Lambeau Field.

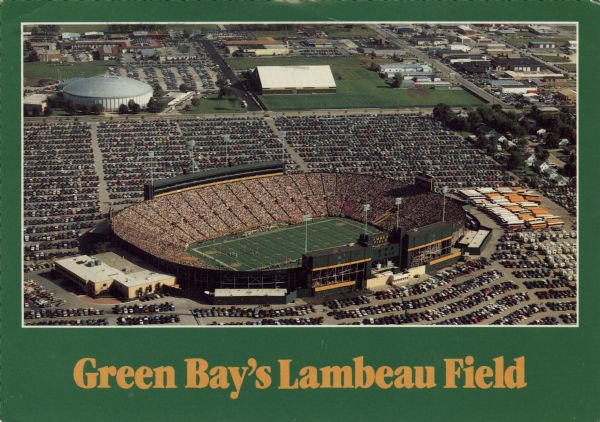

It’s the land of Green and Gold and the Lambeau Leap.

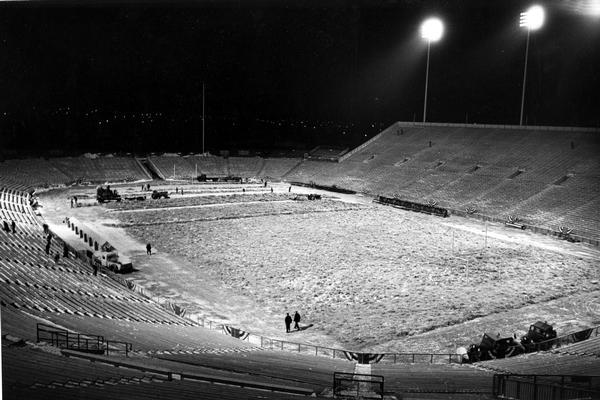

It’s ranked the most iconic NFL stadium in the country time and time and time again. The old school stadium looks good in freezing temperatures, as a snow globe and at sunset.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

It even has its own Facebook, Instagram and Twitter accounts.

And it’s located … where? That’s the question Wisconsin Public Radio’s WHYsconsin received years ago.

It was Nov. 10, 2019 — hours before the Green Bay Packers would take the field and triumph over the Carolina Panthers. WHYsconsin was at a chilly tailgate outside Lambeau Field asking people what questions they have about our state, and one woman asked: What city is Lambeau Field actually located in?

The answer seems obvious, the Green Bay Packers play at a stadium in Green Bay. The address is a Green Bay address. Parcel maps show the stadium is in Green Bay.

But if you live in the Green Bay area (or look at the maps) you may notice that three sides of the rectangular plot of land the stadium sits on — South Oneida Street, and South Ridge and Valley View roads — border the Village of Ashwaubenon; the fourth — Lombardi Avenue — borders the City of Green Bay. On a map, it looks as if this sliver of land was purposely cut out of the village — and it was, sort of.

The real answer to this WHYsconsin question is easily found. The Frozen Tundra is in the City of Green Bay and not the Village of Ashwaubenon; however, the history behind the answer is arguably the interesting part.

“The whole story about the selection of that site is fascinating in itself, not just the fact that it was in Ashwaubenon and it ended up in Green Bay,” said Cliff Christl, official Green Bay Packers historian and author of the book “The Greatest Story in Sports.”

There is a chapter devoted to the stadium’s site selection in the four-volume book.

“The political wrangling that went on back in the ’50s over whether it was going to be built on the East Side or West Side. I mean, that was a bitter battle,” Christl said. “There were fears that Green Bay might lose the Packers because the East Side-West Side battle would never end.”

As PackersNews.com put it, at the time of stadium talks, the Packers were not a powerhouse and “the city needed a new stadium. Its future with the Packers depended on it.”

The city either needed to build a new stadium or lose the Packers, that’s according to a Green Bay Press-Gazette clip from March 14, 1956:

Do Green Bay residents value the Packers enough to add 22½ cents per $1,000 assessed valuation to their tax bills for the next 20 years? When all the votes are counted April 3 the answer to this question will write the result of the bonding referendum. While it would be unfair to discard the strictly city needs for a new stadium, it has been made plain that the continuing of professional football in Green Bay depends upon a plant with greater seating potential and more salable seats… All taxpayers can find occupational, recreational or civic reasons for standing to gain in varying degrees from Green Bay being a “big league” sports city.

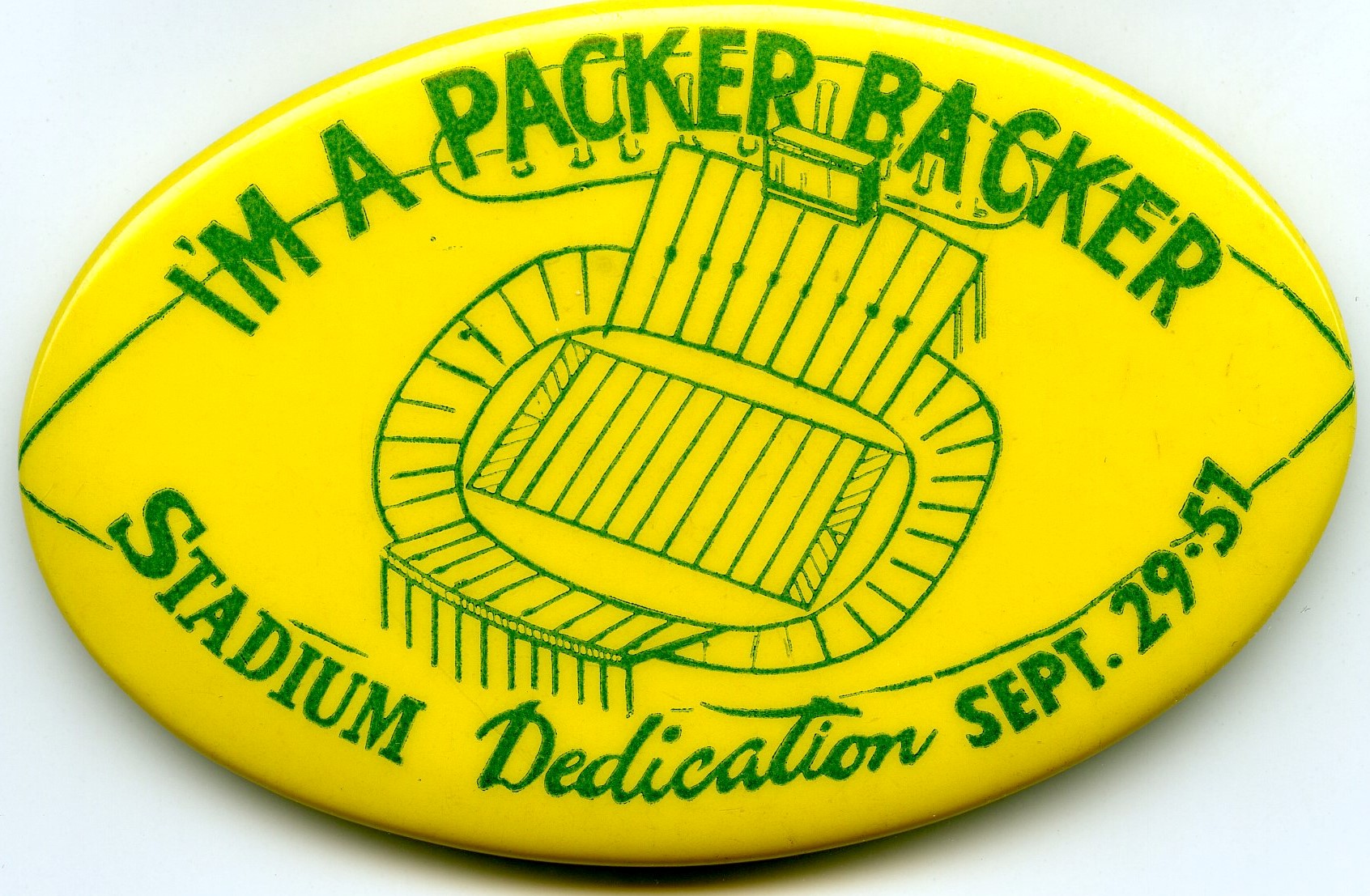

Lambeau Field, originally called Green Bay City Stadium and renamed in 1965, hosted its first game Sept. 29, 1957 against the Chicago Bears. It was considered the first stadium built exclusively for a professional football team, Christl said. The stadium in southwest Green Bay could seat 32,000-plus people and was surrounded by a chain-link fence. Surrounding it was farmland. But the years leading up to this moment were rocky when it came to local politics and the new stadium.

East versus West

The Green Bay City Council, Packers organization and the NFL had been discussing the need for an improved stadium for years before an April 3, 1956 bonding referendum passed, approving $960,000 to build a new Packers stadium. The cost would be split between the city and the Packers.

But there was a snag in the progress: The 24-person council — evenly divided between the East and West sides of Green Bay — couldn’t agree on a site for the stadium, Christl said. With the City Council unable to get on the same page, the Green Bay Packers organization stepped in shortly after the referendum passed and hired an outside consultant, Osborn Engineering Co. of Cleveland, Ohio. The company surveyed more than a dozen sites.

There is a long, fierce rivalry between the two sides of Green Bay, Christl said.

When Green Bay East and Green Bay West high school football games happened there were fights and fires were set. Christl remembers times when people wouldn’t cross from one side of town to another. When it came to the new stadium, each side had their own strong opinions and didn’t plan on backing down.

In a 2017 article, Christl explained that the two proposed sites were the existing football stadium behind East High School — called City Stadium — preferred by the East Siders, and Perkins Park, on the city’s northwest side, preferred by the West Siders.

Christl said there was a time when fixing up and expanding City Stadium (eventually referred to as old City Stadium) was the primary option, but one West Side alder, Leonard Jahn, kept pushing for something that allowed for more growth. His opinion spread among the other West Side alders, and the site debate became an East Side versus West Side disagreement, and eventually led to Osborn Engineering being hired.

The historian said Osborn Engineering took several things into account when searching for the perfect location, including future expansion, proximity to the highway, parking and slope for the bowl.

Ultimately, the company said the plot of land known as the Ridge Road-Highland Avenue location, in the Town of Ashwaubenon, was the right pick. The property for the stadium was 48 acres, owned by Victor Vannieuwenhoven and on the West side of Green Bay. It was ultimately purchased for $73,305 in August 1956. The land was annexed from the Town of Ashwaubenon in September 1956.

“I’ve never come across anything where newspapers of the day and the coverage of the day where it said that Ashwaubenon resisted the annexation,” Christl said.

Part of the brochure for the first game the Green Bay Packers played at Lambeau Field, originally called Green Bay City Stadium and referred to as new City Stadium. The game was held Sept. 29, 1957 against the Chicago Bears. Image courtesy of Dennis Sell

Part of the brochure for the first game the Green Bay Packers played at Lambeau Field, originally called Green Bay City Stadium and referred to as new City Stadium. The game was held Sept. 29, 1957 against the Chicago Bears. Image courtesy of Dennis Sell

Another factor that led to the annexed farmland choice were local alcohol regulations.

There was speculation that the Perkins Park location fell under an ordinance that wouldn’t allow for the sale of beer. At the time, the Town of Ashwaubenon was dry. So if the stadium was built in the town or at Perkins Park, there was concern that no beer could be sold — and with Wisconsin’s long history with alcohol, a stadium with no beer likely wasn’t an option.

“Had they not annexed the property, that too could have been an issue,” Christl said. “But because the mayor, Otto Rachals, at the time decreed that because this property was being annexed from Ashwaubenon, it would not be covered by that ordinance … One benefit at the time of the construction of the stadium was that the Packers would be able to sell beer there, and obviously in Green Bay or anywhere in Wisconsin, that would be a must.”

Once a site was selected, the timeline seems swift: Christl said the company determined the site in July 1956, land surveying happened by October, construction started in February 1957 and the stadium hosted its first game seven months later.

When construction first began, there was an expectation that the stadium would have about 20,000 permanent seats and 12,000 temporary seats, but with money saved by building the stadium into the ground, 32,154 permanent seats could fit, he said.

And while there was more room for parking at the new City Stadium than the old one, there was a farm in the parking lot until 1963. The Vannieuwenhoven family didn’t want to give up their home when they sold the rest of the land for the stadium.

“When you parked your car in the West Side of Lambeau, you might have been parking near a barn and maybe some chickens … Only in Green Bay,” Christl said.

This story was inspired by a question shared with WHYsconsin. Submit your question below or at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it.