The U.S. Department of the Interior is requesting public input on new names for more than 650 geographic features with racially offensive names — 28 of those sites are in Wisconsin.

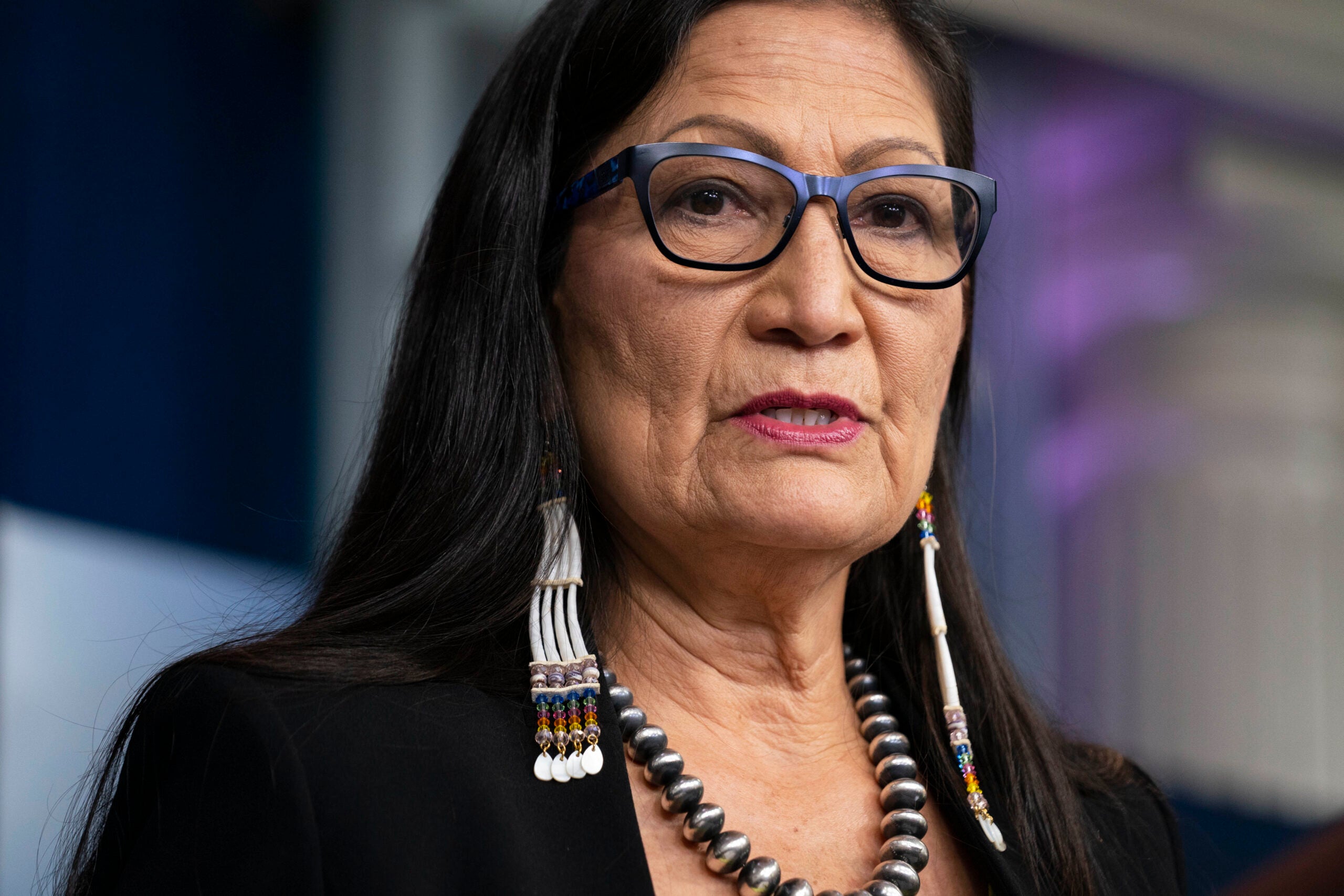

In November, DOI Secretary Deb Haaland signed Secretarial Order 3404 declaring a word that originated as an Algonquin term for “woman” a derogatory name. Its meaning has shifted after centuries of use by white people as an offensive term for Indigenous women.

Melissa Doud, a program director with the Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council and a member of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, supports the order.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“It’s such a derogatory and negative thing to call a woman,” Doud said. “We’re resilient people, and it’s only fair to change the name to something that isn’t so racist.”

The federal order outlined steps for removing the term from federal and state lands, one of the steps included forming the Derogatory Geographic Names Task Force.

By March, the task force identified 664 geographical features — such as creeks, lakes, rivers and valleys — across the country that use the term and proposed five new names for each site. The complete list of places and their suggested new names are available as both a PDF and an interactive map.

The 28 sites in Wisconsin span 19 counties.

The federal government will manage the process, but the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources is helping to solicit input and will review proposed names to avoid duplicating the names of nearby geographic features.

While the DNR has its own council to handle geographic name changes, DNR Statewide Tribal Liaison Kris Goodwill said the process can be lengthy.

“That process can easily take over a year to get that accomplished. This kind of puts it on a fast track,” Goodwill said.

Under the new order, sites with the word in their title would bypass the state process.

But even before the order, many Wisconsin counties were already trying to eliminate the term.

In 2019, Dane County changed the name of a bay on Monona Lake to Wicawak, the Ho-Chunk word for muskrat. And last year, a lake in Oneida and Vilas counties near the Lac du Flambeau reservation was changed to Amber Lake.

John D. Johnson Sr., president of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, said the old name was a dishonor to Native women.

“Here in Lac du Flambeau — and I can speak for other reservations too — we put our women on a pedestal,” Johnson said. “We appreciate everything they do for us, because if it wasn’t for the woman, none of us would be here, right?”

People had been trying to change the name for more than 20 years, but nothing ever happened, Johnson said.

Then in 2020, a tribal member who happened to live on what is now Amber Lake approached Johnson about changing the name. They encountered some pushback from local residents, but Johnson said collaboration between the tribe and the lake’s association was key.

“What we did with the Lakes Association was pretty cool because they had come right to our (Tribal) Council room and we had talked together, we collaborated and that’s what needed to be done,” Johnson said.

Together they submitted a formal petition to the Wisconsin Geographic Names Council and about six months later, residents and tribal members had collectively renamed the lake Amber Lake.

Doud said they initially chose the name Ikwe, which means “woman” in Ojibwe, but some residents felt it might be difficult to pronounce. Together they agreed on Amber because of the golden color of the Tamarack trees that surround the lake.

Now communities will have the backing of the federal government to speed up the process. And the movement to remove offensive terms from geographic features will not stop with this one word.

In November, Haaland also signed Secretarial Order 3405, creating a federal advisory committee that will identify and recommend new names for sites that use other racial slurs and derogatory terms. In the past, similar bodies have renamed geographic features that used the N-word or a pejorative term for Japanese people.

The committee has yet to be formed, but Goodwill said it could consider renaming features such as a rapid on the Tomahawk River that has a name that uses a derogatory term for someone who is of mixed race.

“This is a good move for the future. I think it’s overdue,” said Goodwill, who is a member of the Menominee Nation. “I think it goes along with having our first Native American secretary of the Interior.”

Public input on the current list will be accepted until April 25. You can submit comments online, using the docket number DOI-2022-0001. You can also mail your written comments to: Reconciliation of Derogatory Geographic Names, MS-511, U.S. Geological Survey, 12201 Sunrise Valley Dr., Reston, VA 20192. Be sure to include the docket number.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.