In 2017, Dan Wegmueller, a fourth-generation farmer and owner of Wegmueller Farms, was on the brink of bankruptcy. It wasn’t until he converted his farmhouse into an Airbnb and expanded into agritourism, that his business got back on track.

“It’s brought in a revenue stream that we desperately needed to keep the farm going. But it’s also made farming fun again,” Wegmueller said.

While his business was struggling, Wegmueller was also dealing with the loss of his parents. He said it was a lot to manage.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Wegmueller was able to turn things around, but he said he’s seen other farmers struggle, as western Wisconsin leads the nation in farm bankruptcies.

He said that stress can take its toll on farmers’ mental health and it makes him wonder: “Why is rural mental health such a big issue? Now, in this day and age?”

He and other farmers grapple with those questions with Farm Well Wisconsin, an organization that aims to support the well-being of farmers, farm workers and their families. It’s an extension of an anti-poverty agency called the Southwestern Wisconsin Community Action Program, which covers Grant, Green, Iowa, Lafayette and Richland counties.

Now, Wegmueller attends regular meetings and connects with farmers about his own experiences through the group.

“We need to protect programs like this for the simple fact that it gets people talking. Nobody’s alone in this,” he said.

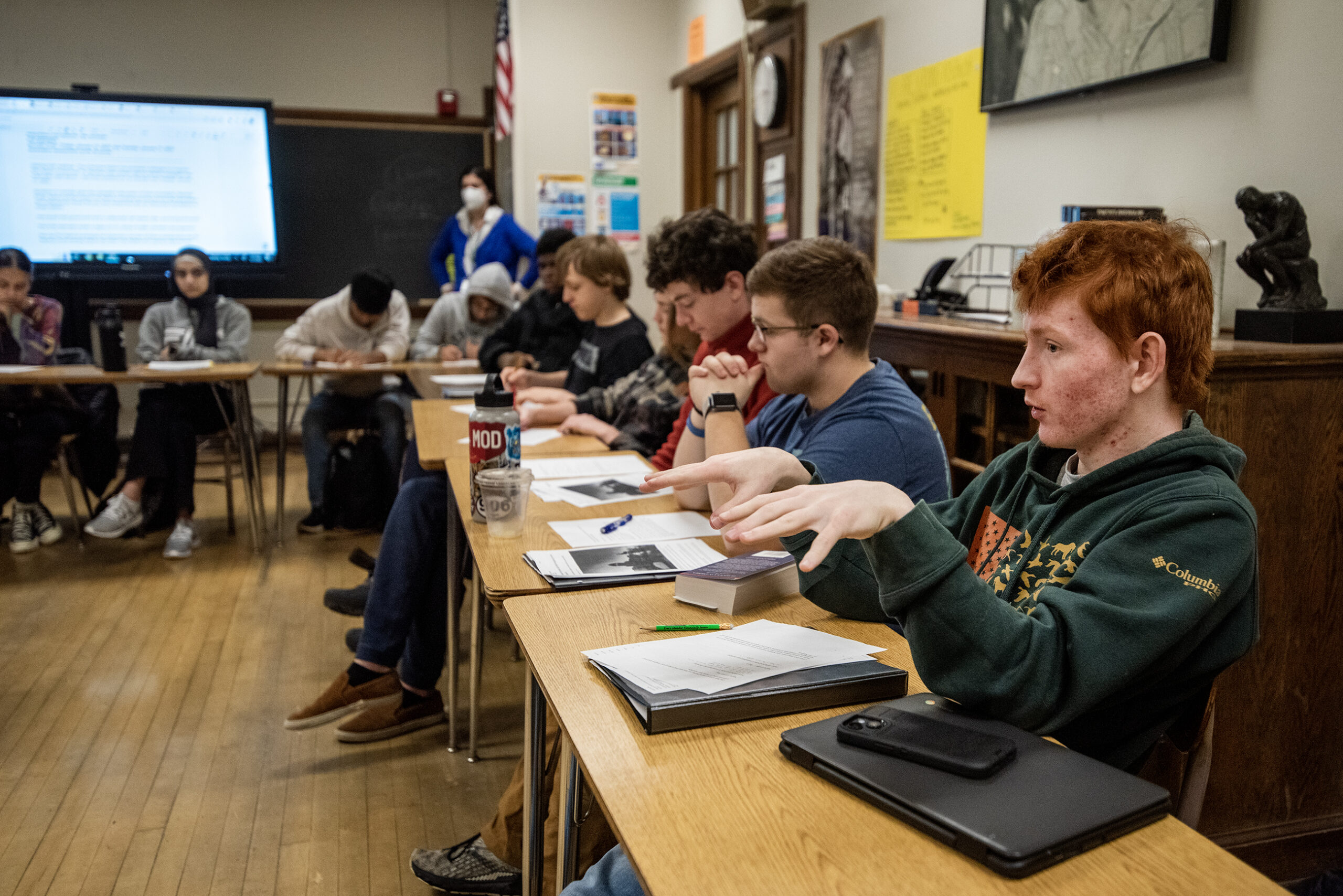

The group, founded in 2020, is funded through a five-year grant associated with the Wisconsin Partnership Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health. Through trainings, community members work on building empathetic listening skills, connecting people with resources and discussing issues related to farm culture.

Farm Well Wisconsin Founder Chris Frakes said she grew up during the farm crisis of the 1980s in southeast Iowa, where she saw firsthand how an economic downfall affected the mental health of farmers and their families.

“In my particular community, we had a couple of farmers die by suicide in the 1980s. And my uncles, who were farmers, really struggled economically, nearly lost the family farm,” she said.

“I saw the toll that that took on farmers and farm families, combined with the way that farmers and farm families tend to be very stoic. And so they don’t have very well-developed internal resources to talk about when they’re really stressed or struggling,” Frakes continued.

Years later, the dairy industry took a blow amid what Frakes coined a “farm downturn” in 2018, part of what pushed her to start Farm Well Wisconsin.

For David Unbehaun, a self-described “recovering dairy farmer,” and the co-owner of Unbehaun Acres in Richland County, suicide prevention is an all-too-familiar cause to support.

“Farmers are some of the most independent people that will do whatever they can not to ask for help. I think it just goes with the territory,” he said. Unbehaun said he knew two or three people that died by suicide in the last decade.

For Wegmueller, some of the stress farmers are dealing with today comes from the commodification of the industry. He said large-scale, mass production and industrialization of farming has pushed farmers into the mindset that bigger is better.

“As farmers, we’ve lost track of who we are. We’ve lost track of our role on the farm and our role in society. Farmers don’t produce food anymore. We produce commodities,” he said.

Farm Well Wisconsin focuses on suicide prevention, community resources

Shawn Monson works with Farm Well and leads a training focused on helping people before they’re in a mental health crisis.

“We give you the skills and the training to engage in a conversation that shows that you genuinely care and want to hear how somebody’s doing, how to listen to them, you know, validate what they’re experiencing,” he said.

The group also runs “SafeTalk,” a program to help people identify signs of someone struggling with suicidal thoughts.

Monson said getting farmers to talk through their issues and validate their experiences goes a long way in bettering their mental health.

Frakes emphasized that asking for help is a sign of strength.

“We’re not trained psychologists or psychiatrists. But we are well-trained lay people who can talk to rural neighbors about the importance of taking care of mental health,” Frakes said.

Unbehaun, the Richland County farmer, said that anytime he hears that someone has died by suicide he wonders: “Could I have helped them?”

“We may not answer all the questions, but at least we’re trying,” Unbehaun said.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, call or text the three-digit suicide and crisis lifeline at 988. Resources are available online here.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.