In a place with long winters like Wisconsin, people tend to make use of one of its most visible seasonal resources: ice. Whether it’s a walk across the lake or ice fishing, a local festival or race, ice can make winter more enjoyable and help build community. But if this seasonal cover on Wisconsin’s lakes and waterways disappeared, what would be lost?

Lesley Knoll is a freshwater ecologist and the station biologist at the University of Minnesota’s Itasca Biological Station and Laboratories, as well as an adjunct assistant professor in its Department of Plant and Microbial Biology. Knoll is the lead author of a study that explores how declines in seasonal ice cover can have cultural effects on communities. The social and recreational opportunities provided by winter ice cover are one example of ecosystem services, which are ways people can benefit from the natural environment.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Knoll spoke about this research in a Feb. 26, 2020 interview with Wisconsin Public Radio’s Central Time. The complete audio of this discussion follows, along with an abridged version of the conversation.

Rob Ferrett: Before we get into the cultural side of ice loss and ice melt in Wisconsin, Minnesota and elsewhere in the world, can you talk about what we’re losing in terms of how much ice we see on our lakes from year to year?

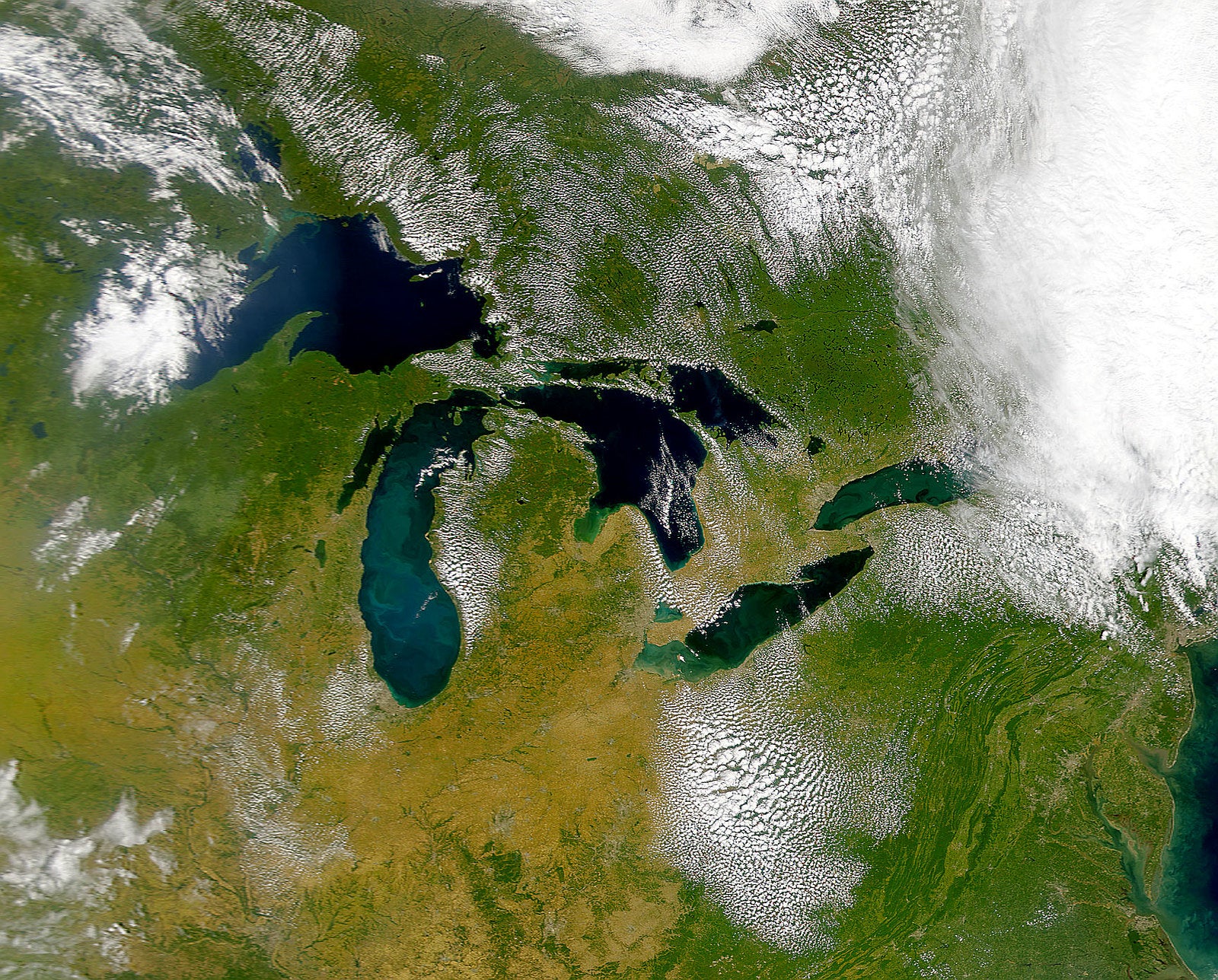

Lesley Knoll: Over about the past century, lakes have been experiencing early ice break up, later ice formation and shorter seasons of ice cover. There’s also been studies that have shown decreases in ice thickness and also increases in the frequency of freeze-thaw events. That’s when ice freezes and then you lose that ice and then it freezes again. We’ve been seeing that in the Northern Hemisphere, including in the Great Lakes region.

A lot of times we would think of that story as a weather and climate change story, maybe an ecology story. You focused on the the human side of things, the cultural ecology — what made you want to tackle that particular issue?

I’ve been working on lakes and more on the ecology side, either as a student or professionally, for over 20 years now, but I find that I’m always kind of drawn to how people are involved, that side of things. I moved to Minnesota — I’m up in northern Minnesota — about four years ago, and my office overlooks Lake Itasca, which is a very popular recreation lake. We’re in a state park and at the headwaters of the Mississippi River.

I’m seeing a lot of recreation occurring in the summer and also in the winter. For example, I’m looking out my window now and I see five ice houses on the lake — trucks out there. So seeing this every day got me really thinking more about how people are using the lake in the winter and what they stand to lose. As we know, ice cover is changing over time.

What kind of cultural events here in the upper Midwest — places like Wisconsin, Minnesota — are feeling the impact of this reduced amount of ice?

Some of what we looked at and some of what’s very popular in the upper Midwest: ice fishing, of course. Ice fishing tournaments is one thing that our study looked at. Ice skating out on natural lakes or hockey [are] pretty common events as well. But even thinking about things like taking pictures of the frozen landscape. People post pictures on Instagram or just take pictures for their enjoyment.

And that’s day-to-day kind of stuff. You also look to understand winter-themed events that rely on that ice that sometimes get canceled?

We’ve got different ice palaces or different festivals that occur on the ice every year. So those things can get canceled or modified, delayed [or] need to go to a different location depending on the ice conditions for the year. And with these changes we’re seeing in ice over time, we’re gonna have more and more of that.

You and your colleagues also look at other services ice offers, including — this is around the world sometimes and over history — ceremonial or religious benefits. That’s something I hadn’t thought of. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

One really long-standing tradition is in Japan — Lake Suwa — where there’s been ice records since 1443 by Shinto priests to document the formation of an ice ridge. That ice ridge appearance is thought to be a message from [a] god, so the bridge is formed by the footsteps of one god crossing the lake to visit another god. So then that starts a ceremonial process.

They’ve been keeping these records since the 1400s, just for their religious purposes, not for any scientific reason. But then some scientists — from the University of Wisconsin-Madison — were able to take advantage of that to relate it to climate change, and then we explored it a little bit further in our study.

Bringing things closer to home, you’re able, based on where you are, if nothing else, to talk to people about how they feel the impact of not as not as much ice fishing or these event cancellations. What do people say? How do they talk about this decline of ice if they notice it?

A lot of times, I hear more thinking about the past and and how they used to be out ice fishing in this area by Thanksgiving really reliably, and now that’s not such a sure thing. So I hear that sometimes. But I don’t often hear that next step of going to climate change. So I think that’s kind of interesting, but I think our study sheds light on taking it to the next step.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.