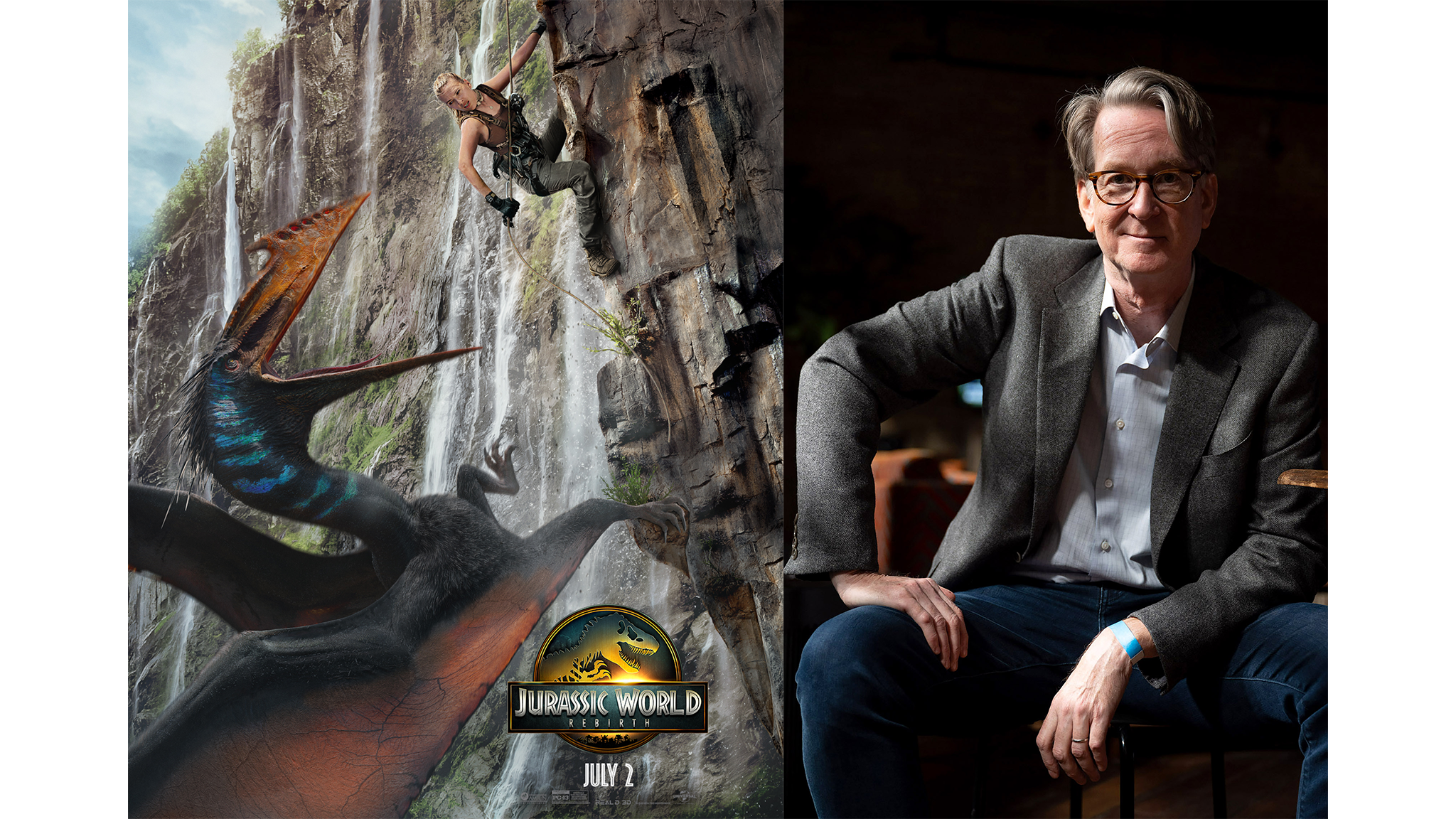

Ed Zwick is one of the few writers, producers and directors in Hollywood to win both the Academy award and the Emmy. He’s been at the forefront of groundbreaking television series like “Thirtysomething” and “My So-Called Life” and has been behind the camera for legendary epics like, “Glory,” “Legends of the Fall,” and “The Last Samurai.”

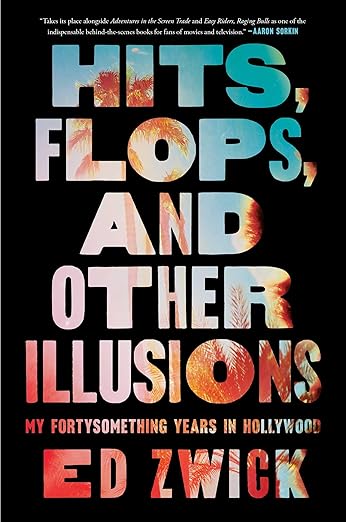

He’s worked with talents from multiple generations in his 40-year-plus career in show business. More importantly, he routinely gets the best out of all the actors he’s collaborated with. A meticulous notetaker his entire life, Zwick has now shared his most inspired, funny, sad and ultimately authentic stories from his career in his memoir, “Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions: My Fortysomething Years in Hollywood.” He sat down with Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA” to tell host, Doug Gordon, as much as he could about his literal book-length resume.

The following has been edited for clarity and for brevity.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Doug Gordon: Ed, you stepped into the world of Hollywood as a PA for Woody Allen. What was that like?

Ed Zwick: Well, I was 21 years old. I knew nothing about being on a set. All I knew was my absolute adoration of movies, but I never felt that that would be, available to me, because I’d never been that kid carrying around a Bolex and shooting little pieces of Super 8. I was a theater kid. I was always directing plays and working in the theater.

I had, through the most serendipitous of circumstances, encountered (Allen). I was in France, on a fellowship, and I happened to speak French, and he happened to be the only one there that spoke English. And I think that might have been the only reason why he invited me to come do it. He was exceedingly generous, just to a very presumptuous 21-year-old who asked the kind of questions I would never dare ask now. But, you know, there’s a certain kind of entitlement that you feel when you are that age and or at least ignorance.

What was remarkable to me is that he wasn’t a technocrat. He was a writer. And he surrounded himself with hugely talented cinematographers and designers and editors. And I realized that if you could be a writer and if you could articulate a vision that there may be people who could really help you realize that vision. So that inspired me. And rather than going back to the United States, to New York as I had planned, I went to California like everybody else who’s tried to reinvent themselves in their own image.

DG: You met Marshall Herskovitz when you both were in the American Film Institute directors program, and you described meeting him as a life-changing event. How so?

EZ: Well, you know, there are certain people that you encounter at different moments of your life that mark you. And those relationships didn’t happen to me in college. It just started to happen to me when I came here.

Obviously, it was based on admiration. He was hugely talented already. Way ahead of where I was. Very kind. We had a lot in common. We talked about our families. A lot of what the program had to do with was actually digging into some personal history and trying to apply that to the kind of film we wanted to make. And before we knew it, we were collaborators. And it’s been much more than that, though. I’m very proud of the work we’ve done together.

But what I’m proudest of, really, is this friendship has just grown, and it’s been as much about learning from each other.

DG: Would it be fair to describe it as kind of a brotherly relationship?

EZ: Definitely. Yeah. I have two wonderful sisters, but never had a brother. I certainly think of him as such.

DG: You and Marshall went on to create the hit TV series “Thirtysomething.” You were on your own dramatic rollercoaster in real life as well. How did you draw from those real-life experiences for the show?

EZ: Well, we had no choice. I mean, when you’re confronted by life, as it happens, when you have kids and we’re trying to run the television show, they inevitably blend — the issues of marriage, and ambition, and work and the pressures and the need for bonding with each other. It just all tended to become a blur.

In television at that moment, everybody was a doctor or a lawyer or a cop. That’s just not what we’re interested in. We’re interested in the smaller moments that aggregate into bigger moments. And so, we decided to narrow our focus and to try to find what was epic and what was emotional in the familiar. And the funny thing is, now that’s what television seems to do all the time.

DG: It was also around this time when you got a chance to direct the Civil War drama, “Glory.” You say that there was a moment rehearsing that marked the true beginning of your career as a director. Can you tell us a bit about that?

EZ: Yeah. I mean, I think when you start, you’re very concerned with control and over determining things with the actors. You’re so full of anxiety that it blinds you or clouds your vision. And I think when I saw what was happening with Denzel (Washington) and with Morgan (Freeman) and Andre (Braugher) and Jihmi (Kennedy), I realized that I was in the presence of something really extraordinary. And if I was smart, I would just shut up and let it happen.

DG: That’s very interesting. Thanks for sharing that. “Glory” features a powerful performance from Denzel Washington. He won an Oscar for his role. How did you two collaborate?

EZ: You know, that was the first of several movies that Denzel and I did together. So, we didn’t know each other well. And I wouldn’t say that there was great affinity yet. I think he takes his work very seriously and prepares. And yet the nature of the character that he was playing is very removed from everyone else in that group. And he very much kept to himself during the shooting of it.

Our friendship really began pretty much after that. In success there’s an opportunity to have a bit of a valedictory. And we traveled with the movie together. I actually remember we went to Berlin together. It was the week after the wall came down and it was so thrilling. We went to the East with the movie and it was the first American movie shown in the East, and it was a movie about people seeking their freedom. It was full of moments like that. And thereafter, our families got to know each other, and a real friendship developed.

DG: One of the most powerful scenes in “Glory,” if not the most powerful, is the whipping scene. And you write about that in the book — about how you worked with Denzel on that. Can you tell us that anecdote?

EZ: Well, I mean, we were in Savannah, Georgia. We were only miles from a place where Black men, as slaves, were kept in chains not long before. Historically, there were ghosts and everybody was aware of them. And Denzel was a spiritual man, and he was feeling that. And also the humiliation of standing there, being whipped by a white man in front of hundreds of other men was very difficult. And we did a take, and it was fine. I absolutely could have moved away, but I just felt there was something more.

But rather than talking to Denzel, I talked to John Finn, who was the guy with the whip. And it wasn’t a real whip. It was a piece of shammy attached to a stick, but nonetheless, it stung a little bit.

And all I said to him is, ‘John, this time just don’t stop ’till I say cut.’ And as it went past what Denzel was expecting, it became a very different experience where the control was taken away from him, as it would have been taken away from him in real life.

And I was sitting there next to the dolly grip, and I just waited for that moment when I sensed it happening, and I tapped him on the shoulder, and we pushed in and happened to get there right at that moment when that tear came down and it was magic. He knew. And he’s so smart. And even if he might have been angry that I was in some sense manipulative, he also knew that it was working. And that’s what a brilliant movie actor does. You can somehow, maintain those two realities at the same time.

DG: Yeah. And as you just mentioned, Denzel wasn’t mad at you for doing that, right?

EZ: No, I mean, there might have been some pique for a moment. But no. He’s just so intuitive and he has such a sense of what’s happening. And that takes extraordinary poise and confidence and concentration not to break and say, ‘What are you doing?’ It was actually a subordination of his ego at that moment.

DG: Yeah. Thank you for sharing that with us. Denzel would not be the last acting legend you would work with. Your next movie project was “Legends of the Fall,” with acting heavyweights Brad Pitt and Anthony Hopkins. What was your approach to working with them?

EZ: Well, they’re very different. I mean, Anthony Hopkins is a man from the National Theater, schooled in the classics, and Brad really worked his way up from Missouri without training to begin and he was very intuitive. And so, it was a little bit difficult sometimes finding that common ground.

The truth is that Sir Anthony Hopkins loves Westerns. And all he’d wanted his whole life was to be in a Western. And so I think actually it was his good nature that helped us find some sort of voice where it would all work together.

DG: Interesting. And you didn’t find out that Anthony was a fan of Westerns until you were shooting?

EZ: He was doing wardrobe, and he tried on the clothes. And I saw him sitting out in a field smoking this pipe, and I just went out to say, ‘What are you up to?’ And he goes, ‘This is the best moment of my career.’ He was just a happy camper.

DG: That’s great! While you were prepping “Legends of the Fall,” you helped launch another groundbreaking TV series, “My So-Called Life.” This show starred Claire Danes. However, she was only 14 at the time, and you said that her limited availability was a blessing in disguise. How so?

EZ: Claire was actually only 13 when we first met her, and nobody had ever done a show about teenagers with teenagers because there are labor laws.

Labor laws obliged you to have them in school certain number of hours, only to be able to work a certain number of hours. And we wanted her to be the star of the show.

So how could we do that?

And the answer was to expand our vision, to write stories that were much more substantive about the supporting characters, about her parents. And that then allowed us to put Claire in the center of things, but still, like, be in the center of a constellation or of a wheel. And she was the hub.

DG: You say that the only true way to measure the success of a movie is through time. So, if you applied that scale to “My So-Called Life,” how would it fare?

EZ: Well, I would say to you that every 35-year-old girl in America, every interesting 35 and 39-year-old girl in America was really moved by it. I can pretty much predict that that’s going to be a common theme. But the real thing is how it has continued. It still exists on Hulu, and there’s still people seeing it. We only shot 17 episodes over two years and yet has had this life of 30 years. I think because adolescence is one of those eternal evergreen stories.

DG: In 2010, you returned to the rom-com genre with “Love and Other Drugs.” It starred Anne Hathaway and Jake Gyllenhaal. You were going through a life crisis as you were making it. How did you deal with that?

EZ: How do you deal with it? Everything in life changes you. You know, love changes you. Good fortune changes you, and sickness changes you. And yet these all came together at the same time where I had just gone through a very serious illness at the time that I was making a movie, coincidentally, about someone going through a very serious illness.

It led to a certain gravitas, but it also was full of joy for me because I was better, and I was looking upon all of that opportunity as some kind of blessing. I felt like I was playing with house money. I’d never been so happy working. And that experience with them was great for that reason.

DG: You kept meticulous notebooks throughout your entire life, and that must have been very helpful in writing your memoir. I’m curious, though, what will your notebook next year say?

EZ: Wow. Well, I’m doing these kind of conversations. And, you know, writing the book posed interesting questions that I had to ask of myself. And then when I talk to people like this, I get asked other questions, and I’m hoping that it leads me into some other interesting creative place.

DG: What was the most interesting question you asked yourself?

EZ: Can I be authentic? Am I capable of looking at things with some objectivity? And can I be dispassionate about telling the truth about things? And sometimes that meant things that were hurtful, sometimes even things that were shameful. Sometimes it meant things that were self-glorifying. But I was just determined to see if I could do that and to the best of my ability. I tried.