluence of the Mississippi and Trempealeau rivers.

But the name covering the area comes from the absence of glacial drift, which the group Driftless Wisconsin describes as the deposits of silt, gravel and rock that glaciers would have left behind had they passed through this part of southwestern Wisconsin.

Colin Belby, head of the geography and Earth science department and professor at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, said glaciers appear to have missed the area in southwestern Wisconsin while going through surrounding regions in Wisconsin and the Midwest.

Geologists look for glacial erratics, which Belby said are rocks that stand out because they aren’t native to the location they’re found. He said researchers can study the deposited rocks to figure out where they originated and determine how glaciers brought them many years ago. Those rocks aren’t found in the Driftless Area.

“The absence of glacial drift brings about the name, ‘Driftless Area,’” he said.

Belby said for long periods of time, rivers cut down through the bedrock. When glaciers were in surrounding areas, the meltwater sometimes made its way into the Driftless Area and contributed to the incision that formed the valleys and bluffs, he added.

“It’s really fun to think about,” he said. “Why did all this come together? If you go back far enough, it’s related to oceans that were here 500 million years ago. And (as) you come closer to (the) present, it’s tied to glacial activity in the region and then post-glacial activity of the past 11,000 years.”

What does the Driftless Area look like?

Walking through the Kickapoo Valley Reserve in Vernon County on a Friday afternoon in August, Marcy West said the Driftless Area “feels very untouched.”

“We can see the hills and valleys and get into it, explore it (and) really look at the diversity of plants and the birds,” she said from the southern part of the reserve, a stone’s throw from the Kickapoo River. “Just enjoy the quiet and solitude in some areas like this.”

West was the executive director of the reserve in La Farge for 24 years. She left the job when Gov. Tony Evers in 2020 appointed her to become the southern regional representative for the state’s Natural Resources Board.

While walking through one of the valleys, she said a good rain refilled a pond that’s home to turtles, ducks and herons.

As its geological history differs from regions around it, West said the Driftless Area features a tremendous amount of biodiversity.

Belby explained how the varied topography means interesting vegetation can develop, with some areas offering cooler and shadier environments for growth.

“We have caves here,” Belby said. “We have the Mississippi River. We have small streams. We have medium streams. It’s a really diverse physical landscape that results in a very diverse biological landscape — and also results in a very diverse cultural landscape. All those things are really tied together.”

West said “by far” her favorite part of the Driftless Area is the Kickapoo River. She loves kayaking and seeing the rock outcroppings, the huge pine trees and the hemlock. She said water carved out the “beautiful landscape of hills and valleys that does look very different from the rest of Wisconsin.”

She said she puts a high priority on protecting the water quality in the area, which also can deal with repetitive flooding. Protecting the shorelines and the streambanks, as well as maintaining the area’s biodiversity, remain vital for her.

How far does the Driftless go?

What defines the boundaries of the Driftless Area are “surprisingly controversial,” Belby said with a chuckle. Some popular sources of information show the area extending into southeastern Minnesota and northeastern Iowa.

“That’s actually not really supported by field evidence,” he said.

Those regions in Minnesota and Iowa might look like southwestern Wisconsin. The topographies — a river-carved landscape — are alike. But when looking closely, Belby said you can find glacial material in those other states.

“Visually, it looks like the Driftless Area,” he said. “Technically, it’s known as what we call the ‘Paleozoic Plateau.’ It’s not truly the Driftless Area.”

Technicalities aside, West said she believes southwestern Wisconsin is more beautiful than nearby areas in neighboring states.

After living in Wisconsin, Holland moved back to Florida in May. But she fondly remembers her time in the car, charting a path through southwestern Wisconsin that the last glaciers never did.

“I’ve never enjoyed driving so much,” she said.

This story was inspired by a question shared with WHYsconsin. Submit your question below or at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it.