Jake Rivard considers himself a free-speech absolutist. But in classes at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he sometimes feels compelled to censor himself when he thinks an instructor may not agree with his conservative views.

“I try not to do that and stand firm on my convictions,” Rivard said. “But there’s part of it, too, where is it really worth ruining my grade because I believe something slightly different than what the professor does?”

Rivard chairs the campus chapter of Young America’s Foundation, a conservative outreach group for college students headed by former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker. Last fall, he was one of more than 10,000 students who filled out a 29-page survey sent to UW System students aimed at gauging their feelings on free speech and the diversity of viewpoints at state campuses. The results show most students feel instructors encourage students to explore a wide range of viewpoints, though a majority of conservatives reported feeling pressured by an instructor to agree with a specific view in class.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

MGR Govindarajan understands that pressure, but for different reasons. The legislative affairs director for student group Associated Students of Madison said as a liberal growing up in a predominantly conservative part of the state, he too self-censored. He thinks concerns like Rivard’s might be more about social pressures from other students and campus culture than anything overt from instructors.

“I went to high school in Brookfield, Wisconsin,” Govindarajan said, in conservative Waukesha County. “And I found it hard to express my views in that pretty conservative school. And it’s the exact opposite over here. As a liberal, I have a much easier time expressing my views.”

The university’s free speech survey was funded in part by UW-Stout’s Menard Center for the Study if Institutions and Innovations, which is named after conservative billionaire and GOP donor John Menard. It comes after years of criticism by Republican lawmakers who believe the UW System stifles conservative viewpoints.

And the survey was controversial from the outset. It was opposed by some chancellors and even spurred the resignation of UW-Whitewater interim Chancellor Jim Henderson, who told Wisconsin Public Radio at the time he couldn’t encourage anyone to apply for a chancellorship because trust between campus heads and UW System leadership “was not honored.”

Critics of the survey argued it was politically motivated. A Republican bill introduced in the State Assembly in late 2021 would have required an annual surveys of all students and employees within the UW System and Wisconsin Technical College System to gauge First Amendment knowledge, perceived political bias and whether campus culture promotes self-censorship.

UW System President Jay Rothman said the survey wasn’t about politics, but was aimed at learning where students stand on freedom of expression in hopes of fostering civil dialogue at state campuses.

The survey’s results, released last week, are likely to fuel partisan divides about the UW System ahead of this year’s state budget. The Republican chair of the state higher education committee, Rep. Dave Murphy, R-Greenville, went so far as to call some of the responses “scary.”

GOP criticism of the state’s public universities is far from new. At least part of the debate over free speech at UW System schools goes back to 2016, days after former Republican President Donald Trump was elected.

GOP ramped up pressure on university after 2016 disruptions

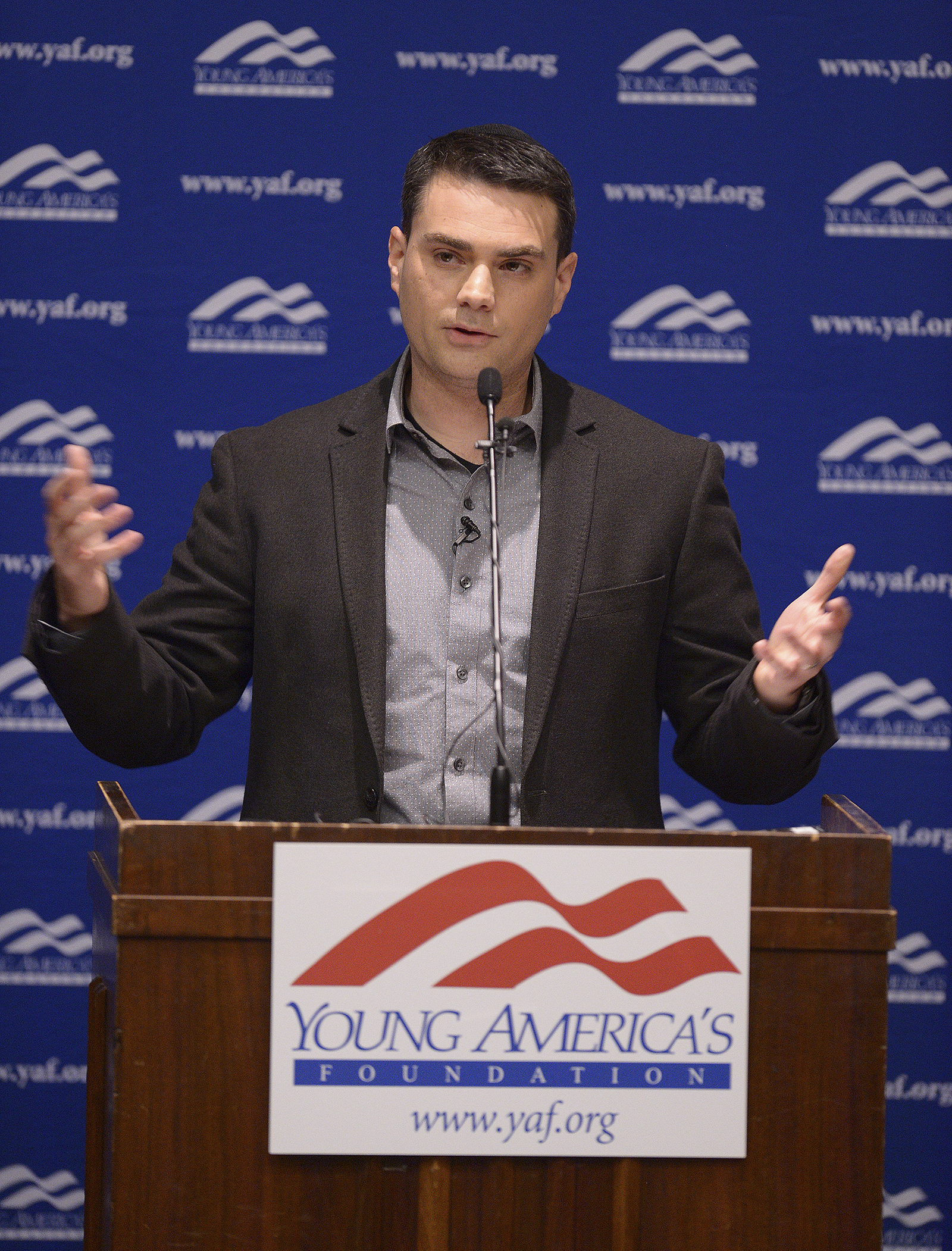

Less than a week after Trump was elected, nationally known conservative Ben Shapiro was at UW-Madison for a speech titled: “Dismantling Safe Spaces: Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings.” Shapiro hosts a national conservative radio talk show and owns The Daily Wire, one of the most popular right-wing websites on the internet. He’s also been widely criticized by liberals for arguing, among other things, that white privilege and institutional racism don’t exist. His appearance was organized by Young America’s Foundation.

Shapiro walked up to a podium in a crowded lecture hall amid thunderous applause and began his discussion by mocking a group of around 20 protesters in the room.

“I hear you started wearing these safety pins around because you want to show your fellow college students how you’re not one of these awful, terrible Trump people, that you’re sensitive, and you want to signal your virtue,” Shapiro said mockingly. “So I brought these safety pins just for you. And I brought along something to wear them with: this diaper.”

During the next 20 minutes, Shapiro’s speech was sporadically interrupted by members of the group, shouting things like “safety” and “shame.” He traded barbs with individual protesters as the group and others in the audience tried shouting over each other with cries of “safety!” and “shame!” drowned out by chants of “USA!” and “free speech matters!” Protesters walked to the front of the room and partially blocked Shapiro’s podium. He was flanked by private security and a campus police officer.

The disruption of the event would become a flashpoint in a national battle about free speech on campus.

Those issues are still alive on campus today. The recent free speech survey asked students to what extent they agree with the idea of campuses disinviting speakers they deem offensive. Around half of students agreed somewhat, quite a bit or a great deal. When broken down by political leanings, 58 percent of students identifying as very liberal felt strongly that offensive speakers should be disinvited, while more than 75 percent of those identifying as very conservative felt strongly that offensive speakers should be allowed on campus. Wide gulfs on that question also appeared when broken down by students’ gender, sexual orientation and field of study.

Former UW System President Ray Cross, who oversaw state universities at the time of Shapiro’s 2016 appearance, told WPR the incident triggered “an exposure of one of the flaws” in the UW System’s policies on speech and expression.

“We want people to be able to rent a room or schedule a room and have a speaker and for that speaker to be able to speak up without being interrupted,” Cross said.

Provoking outrage on college campuses was also used as a tool by some right-wing commentators to gain publicity. Just months after Shapiro’s appearance in Madison, right-wing performer Milo Yiannopoulos spoke at UW-Milwaukee, where he named a transgender student who previously protested a campus locker room policy while holding the student’s picture up to the crowd.

That led UW-Milwaukee Chancellor Mark Mone to issue a statement condemning Yiannopoulos for attacking the student, while reminding students the university is prohibited by law from restricting access to speakers based on their viewpoints.

Yiannopoulos would later be banned from multiple social media sites for inciting harassment. In 2016, he appeared at an event with white supremacists; in 2017, he resigned from his position with the right-wing news site Breitbart after he made comments condoning pedophilia.

The controversy over Shapiro being shouted down at UW-Madison got the attention of Republican state lawmakers in Wisconsin. In May 2017, GOP members of the Legislature introduced a bill directing the UW System to draft a new policy on free expression to include punishments up to expulsion for any student who disrupts the free speech rights of others on campus in two separate instances.

The bill was a copy of model legislation called the “Campus Free Speech Act” created by the Goldwater Institute at the University of Arizona. In an email to WPR, Stanley Kurtz, who drafted the document, said it was responding to a “proliferation of campus shout-downs and a failure of administrators to deal with them.”

“Legislation is necessary because universities have systematically failed to discipline speech disruptions, even when they have policies that provide for discipline,” Kurtz said.

The Wisconsin bill never became law, but during an Oct. 2017 meeting, the UW System Board of Regents members — most of whom were appointed by former GOP Gov. Scott Walker — created a new policy that reaffirmed the system’s commitment to free speech. It specified that protesters cannot interfere when invited speakers express views they reject or even loathe and included a slightly expanded range of punishments for students. Those include a one semester suspension for students who twice disrupt free expression and expulsion for anyone who disrupts another’s free speech three times during their academic career.

A statement from UW-Madison at the time said it would follow the regents’ direction despite believing the sanctions “unnecessarily take away the discretion of a campus.”

The only no vote from the board came from then-regent Tony Evers, who said the policy “will chill and suppress free speech,” not protect it. Evers went on to defeat Walker in the 2018 governor’s race and was reelected last November.

Student groups protested the policy change with some saying the Legislature and regents were injecting politics into higher education. Cross said it was impossible to avoid political influence at the time and said he’d had a number of conversations with legislators who were upset by campus reactions to right-wing speakers.

“We tried to balance that with reality because we felt we had an issue that we had to deal with and it was put to us rather acutely with the Ben Shapiro incident,” Cross said.

A 2022 “Annual Academic Freedom and Freedom of Expression Report” notes the punishment provisions included in the UW System’s current free expression policy “are not currently in force.” It further states that during the 2021-22 school year, two sanctions were issued for violations of speech and expression rights. A UW-Milwaukee student was placed on probation by the school for threatening someone from off-campus who was handing out religious materials. At UW-Stout, an employee was reprimanded for a workplace conduct violation.

Tests of campus free speech, then and now

The debate over what constitutes free speech and free expression on college campuses goes back much further than 2016. In 1981, UW-Madison approved the nation’s first university speech code, which threatened punishments for instructors accused of debasing a student on the basis of gender, race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation or disability, by way of comments, instructional materials or teaching techniques even if those weren’t directed at a specific student.

Emeritus UW-Madison professor and prolific author on First Amendment battles, Donald Downs, was a leader in the push to eliminate the code, which happened by a vote by the faculty senate in 1999. He argued it violated instructors’ free speech rights and academic freedom on campus.

Downs gives UW-Madison credit for being a leader on free speech and free expression policies, but is leery of current hate and bias reporting systems, which can be used to report students and instructors to administrators for using degrading language, epithets, slurs and microaggressions on campus. He believes the concept and practice could keep teachers from challenging students to think about other viewpoints.

“Even if you’re vindicated, you know, are you going to take the risk to say something that might have that happen again now that it’s already on your record?” Downs said.

Despite Downs’ concern, the UW System’s free speech survey found 42 percent of all respondents felt strongly that students should report instructors who say something they feel could cause harm.

In October, Young America’s Foundation invited nationally known conservative Matt Walsh to speak at UW-Madison. The presentation included a screening of Walsh’s film “What is a Woman,” which is highly critical of transgender individuals and gender reassignment surgeries, which Walsh has said should be outlawed.

Ahead of Walsh’s visit, someone vandalized the campus’s student union with spray-painted messages. The event was sold out and went off without a hitch, Rivard said. He said there were around 200 people who couldn’t get in.

“What it tells me on the surface is that people are interested at least to hear what he has to say, even if they don’t agree with everything,” Rivard said. “I don’t agree with everything that he says. But there’s a part of what he says that I can get behind and I can support.”

The day of Walsh’s appearance on campus, around 100 protesters gathered to condemn Walsh’s message and support the local trans community.

Among them was UW-Madison Ph.D. candidate and instructor Caitlin Benedetto, who is a member of the Madison Abortion and Reproductive Rights Coalition for Healthcare that helped organized the protest.

“Primarily, I was feeling concern for trans and non-binary students at UW,” Benedetto said. “Especially undergrad students not feeling safe and not feeling like they’re full members of the community if the university was sponsoring this event.”

The university did not directly sponsor the event, but Benedetto noted that annual fees paid by all students are allocated to student organizations on campus, including YAF. She said she’s also a strong supporter of free speech rights, but believes anti-trans rhetoric on the right can create real danger.

“(Walsh) is signaling and perhaps fomenting even more suspicion and even violence towards trans people, and especially trans women,” she said.

The tension between legitimate interests in protecting free speech and also protecting the safety of all students can make these debates complicated, said Joe Cohn, legislative and policy director at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. The nonprofit group has defended free speech rights on campus since 1999 and defended both conservatives and liberals in court.

Almost everyone supports the broad concept of free speech, said Cohn, but sometimes people have blinders about particular aspects of controversial speech. He said it’s vitally important for people to be “extraordinarily careful” and resist the urge to think they’re the ones who would set the line in the right place.

“And if we lose the ability to kind of grapple with the uncomfortable conversations, even the ugliness of some views that might be out there in the world, we’re going to have a much harder time as a society grappling with those issues when those students become the people in power,” Cohn said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.