One northern Wisconsin tribe that had signed up to receive the COVID-19 vaccine through the state has since shifted to getting doses through the federal Indian Health Service after facing uncertainty regarding when shipments would arrive.

Tribes were able to choose whether they would receive vaccines through the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS) or the federal Indian Health Service that provides health care for around 2.6 million American Indians nationwide.

The St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin signed up to receive the vaccine from the state after DHS opened enrollment in November.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

State health officials notified the tribe that it had received its application. But, tribal health officials felt left in limbo about when they would begin receiving doses, according to St. Croix Health and Human Services Director Jackie Lowe.

“It was just whoever could get them to us first, I suppose, is why we switched,” said Lowe.

The tribe began receiving the vaccine from IHS in early January. Lowe said that’s around the same time St. Croix would’ve received doses from the state, but she felt there was more clarity from IHS over the distribution and whether tribes would be able to exercise their sovereignty in decisions regarding who should be vaccinated.

Lowe had expected the tribe would receive a total of 400 Moderna doses by the end of last week.

“With IHS, there was no question that the tribe gets to select who they want to set as priority; whereas the state, it felt like maybe we have to follow those (CDC) guidelines,” said Lowe.

The St. Croix tribe is not the only tribe facing uncertainty with the state’s vaccine rollout. Dr. Amy Slagle, medical director at the Menominee Tribal Clinic, said some members are questioning the pace of vaccination compared to tribes who went with Indian Health Service.

DHS had sent 200 doses of the Moderna vaccine to the Menominee tribe by the end of the first week in January, and Slagle said it wasn’t clear they would receive more the following week. But, on Jan. 11, tribal officials scrambled to organize vaccination when they learned the state was sending another 200 doses. Slagle said the vaccine arrived a few hours after they were notified.

She said she knows the state’s task is “Herculean” and believes they’re giving the tribe as much attention as any other community.

“That said, if you look at the DHS map of disease burden in the state, Menominee County sticks out like a sore thumb … From my viewpoint, getting vaccine done as quickly as possible is of utmost importance,” said Slagle.

The county was one of three in the state that had “critically high” COVID-19 activity in the first two weeks of January. Since then, virus activity in the county has improved slightly. Still, state data shows Indigenous communities in Wisconsin experience higher rates of COVID-19 cases, and they’re hospitalized at a rate nearly two times that of their white counterparts. Death rates among American Indians in Wisconsin from COVID-19 are 1.4 times greater than white residents.

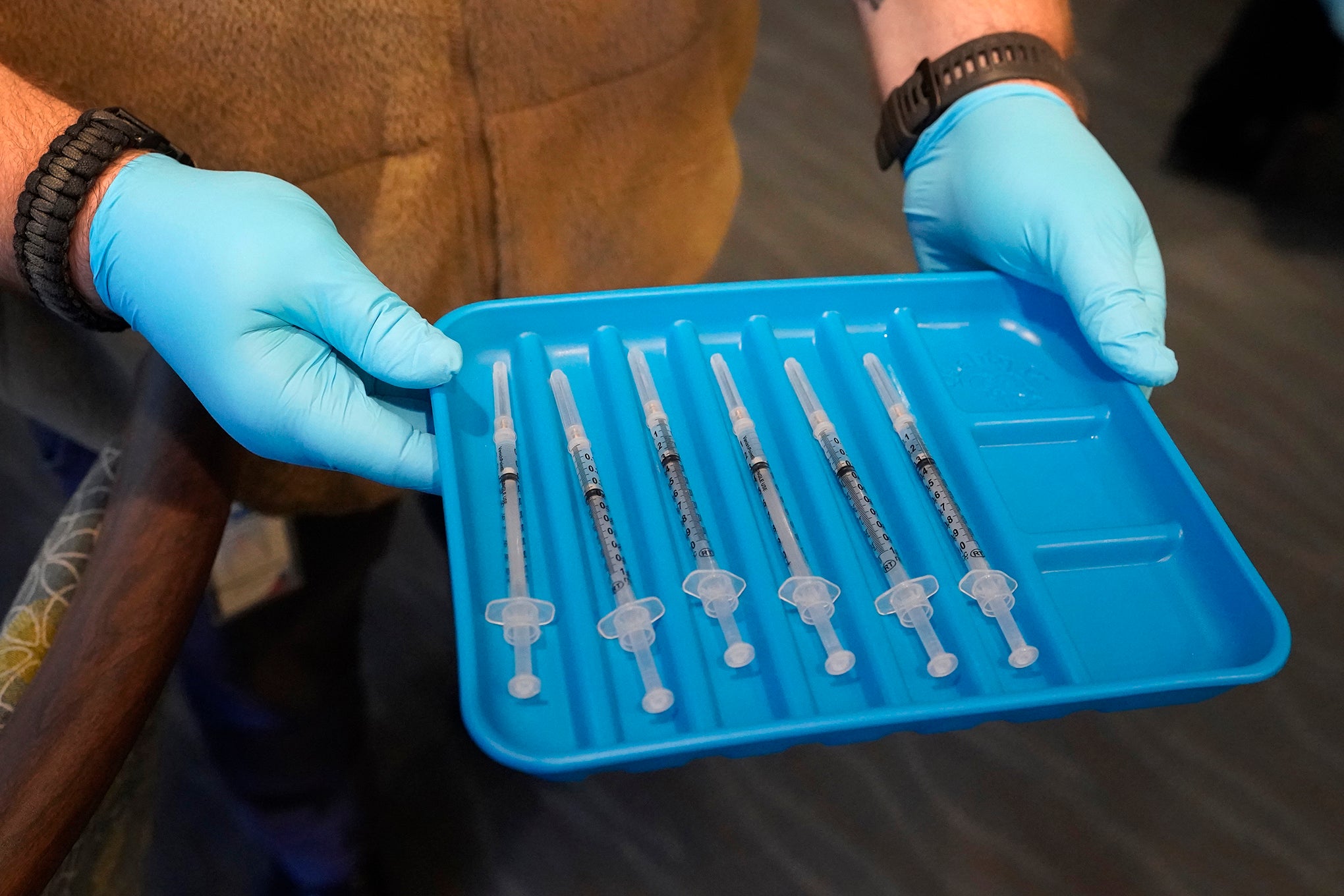

Photo courtesy of Indian Health Service

A DHS spokesperson said in an email that four Wisconsin tribes have requested vaccine from the state and said they’re hearing tribes are satisfied with the vaccine supply so far “as long as it keeps coming.”

Since mid-December, the state has administered around 310,000 doses of vaccine statewide. Wisconsin’s rollout of the vaccine has lagged behind neighboring states, prompting criticism from Republican lawmakers. State health officials have said demand exceeds supply from the federal government.

Gov. Tony Evers and his administration have called on federal officials to increase doses the state receives and provide better forecasts of allocations for planning. Wisconsin Deputy Health Secretary Julie Willems Van Dijk has said the state expects to receive around 70,000 doses each week, pleading for patience among residents.

The Oneida Nation opted to receive vaccine from DHS because they wanted to utilize existing partnerships with state and local health officials, according to Debbie Danforth, comprehensive health division director for the Oneida Nation. She wouldn’t say how many doses of the vaccine they had received, citing security concerns. But, Danforth said the tribe was still in the process of vaccinating the 353 health care workers within their comprehensive health division last week.

She said tribal health officials have a good working relationship with the state and pointed to difficulties with mass production of the vaccine.

“We’re hopeful with the new presidential administration that we’ll see some changes in terms of the amount of vaccine availability,” said Danforth. “Other tribes are having the same issues, whether they’ve gone with IHS or whether they’ve gone with the state.”

Indian Health Service, like states, is unable to plan more than a week in advance as to how many doses it will receive for distribution, according to IHS Bemidji Region Director Daniel Frye.

“For any health administrator … that’s just hard,” said Frye.

Frye said the St. Croix tribe is the only tribe in the Bemidji Region to make the switch so far. Around 340 tribal health programs and urban Indian organizations have chosen to receive the vaccine through IHS nationwide. The agency is distributing doses to the Gerald L. Ignace Indian Health Center in Milwaukee and seven Wisconsin tribes, including St. Croix, Lac Courte Oreilles and Red Cliff.

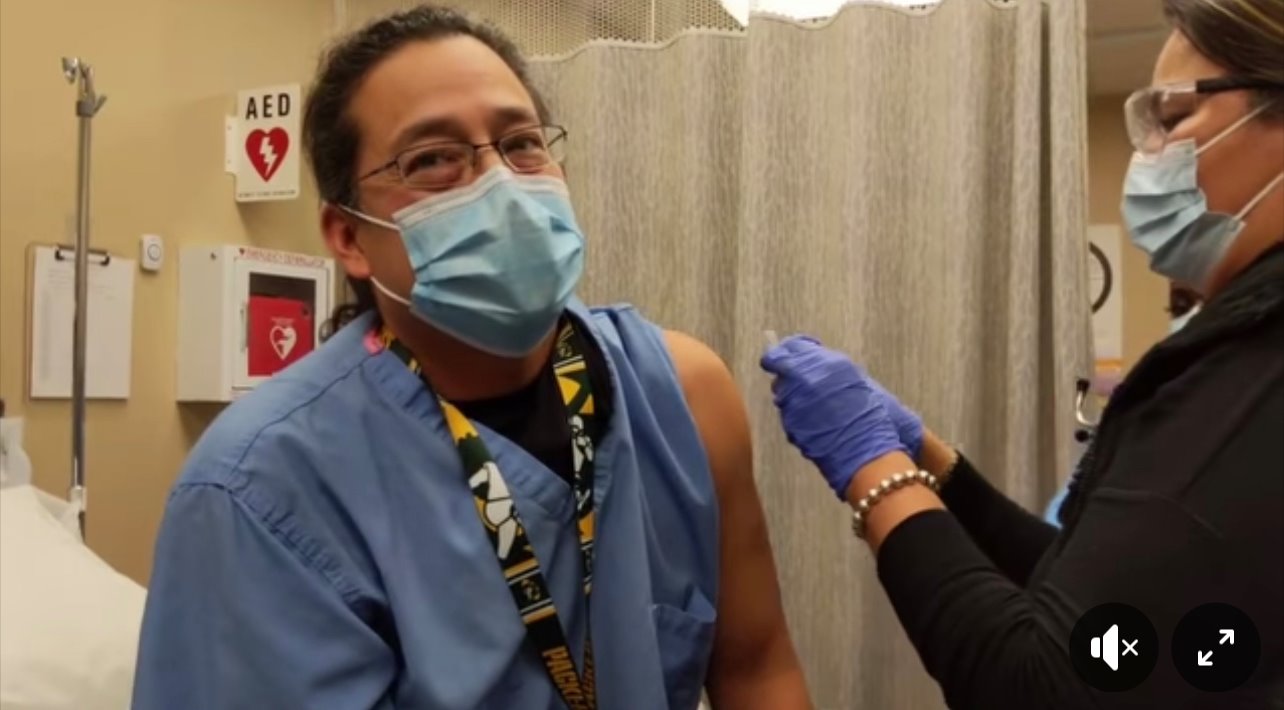

Photo courtesy of Indian Health Service

IHS has partnered with the U.S. Coast Guard to fly vaccine through Wisconsin and Michigan to overcome issues with storage of the Pfizer vaccine, which must be kept at arctic-like temperatures. The agency has also used the Civil Air Patrol to ship booster shots to tribes. Frye said the agency had received around 12,500 doses by mid-January for the Bemidji Region, which includes federally recognized tribes and organizations in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin.

Tribal health officials for the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa say IHS has been instrumental in coordinating vaccine shipments there, according to Bryon Daley, the tribe’s environmental health specialist. As of last week, the tribe had received 465 doses of both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines combined.

But Red Cliff tribal health officials are worried about staffing as the vaccine becomes more readily available, according to Diane Erickson, the tribe’s health services administrator. She said they’re looking to recruit retired nurses.

“If we do get a substantial amount of supply, we have a plan to shut down primary care and use our doctors and our medical providers to do vaccines,” said Erickson.

Slagle with the Menominee Tribal Clinic said they’re also considering the possibility that they may not be able to provide as many clinic appointments if people need to be pulled in to deliver vaccine. She said they would likely draw from EMTs in the region or reach out to the Wisconsin National Guard for help. The state recently announced it would deploy mobile vaccination teams to assist local and tribal health officials with limited resources to coordinate vaccination.

In the meantime, Slagle said elders are clamoring for the vaccine. She has faith that state health officials are doing everything they can to allocate doses as quickly as possible.

“We will hang in there and wait,” said Slagle. “And we’ll give vaccine when we get it.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.