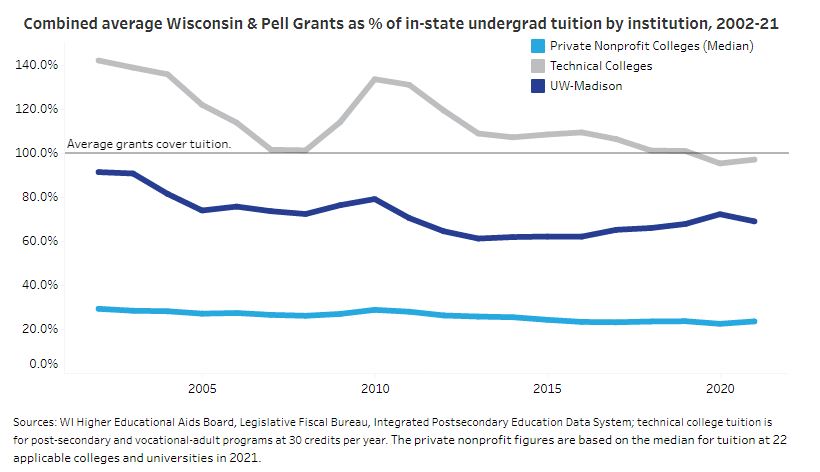

The amount of tuition costs at Wisconsin colleges covered by state and federal financial aid for students has shrunk over the last two decades, according to a new report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

The average amount of federal Pell grants and state Wisconsin grants together covered 91.4 percent of tuition at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2002, for example, but only 69 percent in 2021.

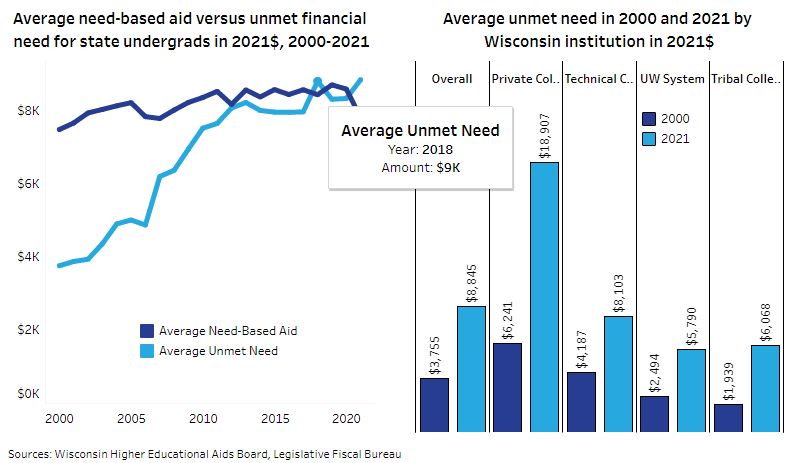

Students’ average unmet need, or the amount that remains after subtracting a family’s expected contribution and all the grants, loans, work study and scholarships they receive from total college attendance cost hit a new high of $8,845 in 2021.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“The buying power of the key need-based financial aid programs has diminished over time,” said Jason Stein, a researcher at the forum who authored the report. “And that doesn’t even count mandatory fees and textbooks and room and board, and all the other potential costs that a college student has.”

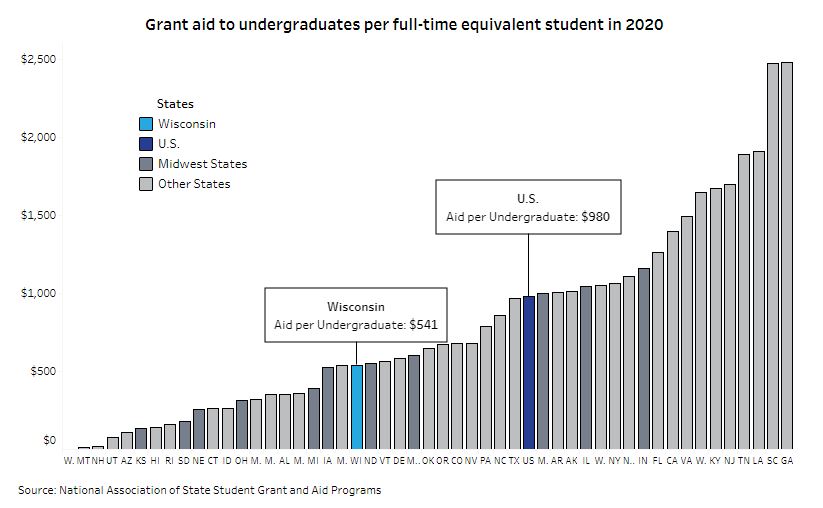

Wisconsin lags behind other states in how much the state spends per student on financial aid grants — $541 per undergraduate, almost half the $980 national average.

The burden of growing college costs and shrinking state and federal help falls heavily on students of color. The report found that 57.2 percent of Black students received federal Pell grants in 2018, compared to 28.2 percent of white students, so when those grants for students who have exceptional financial need can’t cover the costs of tuition and other college fees, they’re more likely to incur debt or have to drop out due to cost.

The high cost can have a snowball effect, Stein said.

“The less financial aid that a student has, the more likely he or she is to have to work to pay for their education, and the more they have to work, the less likely they are to take a full course load,” he said. “The smaller course load they have, the more time it’s going to take them to graduate and the more time it takes them to graduate, the more likely it is that something’s going to come up and they never do graduate.”

In some cases, universities and colleges can make up the difference between state and federal aid and students’ financial needs. The University of Wisconsin-Madison, for example, has Bucky’s Tuition Promise, which covers tuition for Wisconsin residents whose household income is $60,000 or less.

“Institutions, in some cases, have been able to step in to the gap, but the flip side of that is that not every institution has the financial wherewithal to be able to provide that kind of assistance,” said Stein.

In an emailed statement, UW System Interim President Michael Falbo said the state university network would like to see the program expanded to other system campuses.

“While students and families are picking up more of the costs of education, student aid has also fallen behind. Declining student aid increases student debt, depresses enrollment, and exacerbates Wisconsin’s workforce challenges,” he said. “That is why we proposed expanding UW-Madison’s Bucky’s Tuition Promise to all UW System universities in the last budget. Targeted aid to students will help more than just those students and families affected, it would help all of Wisconsin.”

Wisconsin legislators have tried to control some of the costs of higher education by freezing tuition at the UW System, but the report noted that that doesn’t help students at private and technical colleges.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.