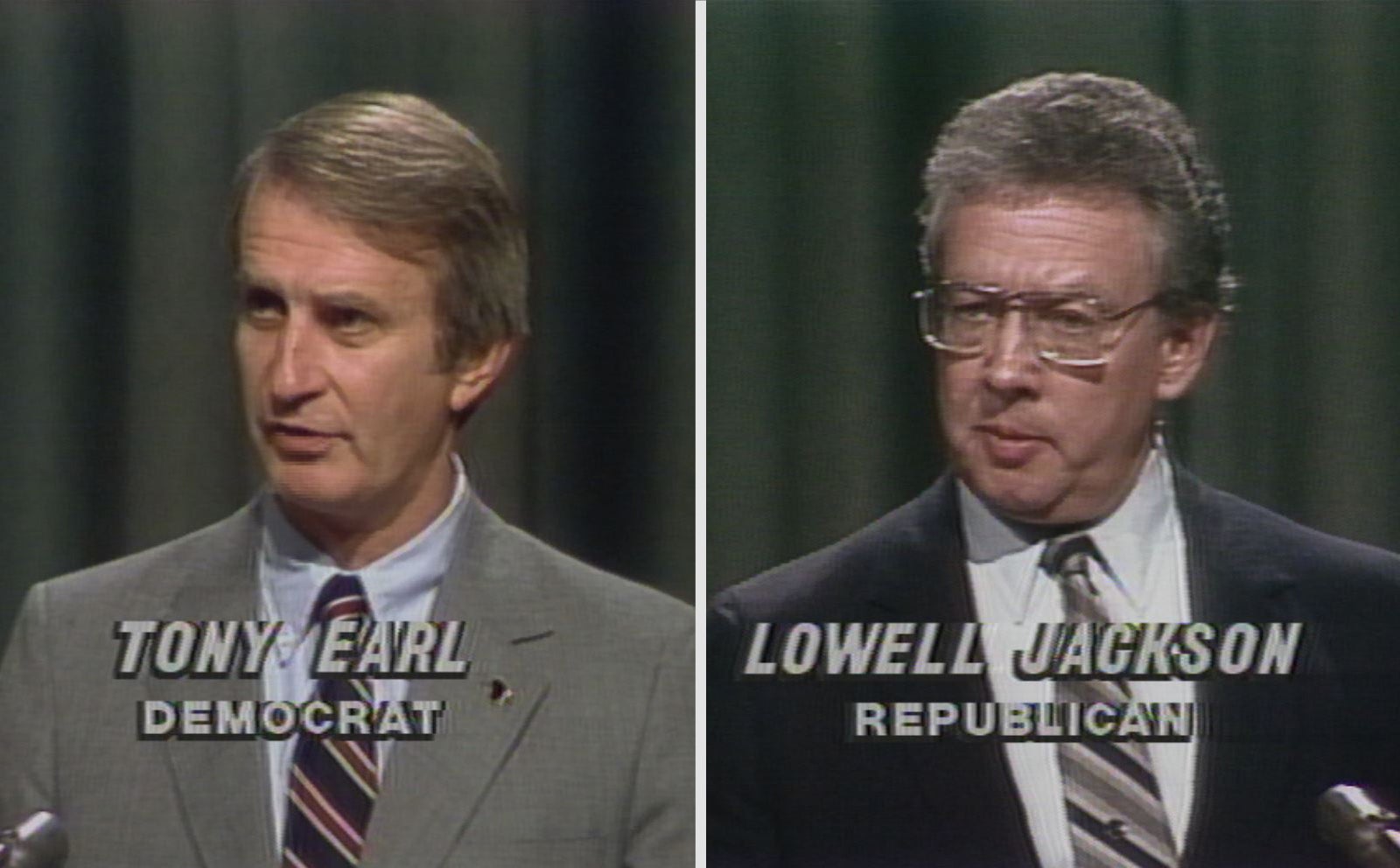

Democrat Tony Earl was an underdog in his party’s 1982 primary race for governor. Republican Lowell Jackson was an underdog, too.

Their shared situation gave them an idea for how to improve their political fortunes. In the process, Jackson convinced Earl of the need for a law that would help pay for road construction in Wisconsin for decades.

To hear Earl describe it, neither he nor Jackson could get their party frontrunners to debate, so the two underdogs took matters into their own hands. Earl and Jackson debated each other during primary season, and they came to respect one another. By the time they shared a stage with the rest of the candidates for governor on Aug. 30, 1982, Earl and Jackson sounded like old friends.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Tony Earl, you and I have debated so often that I just don’t know what to say about you except I think I’ve taught you too much,” said Jackson.

That included the automatic indexing of the gas tax.

Jackson was Wisconsin’s Department of Transportation secretary under Republican Gov. Lee Sherman Dreyfus, who was elected in 1978 and did not seek a second term.

When Dreyfus took office, Wisconsin’s gas tax was just 7 cents per gallon. Dreyfus, with Jackson at the helm of the DOT, increased the gas tax twice, nearly doubling it to 13 cents.

“This Republican administration and this candidate is not an advocate of the free lunch,” Jackson said during the 1982 debate. Jackson argued that previous Legislatures and governors had let the state’s transportation revenue base “wither” by leaving the gas tax untouched dating back to the mid-1960s.

Jackson, a civil engineer, wanted to do more, and he found a willing partner in Earl.

“He was the founder of indexing,” Earl said during an interview this year at a pub on the state Capitol square. “Lowell was full of a lot of good ideas. That was one of his best.”

Earl said the idea behind indexing was relatively simple: The cost of gasoline goes up and down while the need for road projects is constant. Legislators don’t like to vote for gas tax increases, so indexing tied them to inflation and they went up automatically.

“Most people never notice, so there was never a bellyache,” Earl said. “Whereas if you don’t have it indexed, when you need it, you’ve got to go and ask the Legislature for a tax increase and nobody likes to do that.”

Jackson lost the Republican primary for governor, but Earl won his Democratic primary. After he went on to defeat Republican Terry Kohler to win the 1982 governor’s race, Earl asked Jackson to stay on as his transportation secretary.

When Earl took office, Democrats held majorities in both the Wisconsin state Senate and Assembly. He said some Democrats were uneasy about Jackson’s indexing proposal, but when Earl put it in the budget, it passed.

“It was a ‘Republican’ issue, and the Democrats were willing to give me the benefit of the doubt,” Earl said. “That’s how it happened.”

Wisconsin’s gas tax was 16 cents per gallon when indexing began April 1, 1985. It lasted two decades before a different bipartisan coalition repealed the law in 2005, and when the last automatic adjustment took place April 1, 2006, it raised the gas tax to 30.9 cents per gallon, which is where it sits today.

If the law had remained on the books, it would have increased Wisconsin’s gas tax by another 6.5 cents per gallon by now, according to the nonpartisan state Legislative Fiscal Bureau. But its repeal has resulted in more than $1.2 billion in lost revenue for state government, which is one of the reasons the state is struggling to pay for roads today.

“I always thought (gas tax indexing) made perfect sense,” Earl said. “And I always thought it was a mistake to get rid of it.”

Construction Season In Wisconsin

Indexing automatically increased the gas tax twice during Earl’s single term as governor, and the same budget bill Earl used to create indexing also called for two additional gas tax increases.

But it was Wisconsin’s next governor, Republican Tommy Thompson, who saw the full benefits of the law.

“When I was governor, there was the joke that in Wisconsin there are two seasons: winter time and highway construction time,” Thompson said. “Because we were rebuilding highways all over the state.”

Thompson served 14 years as Wisconsin’s governor. He signed two gas tax increase into law, but the gas tax went up automatically through indexing 11 times. Indexing also reduced the gas tax twice, but the decreases were nominal.

When Thompson took office in 1987, Wisconsin’s gas tax was 17.5 cents per gallon. By the time he left office, it had gone up to 26.4 cents. The revenue helped Wisconsin build a grid of four-lane roads that connected the state.

“Indexing really allowed for us to grow our highways with gasoline taxes, and the Legislature didn’t have to deal with it,” Thompson said. “And it just opened up Wisconsin for business, for travel, for tourism and for job creation.”

Thompson, who was from the small town of Elroy, was most proud of road projects that improved State Highway 53 connecting La Crosse and Superior, and Highway 29, which runs from western Wisconsin to Green Bay through Wausau.

“It was really a love affair for me to rebuild Highway 29 and make that a four-lane highway,” Thompson said.

Thompson understands critics viewed indexing as taxation without representation.

“In theory, that’s very good,” Thompson said. “But the truth of the matter is nobody’s going to vote for a gasoline tax, and as a result of that, our highways are in bad shape. It was a tradeoff.”

A Bipartisan Unraveling

By 2005, Wisconsin was more polarized than in the days of Thompson or Earl. Even so, the state’s gas tax indexing law appeared to be safe.

Gov. Jim Doyle, a Democrat, was overseeing a massive reconstruction of the Marquette Interchange in Milwaukee. It was one of several expensive road projects in the works at Wisconsin’s DOT.

The Legislature, which was under Republican control, was run by Assembly Speaker John Gard and Senate Majority Leader Dale Schultz, who both supported indexing. Gard, who was from Peshtigo, spoke often of the need to fund Highway 41 in his district.

But many rank-and-file lawmakers wanted indexing repealed, with a handful of Democrats concerned it had created bloated budgets for highways and many more Republicans angry indexing was driving up taxes.

Those lawmakers had a powerful ally in conservative talk radio in Milwaukee. That was never more evident than when Gard took to the air to defend gas tax indexing.

“I understand the math of the budget,” Gard told WTMJ Radio’s Charlie Sykes in November 2005. “Outstate people who are counting on their communities for job growth and safe roads have a gun to their head right now if you simply just eliminate the index and don’t fix the transportation fund.”

Sykes cut Gard off. “Listen, I’m trying to help you out here because you’re kind of sounding like one of these guys who is going native,” Sykes said. “I’m trying to get you guys back on message.”

WISN Radio’s Mark Belling pushed back even harder when Gard made a similar pitch on his show.

“I believe you long-term devastate a lot of very badly needed infrastructure improvements around the state,” Gard warned Belling.

“Let’s test that,” Belling shouted back, catching Gard by surprise. “Let’s test it then.”

After that, it was hard for Gard, Schultz and the state’s powerful road-building lobby to contain the push to repeal gas tax indexing. There was talk that Republican Sen. Tom Reynolds, of West Allis, would force a vote on the bill whether leadership wanted it or not. Schultz relented, and Reynolds got his wish.

“Keep in mind, when we are voting, who are we voting for?” Reynolds said shortly before the state Senate vote to repeal indexing. “Are we voting for the special interests? Are we voting for our own special interests? Or are we voting for the interests of our constituents?”

Schultz, the Senate majority leader, had defended indexing to reporters just a day earlier, but he also voted to repeal Wisconsin’s gas tax indexing law.

“You know what?” Schultz said in a speech on the Senate floor. “We have the privilege and the right before we come here to change our mind.”

The state Assembly passed the repeal about a week later, sending it to Doyle’s desk with his re-election campaign just around the corner. A law born out of a bipartisan partnership would be repealed by one – the state’s top Democrat signed the Republican bill to repeal indexing without fanfare.

“I don’t think we can get by with less,” Doyle said in 2005 when he announced his decision to sign the repeal. “I think the Legislature is now itself on the hot spot, and that’s probably where they deserve to be. If they want to have those projects, and if the result is that they have to increase the gas tax, then they’re going to have to do it in straightforward way and take that vote.”

Three years later in 2008, with his re-election bid behind him and Democratic majorities in the Legislature, Doyle said it was time for the state to bring back gas tax indexing. That never happened.

Borrowing Instead Of Taxing

After the repeal of indexing, lawmakers never voted to increase the gas tax on their own. Until recently, legislators and governors never really stopped building roads, either.

But instead of taxing for roads, the state has borrowed more, a trend that escalated under Republican Gov. Scott Walker. When Walker took office, 11.5 cents of every dollar of transportation revenue went toward paying off old debt. By last year, that had climbed to 18.2 cents, and a recent projection showed it could grow to almost 23 cents two years from now.

Gard, who now lobbies for clients including road builders, wishes the indexing vote had gone differently.

“Ultimately, there’s a lot of responsibility on me from that,” Gard said in an interview last week. “There’s a tremendous investment that’s gone on and a significant chunk of it’s been borrowed money. And I don’t believe it’s a conservative principle to dump costs on our kids and grandkids.”

Schultz, who fell out of favor with many Republicans later in his career, has also left the state Legislature. He said the repeal of indexing was symptomatic of a larger phenomenon in politics that continues today.

“We have so-called conservatives who have forgotten the role of conserving the assets that we have and are now just anti-tax,” Schultz said.

Today, Democrats talk about bringing back indexing, while the Legislature’s new GOP leaders — Assembly Speaker Robin Vos and Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald — were among those who voted to repeal the law in 2005. Walker has taken a hard-line stance against any new taxes.

Tony Earl in 2017. Shawn Johnson/WPR

Lowell Jackson, the Republican transportation secretary credited by former Democratic Gov. Tony Earl as the “founder” of Wisconsin’s gas tax indexing law, died in 2006.

Earl, who is now 80, said he tries not to second-guess today’s political leaders.

“I had my kick at the cat,” Earl said. “Nobody gives a darn what I say anymore.”

But Earl makes an exception when it comes to indexing.

“I think they should have indexing,” Earl said. “No ifs, ands or buts.”

John K. Wilson contributed data visualization to this story.

This story is part of a WPR series on transportation funding that explores how we got here and what happens next.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.