Efforts to develop sustainable fuels as an alternative to gasoline, diesel and other petroleum-derived products are receiving renewed federal support at a University of Wisconsin-based research center.

The U.S. Department of Energy renewed federal funding for the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center at UW-Madison for another five years. On Friday, the federal agency announced the four bioenergy research centers it supports, including Madison, will receive $590 million during that time span.

The Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center could receive up to $147.5 million over five years depending on the availability of funding from Congress. It is receiving $27.5 million out of $110 million awarded this year. With the award, the center has received more than $410 million. That makes it the university’s largest federally-funded project, according to the center.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

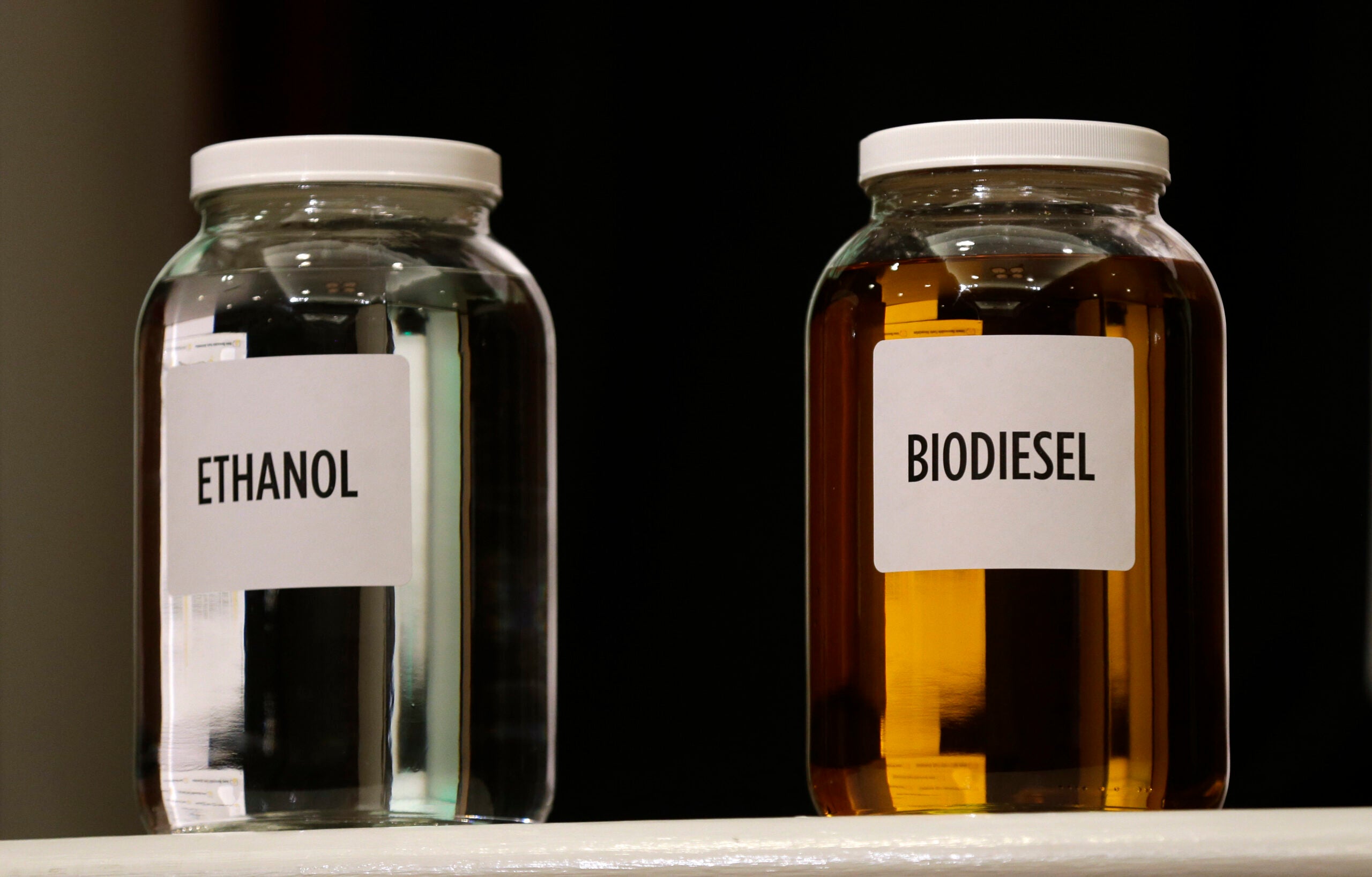

Photo by James Runde / Wisconsin Energy Institute

“This funding is going to go towards moving society closer to being able to make lower-carbon transportation fuels and chemicals using non-food crop material,” said Tim Donohue, the center’s director.

Donohue said they’re working with a renewable resource from plants known as lignocellulosic biomass. Lignocellulose is considered the most abundant biological plant material on the planet, with trees and grasses like poplar and switchgrass the major sources of the material. It contains large amounts of sugars and aromatic compounds, such as benzene, that can be used to make biofuels.

The transition to cleaner fuel sources is a key strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the transportation sector by 2050 under a national plan released in January. Transportation accounts for the largest share of the heat-trapping emissions that contribute to climate change.

“To meet our future energy needs, we will need versatile renewables like bioenergy as a low-carbon fuel for some parts of our transportation sector,” U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer M. Granholm said in a news release. “Continuing to fund the important scientific work conducted at our Bioenergy Research Centers is critical to ensuring these sustainable resources can be an efficient and affordable part of our clean energy future.”

Donohue said the centers are examining where to grow energy crops of non-edible plant material across the country without interfering with food production. He said researchers deconstruct the plant material into what he referred to as juices, likening the process to making wine or beer. It’s currently hard to break apart and that poses a barrier to cost-effective production of biofuels.

“We have learned how to make crops easier to dissolve into these juices, and we’ve learned how to make products like fuels and chemicals from as much of a ton of biomass as possible,” Donohue said.

The center has been engineering microbes that can convert energy crops like switchgrass to fuel at the lowest cost. Donohue said they’re also making great strides in understanding the interaction of plants and roots underground and their ability to store carbon as it relates to their chemical properties. He said researchers are trying to determine how those properties change during different seasons, which will help industries that convert them into fuels or chemicals.

The center also examines where refineries may be sited to produce biofuels within 50 to 75 miles from locally grown crop material.

“That means local rural communities that are a source of this material would be the ones that would benefit from new jobs and new industries being rolled out in those areas that have typically not been producers of the fuels and chemicals that we’re talking about,” he said.

The center is also working on ways to convert as much plant material as possible into chemicals needed for making biodegradable plastics and replacements for polyesters or lubricants.

U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin said the investment will support Wisconsin research efforts to cut energy costs and address climate change.

“These resources will help Wisconsin’s research institutions continue to innovate, boosting farmers’ and producers’ bottom lines, developing cleaner energy, and moving our Made in Wisconsin economy forward,” Baldwin said in a release.

Donohue said the state, which imports fuels and chemicals from elsewhere, could position itself to use locally grown biomass to make those products in Wisconsin.

Established in 2007, the center collaborates with Michigan State University and other partners. It employs more than 450 researchers, students and staff. Since its inception, the center states its partnerships have produced 1,700 scientific papers, 260 patent applications, 113 licenses or options and five startup companies.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.