Wisconsin’s manufacturers have been dealing with the global shortage of semiconductors, but the federal CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 could change that.

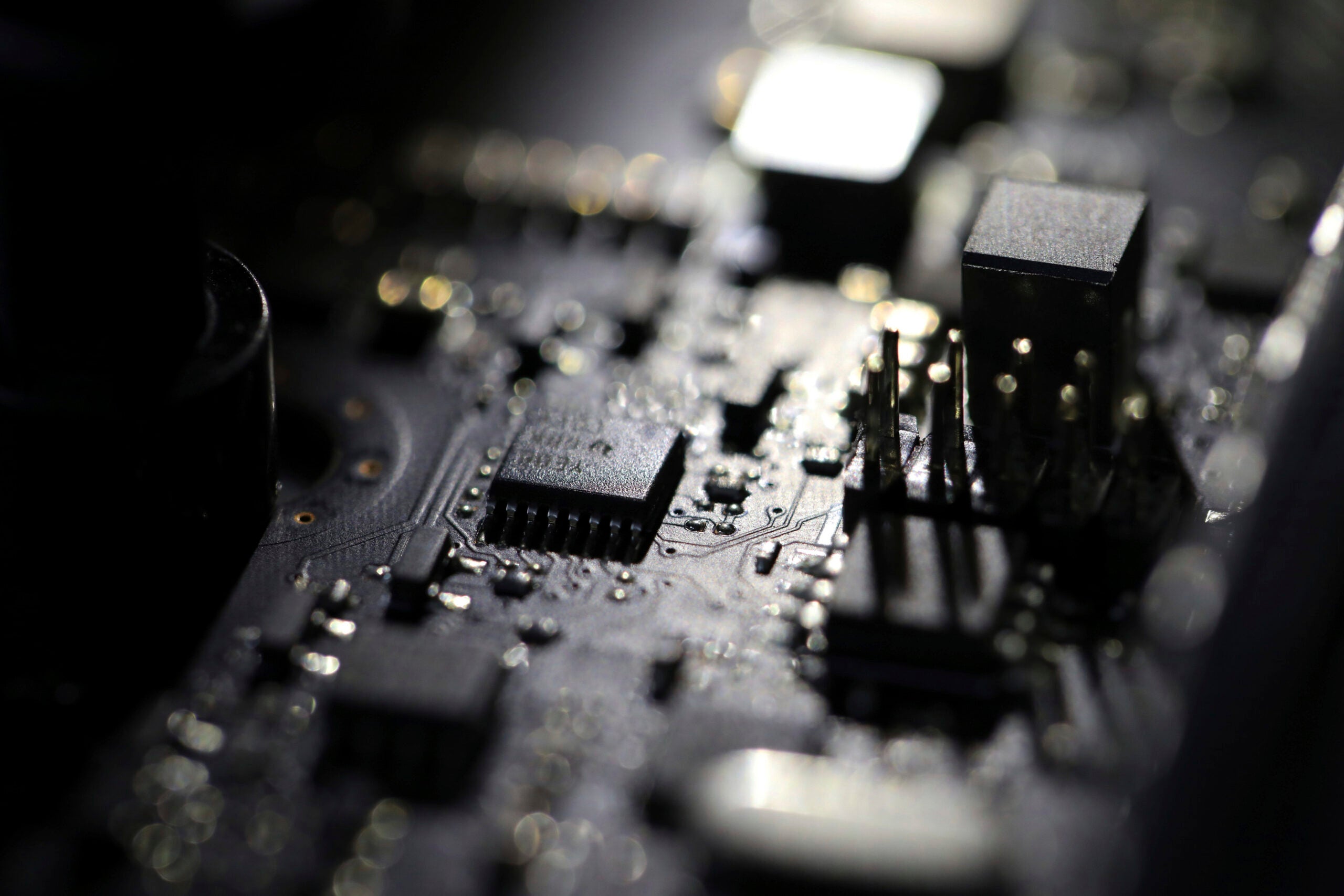

Semiconductors, or microchips, can be found in just about every electronic device from cell phones to cars, and have become essential for both the U.S. and state economy.

“In 90 percent of technology we rely on every day in our life, you can find at least one of those simple microchips,” said Behzad Bahraminejad, an instructor of electrical engineering at Fox Valley Technical College.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But the chips have been in short supply in recent years, hampering Wisconsin manufacturers that produce products requiring semiconductors.

One such company is the Fond du Lac-based Wisconsin Lighting Lab, which makes LED lighting, light poles and wireless lighting controls.

“Every single product that we ship on the lighting side will have at least one semiconductor,” said Adam Rupp, president of the Wisconsin Lighting Lab.

He said the supply shortage has diverted attention from research and development, as well as other necessary aspects of business, which was “especially difficult for small companies.”

“As much as 50 to 60 percent of our time, the last two to three years, has been spent on supply chain and supply chain-related issues,” Rupp said. “How many Thanksgivings and Christmases do you remember where people were talking about supply chains around the dinner table? That has really happened every holiday that I’ve been to the last couple of years.”

To combat the semiconductor shortage, Congress passed the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, which President Joe Biden signed into law last August. The law allocates $52.7 billion for American semiconductor research, development, manufacturing and workforce development.

Although semiconductors were invented in America, the country only produces about 10 percent of the world’s supply. More than 60 percent of all the world’s chips come from Taiwan, according to Buckley Brinkman, chief executive of the Wisconsin Center for Manufacturing and Productivity.

Brinkman said the main benefit the CHIPS and Science Act has for Wisconsin comes from ensuring manufacturers a more reliable semiconductor supply.

“We have a lot of companies that use the chips,” he said. “We’re the folks that are building the components for those larger products.”

Rupp said he would welcome increased domestic supply.

“Anytime you can increase your supply options and local options — assuming the quality, the pricing and everything (else) is competitive — it’s going to be a good thing,” he said.

While the state’s manufacturers could be bolstered by increased supply, Brinkman said it’s unlikely the state will secure a semiconductor fabrication facility, or “fab,” as part of the legislation.

He said requests for proposals will come out next month, but he anticipates government funds for semiconductor production will be tied to having facilities built and having other sources of funding to complement the federal money.

“We don’t have that kind of proposal built up for that, here in Wisconsin,” Brinkman said. “There are places that are making a concerted, coordinated approach to that. … That’s what it’s going to take to bring an actual fab to Wisconsin.”

Had Wisconsin managed to attract an Intel chip-making hub to its Foxconn site in Mount Pleasant, Brinkman said, the state’s chances of receiving federal funding for a semiconductor fabrication site would have been improved. Instead, the company chose to locate its $20 billion facility in Ohio.

Even so, Harry Moser, president of the Reshoring Initiative, a nonprofit that promotes bringing manufacturing back to America, said the CHIPS act still has the potential to benefit Wisconsin.

“If you can’t build the chips, then assemble the electronic systems for which the chips are necessary. That could happen anywhere in the country,” he said. “That would seem like a logical thing for Wisconsin to do.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.