Wisconsinites are experiencing the power of water politics lately as politicians including Gov. Scott Walker and Racine Mayor John Dickert weigh in on the city of Waukesha’s ongoing bid to source drinking water from Lake Michigan. But even on a normal day, the distribution of drinking water ties Wisconsin’s major population centers together and shapes local economies and political dynamics.

Local governments depend on and sometimes battle with each other to ensure access to drinking water sources and the infrastructure necessary for treatment. The poisoning of Flint, Michigan’s water supply — a direct consequence of that city leadership’s since-reversed decision to stop buying its water from Detroit — starkly underlines the importance of these relationships.

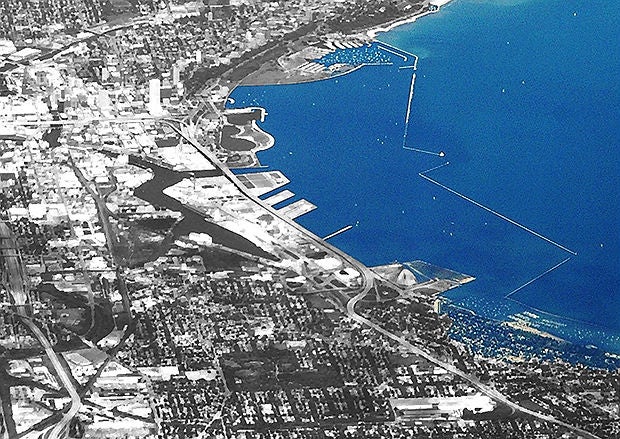

In Wisconsin, drinking water systems are most interconnected in areas where larger cities — Milwaukee, Kenosha, Racine, Green Bay — can source a large volume of Lake Michigan water, draw on relatively large staff and budgetary resources to treat it, and sell it to suburban or rural governments. The customer cities often have smaller budgets and often lack staffs who can dedicate sufficient time to drinking-water issues. Sometimes the larger city includes billing and infrastructure-maintenance services in these deals, serving as the customer’s city’s de facto water utility — this is a “retail” water agreement.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

In other cases, the larger city just sells the water to the customer municipality, which handles everything else — a “wholesale” agreement.

In a couple of instances, small cities band together to run a water utility separate from a nearby major city, namely the Central Brown County Water Authority near Green Bay and the North Shore Water Commission in Milwaukee’s northern suburbs.

It’s not only cities near Lake Michigan that supply water to nearby communities. Madison, which relies entirely on groundwater, ships its water to four smaller utilities in Dane County. To a lesser extent, rural utilities and cities in northern Wisconsin share water resources as well — for instance, Wausau sends some water north to (the soon-to-be-dissolved) Brokaw, a village of about 250 people, while Appleton sells water to nearby Menasha, Grand Chute and Sherwood.

Scott Biernat, director of regulatory affairs and scientific program development for the Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies, said he wouldn’t be surprised if larger cities seek more neighboring customers as they run up against growing water conservation practices and public resistance to water utilities raising their rates. (In Wisconsin, the Public Service Commission regulates rates.)

“Even with rising populations, people are using much less water, so a lot of places have extra capacity in their treatment systems that could be seen as a fairly easy revenue source,” Biernat said.

Keith Haas, Racine’s water manager, joked the city doesn’t gain by selling water to neighboring communities except for “more headaches” for him. But from his point of view, the greatest virtue of communities sharing water resources is the broader effect on local economies. When communities work together to take advantage of economies of scale in drinking-water sourcing and service, that in turn helps to keep taxes and water rates under control, explained Haas. In theory, these cost controls makes each community more attractive for residential customers and new businesses.

“It’s a win-win for the area,” he said.

Sometimes water cooperation helps with less lofty matters, like filling in gaps in infrastructure and service. Racine technically exports water to three other communities and imports water from the town of Somers to its southwest. Even though Racine taps Lake Michigan water, Somers supplies water to three houses and a funeral home in an area of Racine where the larger city’s water mains don’t yet reach.

“It’s not worth me putting in a million-dollar water main for $500 in revenue every year,” Haas said.

Although water sharing among utilities is a fairly mundane reality for someone like Biernat, he explained a smaller community’s decision to connect to or disconnect from a larger utility can be complex. The case of Flint, where residents drank dangerously contaminated water after the city’s state-appointed emergency manager cut ties with Detroit’s water utility, differs from typical water-sharing politics, especially in how fast the decision was made, Biernat said.

“It’s really rare that an established water system is going to change its water source,” he added.

More importantly, Biernat said the Flint tragedy illustrates the need for utilities to incorporate technical skill and scientific knowledge into sourcing decisions — and for regulators and elected officials to understand the implications of potential changes. When Flint switched from Detroit’s water, it lost access to the expertise of the much larger city’s water-utility staff, which Biernat suggested was just as problematic.

“The more you read about Flint, there were particularly egregious failures in the oversight,” Biernat said. “It wasn’t a failure of existing regulation. (And) disadvantaged communities in particular may have problems employing the technical expertise necessary.”

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.