The head of the Environmental Protection Agency said federal regulators are committed to finalizing national drinking water standards for PFAS by the end of the year.

In March, the federal agency proposed regulations for six PFAS or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. The EPA is planning to set individual limits for the two most widely studied PFAS chemicals — PFOA and PFOS — at 4 parts per trillion. That’s more than 17 times lower than Wisconsin’s drinking water standard for PFAS of 70 parts per trillion. The EPA wants to regulate a mix of four other PFAS, including PFNA, PFHxS, PFBS and GenX chemicals.

EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan said during a stop in Eau Claire on Wednesday that the harmful so-called “forever chemicals” exist in many places where they shouldn’t be found, but the agency doesn’t want to set regulations that appear to target farmers and water systems.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“As we design health-based standards to protect public health and the environment, we’re also going to use our discretion to ensure that we focus on those who have put this pollution in the environment, not on our farmers and not on our water utilities,” Regan said.

PFAS are a class of thousands of synthetic chemicals widely used by industry since the 1940s. They’ve been used in everyday products like nonstick cookware, stain-resistant clothing, food wrappers and firefighting foam. The chemicals don’t break down easily in the environment. Research shows high exposure to PFAS has been linked to kidney and testicular cancers, fertility issues, thyroid disease and reduced response to vaccines over time.

Kevin Krentz, president of the Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation, said during a roundtable discussion with Regan and federal officials that Wisconsin needs funding to research health threats related to the chemicals and strategies for reducing those risks.

“Farms across the state provide the ability for municipalities to spread municipal (sewage) sludge. Those PFAS are not produced on the farms, but farmers can carry a big risk for that PFAS,” Krentz said. “Not holding farmers liable for that PFAS is extremely important moving forward as well.”

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has said around 60 percent of 580 municipal wastewater facilities spread sewage sludge, known as biosolids, on land in any given year. The agency’s interim strategy for the material states around 85 percent of all biosolids generated are reused on land for nutrients.

Republican lawmakers have echoed concerns about the risks posed to farms with PFAS contamination. They created a $125 million fund to address the chemicals under the 2023-25 state budget. State Sens. Robert Cowles and Eric Wimberger and Reps. Jeff Mursau and Rob Swearingen have authored a bill that outlines how the money would be spent. Wimberger has said farmers and other landowners are reluctant to test for PFAS because they face the risk of being financially destroyed if ordered to clean up the chemicals.

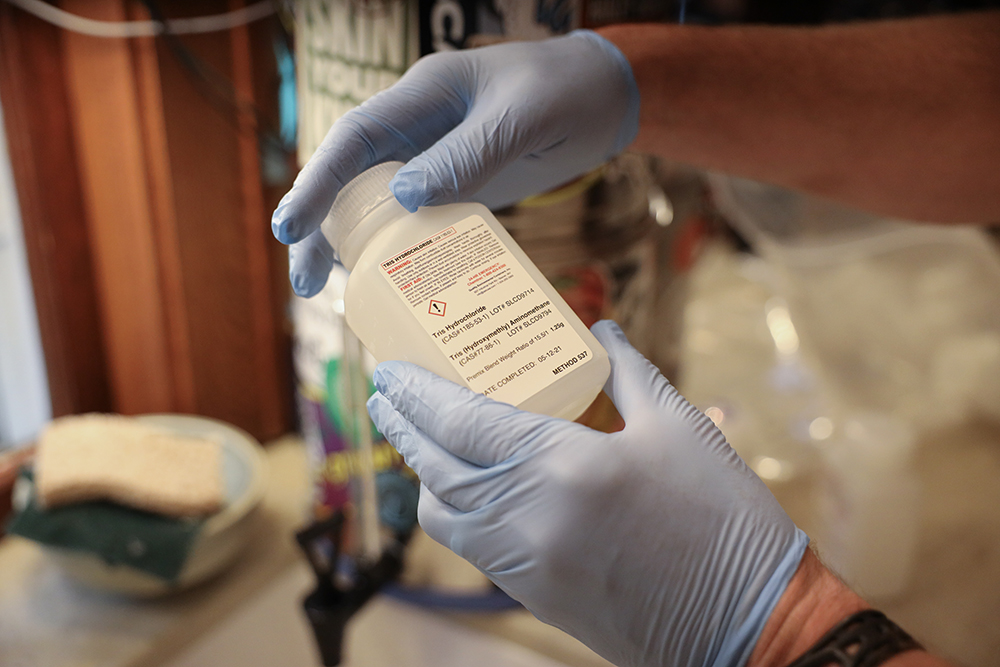

Photo courtesy of Sen. Wimberger’s office

The GOP proposal creates a grant program to help municipalities and landowners test for PFAS in their water, but it would also restrict the ability of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to test and clean up the chemicals on private property. The DNR wouldn’t be able to require a property owner to test for PFAS unless it had reason to believe levels would exceed state or federal standards. A Senate committee advanced the bill, but it’s yet to be scheduled for a vote by the full Senate.

As the EPA finalizes limits for the chemicals, water groups have highlighted concerns over the cost of complying with more stringent standards. The American Water Works Association estimates treatment of PFAS in drinking water could cost up to $38 billion. In small communities, advocates for rural Wisconsin water systems say the cost to replace a contaminated well may run up to $2 million, and treatment may be even more costly.

Chris Groh, executive director of the Wisconsin Rural Water Association, said the EPA should provide more money to water utilities and farmers if federal regulators are going to set more restrictive standards. Earlier this year, the agency awarded $25 million to Wisconsin as part of $5 billion that’s being awarded over five years under the bipartisan infrastructure law to help communities reduce PFAS in drinking water.

Even so, Groh said he fears that water utilities and their customers will be on the hook to pay for treatment.

“It should come down to the manufacturer or the user if they knew there was PFAS in the products,” Groh said. “Everything we’ve seen, as far as getting into the water streams or water utilities, has come from outside sources like industrial use or the firefighting (foam) use or things like that. It’s nothing brought on by or used by water utilities, so it’s not fair to ask them to pay for removing it.”

Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, the state’s largest business group, declined to comment on the EPA’s regulations Thursday. The group has previously said the agency’s proposed standards appear to “go far beyond any reasonable criteria for regulating PFAS.”

Communities across Wisconsin have been struggling with PFAS contamination in public and private wells. They include the towns of Peshtigo and Campbell along with the cities of Marinette, Eau Claire, Wausau, Madison and Milwaukee. The DNR has identified PFAS contamination at nearly 100 sites where cleanup of the chemicals is ongoing.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.