After more than two decades, the U.S. Department of Education is lifting restrictions that prevented incarcerated people from using a type of federal aid to pay for college.

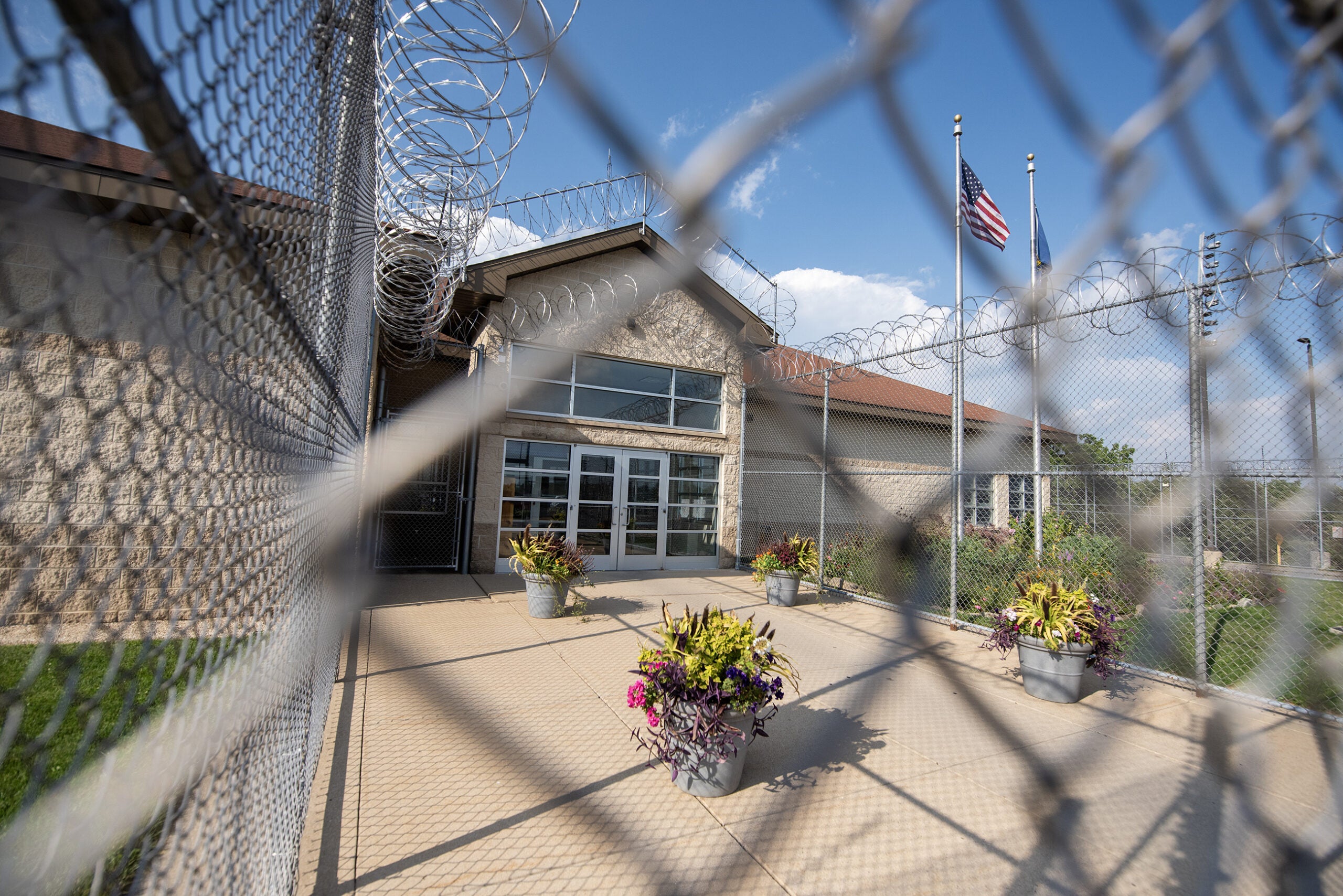

The change could bring additional opportunities to Wisconsinites behind bars, as colleges take steps to expand their programming inside the state’s prisons.

More than 6 million low-income students across the country used Pell grants to help pay for higher education in the 2021-22 school year. But a provision in a 1994 U.S. crime bill has banned incarcerated students from using those federal grants.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“It was really part of our nation’s larger kind of tough on crime stance at the time,” said Margaret diZerega with the Vera Institute of Justice, a think tank that researches mass incarceration. “It’s terrific to see this law change given what we know about the benefits of college in prison, in terms of reducing the likelihood of someone returning to prison (and) reducing violence in prisons, which makes it safer for the people who live there, and the people who work there.”

Following a vote from Congress in 2020, those restrictions were lifted effective July 1. The change is long overdue, said Roy Rogers, who advocates for criminal justice reform in Wisconsin though a group called The Community.

“For many, many years, this door of opportunity has been closed to many men and women,” Rogers said. “Since this opportunity is reestablished, it’s going to create hope. It’s going to create a mindset that says, ‘You know what, since I do have this opportunity, I don’t want to do anything that’s going to jeopardize it.’ So it will affect the behavior of the men and women on the inside.”

Since 2016, some people in Wisconsin prisons have been able to get federal aid for college as part of a pilot called the Second Chance Pell experiment. Currently, those classes are offered online as part of partnerships with three institutions — Madison College, Moraine Park Technical College and Milwaukee Area Technical College.

Outside of Second Chance Pell, other programs, such as Odyssey Behind Bars through the University of Wisconsin, are made possible by a mix of state funding and private donations, said Ben Jones, who oversees educational programs for the Wisconsin Department of Corrections.

Last semester, 350 of the 464 students taking classes through the Wisconsin DOC were part of Second Chance Pell, Jones said.

Now that the 1994 restrictions have been lifted, diZerega anticipates more incarcerated students will be able to pursue higher education in Wisconsin and across the country.

“It means that we should see a real expansion of college programs in prison,” she said.

So far, two colleges that already participate in Wisconsin’s Second Chance Pell — Madison College and Moraine Park Technical College — have responded to the DOC’s initial request for information, indicating they want to offer programming under the expanded Pell criteria, Jones said.

The new programs still need to undergo a multi-step approval process involving accrediting agencies and the Department of Education. It’s not yet clear how soon expanded Pell offerings could become available inside Wisconsin prisons.

At Madison College, instructors currently offer an associate’s degree in entrepreneurship through Second Chance Pell. Officials there have submitted paperwork to add a liberal arts transfer program as well as business management associate’s degree for people inside Wisconsin prisons.

Shauna Rasmussen, the college’s dean of early college and workforce strategy, hopes the expanded Pell programs can be up and running by the 2024-25 school year.

“I think that because Madison College has been a Second Chance Pell college, it will be a lot easier for us to just transition,” Rasmussen said. “We’ve seen what education can do in terms of their ability to secure employment and really great wages.”

Bobby Ayala was sentenced to Wisconsin prison after pleading guilty to homicide-related charges in 1994, the same year the Pell ban took effect. He says he was eventually able to take some computer classes while he was incarcerated, but wishes he had more opportunities.

“I went in there angry — angry at myself, angry at the word, angry at the system,” said Ayala, who was paroled in 2020 and now advocates against mass incarceration as a fellow with Ex-Incarcerated People Organizing Wisconsin. “When you’re isolated and lonely like that, you need some type of programming. You need something to do, and that was taken away from me.”

Once the Pell expansion begins, the U.S. Department of Education estimates 30,000 incarcerated students nationwide could receive $130 million in total aid per year. That compares to more than $26 billion allocated from Pell grants in the 2021-22 school year.

Jones, of the Wisconsin DOC, says there are societal benefits to offering higher education to people who are in prison. One 2016 report from the RAND Corporation found that people who participated in an educational program while in prison were less likely to return to prison after reoffending.

“Other people say, ‘Well, why are you getting a free college education when you’re incarcerated?”‘ Jones said. “What we like to say is there’s about 95 to 96 percent of the folks who are sitting in our prisons in the state of Wisconsin are going to return back to the communities that they came from someday.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.